List of paintings

The Franciscan Friars Minor probably arrived in Koper at the beginning of the second half of the 13th century. Their church was erected shortly after 1265.[1] In the second half of the 16th century, the monastery complex was the seat of the Holy Inquisition for the territory of Istria,[2] while the monastery continued to function until Napoleon’s occupation of this region in 1806.[3] After the monastery’s dissolution, the building was used as a military barracks. In the middle of the century, a primary school moved in,[4] while in 1875, a trilingual teachers’ college (Istituto Magistrale) started using the facilities and remained there until 1923,[5] when the complex was once again assigned to the military.[6] In 1940, the monastery briefly housed the Ente Nazionale di Educazione Marinara, a higher primary school,[7] while after World War II – in 1958 – it became home to the Slovenian Teachers’ College, which was transformed into a grammar school (so-called gimnazija, a general upper secondary school) in 1969. The latter still resides in the building today.[8] The church building had a different fate. In June 1833, the Domain Office granted the church, free of charge, to the municipality of Koper.[9] In 1857, the city bought the church to use it as a gendarmerie barracks.[10] In 1872, the church building was used as a stable and a warehouse,[11] while in 1879, it was a school gym for all the city schools.[12] In 1910, the church interior was used for an exhibition of agricultural machinery as part of the First Istrian Provincial Exhibition.[13] Meanwhile, it retained its function as a gym both during the Italian rule and in the post-war period until 1991.[14] The church was restored to its present appearance following the conservation and restoration works between 2012 and 2013, during which its medieval appearance was partially restored.[15] After the renovation, it was given the function of a protocol and event hall.

________________________________________

[1] For more details about the arrival of the Franciscan Friars Minor and the church’s architectural history, see: OTER GORENČIČ 2012, pp. 555–588 (with earlier bibliography).

[2] For more information about the Inquisition, see especially MARAČIĆ 2001 a, pp. 168–171.

[3] About the monastery’s dissolution, its fate and assets at the time, see especially BONIN 2004, pp. 109–120.

[4] ČEBRON LIPOVEC 2012, p. 516.

[5] BONIN 2004, pp. 119–120.

[6] CHERINI 1996, p. 7.

[7] CHERINI 1996, p. 7.

[8] Cf. BONIN 2004, p. 120; ČEBRON LIPOVEC 2012, p. 517.

[9] At the same time, measurements were taken of the entire church area. The church had four chapels (three on one side and one on the other), six windows, and an entrance doorway made of worked stone. The original document is kept at the Koper Regional Archives, Koper 12, container 100, item 149. Quoted after BONIN 2004, p. 119.

[10] BONIN 2004, p. 119.

[11] BONIN 2004, p. 119.

[12] Cf. BONIN 2004, p. 119; ČEBRON LIPOVEC 2012, p. 517.

[13] Cf. Prima esposizione 2010, pp. 118–121, figg. 38, 39.

[14] ČEBRON LIPOVEC 2012, p. 517.

[15] Cf. HOFMAN 2016, pp. 95–97; KOŠUTA 2016, pp. 97–98. The technical foundations for the renovation of the church were provided by ŠTEFANAC 2013. The 2010 conservation plan for the restoration, the report on the analysis of the paint layers of the uncovered murals, and the report on the natural scientific research are kept at the Restoration Centre Ljubljana, which also carried out the works.

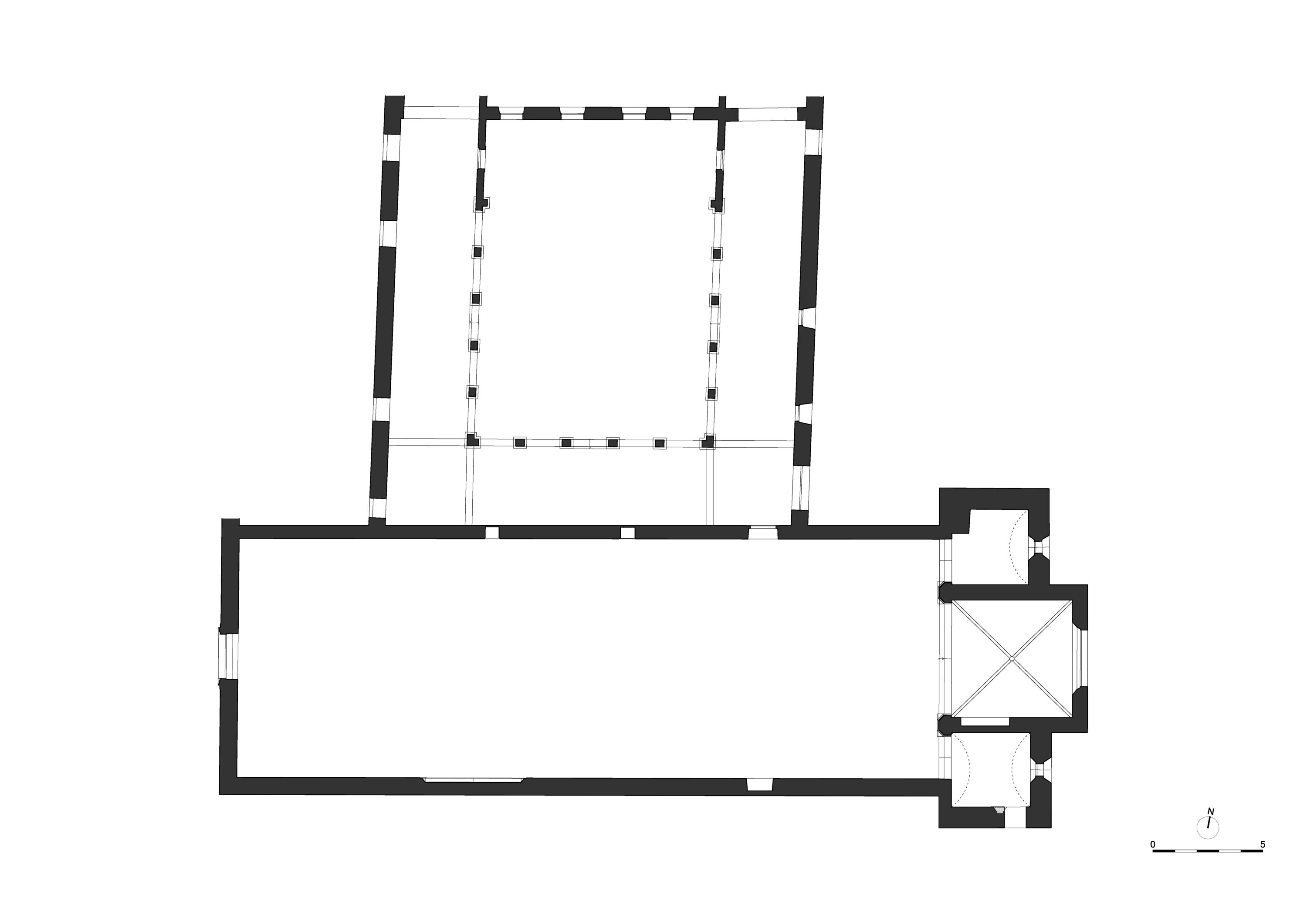

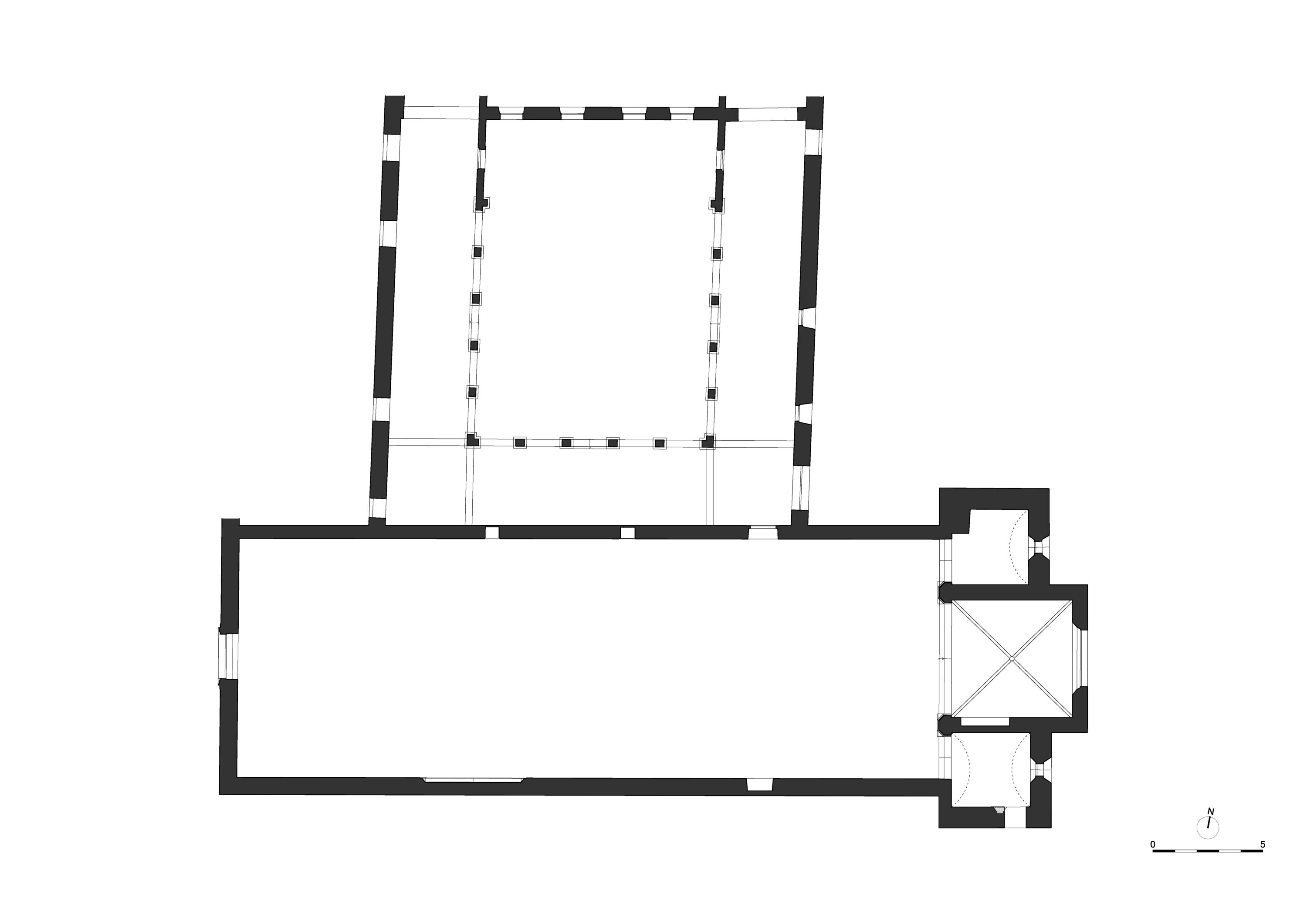

The church features a medieval architectural design with a single nave and three choir chapels with rectangular termination, whose total width exceeds that of the nave.[1] The original nave had an open roof structure.[2] However, in the Middle Ages, a side chapel with polygonal termination was probably added on the southern side of the nave, and its entrance arch has been preserved on the nave wall.[3] The medieval church was reconstructed in the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries. In the middle of the 18th century, it was first Baroquised. At that time, the façade was renovated (two windows were opened, and a new entrance door was made); the Gothic windows in the nave walls were replaced and lowered; a new marble altar of the Immaculate Conception was installed inside;[4] the church ceiling, painted by Giuseppe Camerata in the fresco technique, was repaired;[5] the interior walls were given a Marmorino look; the choir was restored; the “sanctuary” was decorated with frescoes;[6] the remaining altars were restored; the modest sacristy was renovated; new bells were bought; the pews in the church were modernised; in short, “all the necessary renovations were carried out”.[7] During the renovation of the façade and the opening of two new windows, an old rosette window in the western wall of the nave had to be walled up, although this is not explicitly mentioned in the sources. After the dissolution of the monastery in 1806 and the loss of its original function, the northern choir chapel, the vault of the southern choir chapel, and the side chapel on the southern wall of the nave were demolished, while a large semi-circular window in the chancel was opened instead of two smaller upright Gothic windows.[8] It had definitely been opened before 1910, when the church was used as an exhibition venue for an extensive Istrian exhibition with an entrance precisely through this window.[9] As it is evident from the preserved photographs, the northern choir chapel had already been demolished by that time.[10] The chapel with polygonal termination, which was added to the southern wall of the nave in the Middle Ages, was still standing in 1874, as indicated on the cadastral plan from that time.[11] However, it was no longer included in the plan of the church from the interwar period.[12] A water tower was built in its stead (or a bit further west), which was later assigned for use by the Koper Secondary School of Economics and Business.[13] The church was restored to its present appearance following the conservation and restoration works between 2012 and 2013, during which its medieval appearance was partially restored.[14]

The adaptations of the medieval monastery complex began in the second half of the 16th century when the seat of the Holy Inquisition for Istria was located there.[15] At that time, the Inquisitor had his own separate rooms in the monastery, which were supposedly more modern and comfortable than the older ones.[16] Alterations were also carried out in the 18th century. It is known that in 1711, the part of the monastery intended for the seminary was enlarged, while on 17 June 1755, the Chapter approved the heightening of the cloister wing, which faces the church, and the paving repairs in the nearby sacristy for the sake of better appearance.[17] In the 19th and 20th centuries, the monastery underwent the majority of alterations. During the time of Prefect Angelo Calafati, a major intervention was carried out during the rectification of what is today Cankarjeva ulica street, as a part of the monastery’s northern courtyard was demolished to make way for a new straight road.[18] The complex was also altered first in 1852 and then in 1914 to serve the needs of the primary school, which moved into the building in the middle of the 19th century.[19] In 1957, a new wing was added to connect the former monastery with the Vissich-Nardi Palace at Brolo square.[20] From 1965 to 1966, a major adaptation of the monastery’s interior was carried out under the leadership of the architect Zdravko Leskovic as the responsible building designer.[21]

________________________________________

[1] Such a floor plan type can only be found in the churches of the mendicant orders in Istria and could rightly be called the “Istrian type”. It is characterised by the absence of a transept and a wall niche in the eastern part of the nave, while the memory of the transept is preserved by three choir chapels, whose combined width exceeds that of the nave. With its architectural design, the Koper church (as well as the identically conceived but younger churches of the Franciscan Friars Minor in Pula and Piran) is part of the developmental line of the mendicant order architecture on the Apennine Peninsula and in the Adriatic region. For more information about this, see ŠTEFANAC 2013. All three chapels were originally rib-vaulted, but the original vault has only been preserved in the chancel. For more information about the church’s medieval appearance, see OTER GORENČIČ 2012, pp. 562–566.

[2] The Gothic decorative painted beams above the Baroque ceiling have been preserved; see KOVAČ 2000, p. 108.

[3] ŠTEFANAC 2013; see also OTER GORENČIČ 2012, p. 565, n. 35, who stated that the side chapel was dedicated to St Mary Magdalene.

[4] For information on the commissioning of the altar, see MARAČIĆ 2015, pp. 480–481.

[5] For more information about the fresco, see LUCCHESE 2001, pp. 83–85.

[6] The term “sanctuary” means the large chapel or chancel. I wish to thank DDr Janez Höfler for his comments.

[7] Inquisitor General Bernardino Fracchia da Valenza, who died in 1746, bequeathed almost his entire fortune to the monastery on the condition that he would be buried there, thus allowing its complete renovation. More about this in MARAČIĆ 2015, p. 482.

[8] See ŠTEFANAC 2013.

[9] Prima esposizione 2010, p. 119, fig. 38.

[10] Prima esposizione 2010, p. 119, fig. 38.

[11] JENKO 2014, p. 50; cf. BONIN 2004, p. 119.

[12] The sketch is kept in the Koper Regional Archives, Koper 6, item 39; published in JENKO 2014, p. 53. The chapel is also evident from the Franciscan cadastre for the Littoral region (1819). Furthermore, the contract of 1833, granting the municipality the use of the church, indicates that the church had four chapels. For more about this, see BONIN 2004, p. 119; cf. JENKO 2014, p. 50.

[13] Investicijski program. Protokolarno-prireditvena dvorana sv. Frančiška Asiškega v Kopru (sanacija sv. Frančiška), Maribor 2012 (realisation: Proplus inženiring, projektiranje d. o. o.).

[14] Cf. HOFMAN 2016, pp. 95–97; KOŠUTA 2016, pp. 97–98.

[15] MARAČIĆ 2001 a, pp. 168–171.

[16] NALDINI 1700, p. 192.

[17] MARAČIĆ 2015, pp. 478, 482.

[18] ČEBRON LIPOVEC 2012, p. 516.

[19] On the third floor, teachers’ apartments were built, while on the ground floor, a part of the grammar school was converted into a school for boys, according to the plans of the city architect Pietro Zeriul; see ČEBRON LIPOVEC 2012, p. 516, n. 25. In 1914, the monastery building was thoroughly renovated to improve the conditions of the teachers’ college (window enlargement, ground-level flooring repairs, electrification); see BONIN 2004, p. 119.

[20] ČEBRON LIPOVEC 2012, p. 516, n. 25.

[21] During the adaptation, all the wooden ceilings were replaced with reinforced concrete; the wooden floors and stone paving in the atrium and ground-floor corridors were removed; the partition walls were functionally rebuilt; and all the windows and doors were replaced. Furthermore, both stone staircases were removed, though the western one was of exceedingly high quality, made of white limestone worked by stonemasons. Its fragments were built into the balustrade in front of today’s courtyard entrance to the new extension. The main entrance was moved from the eastern to the western side, next to the former mortuary. The roof structure was also repaired, while the atrium was covered with translucent blue roofing on an iron structure; see ČEBRON LIPOVEC 2012, p. 517.

The Church of St Francis was included in the overview of the architecture of Slovenian coastal towns by Stane Bernik.[1] In the 1990s and early 20th century, its architectural history and conservation and restoration interventions were discussed mainly by Mojca MarjAna Kovač.[2] Later, Mija Oter Gorenčič focused on the medieval architectural heritage of the church,[3] while during the church’s last renovation, Samo Štefanac wrote about its preserved medieval elements and the starting points for its renovation.[4] New information about the history, adaptations, and various functions of the monastery and church in the 19th and 20th centuries has mainly been uncovered by Zdenka Bonin and Neža Čebron Lipovec,[5] while not long ago, Ljudevit Maračić also enriched our knowledge of the church’s Baroque appearance with information from preserved and previously unknown archival sources.[6] The church was also featured in the catalogue of the exhibition Gotika v Sloveniji, in the compendium Istria Città Maggiori, and in the catalogue Dioecesis Justinipolitana, dedicated to Koper art monuments.[7]

Antonio Alisi wrote about the discovery of the murals in the cloister during the interwar period,[8] while later, the frescoes were discussed in more detail by Janez Höfler in the second part of the collection Srednjeveške freske v Sloveniji, dedicated to the Littoral region, and in the catalogue Dioecesis Justinipolitana (2000).[9] Meanwhile, Alessandro Quinzi discussed them in the compendium Istria Città Maggiori.[10] In the latter, Enrico Lucchese discussed the Baroque ceiling fresco, painted by Giuseppe Camerata in the middle of the 18th century, in as many as three catalogue units.[11]

For historical information, we can refer to Paolo Naldini’s Corografia Ecclesiastica from 1700,[12] the older literature from the late 19th and early 20th centuries,[13] and the archival sources published by Antonio Sartori in 1986.[14] Lately, the history of the Franciscan Friars Minor in Istria has been the main focus of Anton Ljudevit Maračić.[15]

ALISI 1932

Antonio ALISI, Il Duomo di Capodistria, Roma 1932.

ALISI s. a.

Antonio ALISI, Il chiostro di San Francesco di Capodistria, Le ultime notizie. Il Piccolo delle ore diociotto, s. a. (a newspaper clipping kept at the Institute for the Protection of Cultural Heritage of Slovenia, Piran regional unit, without any information about the time of publication).

BERNIK 1968

Stane BERNIK, Organizem slovenskih obmorskih mest. Koper, Izola, Piran, Ljubljana-Piran 1968.

BONIN 2004

Zdenka BONIN, Pokopavanje v samostanski cerkvi manjših bratov konventualcev sv. Frančiška v Kopru med leti 1719 in 1806 ter razpustitev samostana, Arhivi, 27/1, 2004, pp. 109–120.

CAPRIN 1905

Giuseppe CAPRIN, L’Istria nobilissima, 1, Trieste 1905.

CHERINI 1996

Aldo CHERINI, Chiesa e convento di San Francesco a Capodistria, Trieste 1996.

CUSCITO 1982

Giuseppe CUSCITO, L’insediamento francescano in Istria. Lineamenti storiografici, Provincia Veneta dei Frati Minori e del Comitato Capodistriano per le celebrazioni. Beato Monaldo di Giustinopoli 1210–1280 ca, Trieste 1982, pp. 29–56.

ČEBRON LIPOVEC 2012

Neža ČEBRON LIPOVEC, Usode in nove rabe koprskih samostanov po razpustitvi redov s poudarkom na obdobju po drugi svetovni vojni, Annales. Series Historia et Sociologia, 22/2, 2012, pp. 509–522.

GRANIĆ 1887

Girolamo GRANIĆ, Album d’opere artistiche esistenti presso i minori conventuali della antica provincia Dalmato-Istriana ora aggregata alla patavina di S. Antonio, Trieste 1887.

GUČEK 1995

Mojca GUČEK, Samostanski kompleks in cerkev sv. Frančiška od nastanka do današnjih dni, 50 let Gimnazije Koper 1945–1955. Zbornik ob 50-letnici obnove slovenskega šolstva v Slovenski Istri (ed. Jože Hočevar), Koper 1995, pp. 35–39.

GUČEK, ŠTEFANAC 1995

Mojca GUČEK, Samo ŠTEFANAC, Koper (Capodistria). Nekd. frančiškanska c. sv. Frančiška, Gotika v Sloveniji (ed. Janez Höfler), Narodna galerija, Ljubljana 1995, p. 49.

GUTMAN LEVSTIK, MLADENOVIČ, KRIŽNAR, KRAMAR 2019

Maja GUTMAN LEVSTIK, Ajda MLADENOVIČ, Anabelle KRIŽNAR, Sabina KRAMAR, A Raman Microspetroscopy-Based Comparison of Pigments Applied in Two Gothic Wall Paintings in Slovenia, Periodico di Mineralogia, 88, 2019, pp. 95–104.

HÖFLER 1997

Janez HÖFLER, Srednjeveške freske v Sloveniji. Primorska, Ljubljana 1997.

HÖFLER 2000

Janez HÖFLER, Mati Božja z Detetom med sv. Nazarijem in sv. Elijem, Dioecesis Iustinopolitana. Spomeniki gotske umetnosti na območju koprske škofije, Koper 2000, pp. 226–227.

HOFMAN 2016

Barbara HOFMAN, Koper – cerkev sv. Frančiška Asiškega, Varstvo spomenikov. Poročila, 50–51, 2016, pp. 95–97.

JENKO 2014

Ana JENKO, Opombe k srednjeveški arhitekturi beraških redov v Kopru, Zbornik za umetnostno zgodovino, n. s. 50, 2014, pp. 47–64.

KOŠUTA 2016

Katja KOŠUTA, Koper – cerkev sv. Frančiška Asiškega, Varstvo spomenikov. Poročila, 50–51, 2016, pp. 97–98.

KOVAČ 2000

Mojca MarjAna KOVAČ, Koper, nekdanja frančiškanska cerkev, Dioecesis Iustinopolitana. Spomeniki gotske umetnosti na območju koprske škofije, Koper 2000, pp. 107–108.

KOVAČ 2008

Mojca Marjana KOVAČ, Cerkev sv. Frančiška v Kopru. Umetnostnozgodovinske in arhitekturne raziskave v sklopu konservatorskega programa, Arhitekturna zgodovina (edd. Renata Novak Klemenčič, Martina Malešič, Matej Klemenčič), Ljubljana 2008, pp. 220–229.

LAVRIČ 1986

Ana LAVRIČ, Vizitacijsko poročilo Agostina Valiera o koprski škofiji iz leta 1579, Ljubljana 1986.

LUCCHESE 2001 a

Enrico LUCCHESE, 107. Ex chiesa di San Francesco, Istria. Città maggiori. Capodistria, Parenzo, Pirano, Pola. Opere d’arte dal Medioevo all’Ottocento (edd. Giuseppe Pavanello, Maria Walcher), Trieste 2001, p. 82.

LUCCHESE 2001 b

Enrico LUCCHESE, 109. Giuseppe Camerata 1676–1762, Istria. Città maggiori. Capodistria, Parenzo, Pirano, Pola. Opere d’arte dal Medioevo all’Ottocento (edd. Giuseppe Pavanello, Maria Walcher), Trieste 2001, pp. 83–85.

MARAČIĆ 1992

Anton Ljudevit MARAČIĆ, Franjevci konventualci u Istri, Pazin 1992.

MARAČIĆ 2001 a

Anton Ljudevit MARAČIĆ, Protureformacija u koparskoj biskupiji, Acta Histriae, 9/1, 2001, pp. 163–178.

MARAČIĆ 2001 b

Anton Ljudevit MARAČIĆ, Maleni i veliki. Franjevci konventualci u Istri, Zagreb 2001.

MARAČIĆ 2001 c

Anton Ljudevit MARAČIĆ, Franjevački počeci u Istri i samostan sv. Franje u Piranu, Sedem stoletij minoritskega samostana sv. Frančiška Asiškega v Piranu 1301–2001 (edd. France Martin Dolinar, Marjan Vogrin), Ljubljana 2001, pp. 23–39.

MARAČIĆ 2015

Anton Ljudevit MARAČIĆ, Convento di San Francesco a Capodistria. I verbali dei capitoli 1692–1806, Atti, 45, 2015, pp. 461–486.

MARAČIĆ 2019

Anton Ljudevit MARAČIĆ, Gli inventari della Custodia d’Istria della provincia dalmata di S. Girolamo tratti dal manoscritto “Libro della Custodia dell’Istria (1688–1739)”. Archivio del convento di S. Francesco in Cherso, Atti, 44/1, 2019, pp. 196–269.

MIKELN 1966

Tone MIKELN, Konservatorska poročila. Umetnostni in urbanistični spomeniki. Koper, Varstvo spomenikov, 11, 1966, pp. 148–149.

NALDINI 1700

Paolo NALDINI, Corografia ecclesiastica o’ sia Descrittione della citta, e della diocesi di Giustinopoli, detto volgarmente Capo d’ Istria, Venezia 1700.

OTER GORENČIČ 2012

Mija OTER GORENČIČ, Srednjeveška stavbna dediščina benediktincev, dominikancev, manjših bratov sv. Frančiška in klaris v slovenski Istri, Annales. Series Historia et Sociologia, 22/2, 2012, pp. 555–588.

PARENTIN 1982

Luigi PARENTIN, Il francescanesimo a Trieste e in Istria nel corso dei secoli, Trieste 1982.

PARENTIN 1988

Luigi PARENTIN, Ordini religiosi a Trieste e in Istria, Atti e Memorie della Società Istriana di Archeologia e Storia Patria, n. s. 36, 1988, pp. 77–96.

Prima esposizione 2010

Prima esposizione provinciale istriana – 100 anni/Prva istrska pokrajinska razstava – 100 let/Prva istarska pokrajinska izložba – 100 godina/Erste istrianische Landesausstellung – 100 Jahre (ed. Dean Krmac), Koper/Capodistria 2010.

PROHINAR 2008

Vanja PROHINAR, Koper, cerkev sv. Frančiška Asiškega, Varstvo spomenikov. Poročila, 44, 2008, pp. 99–101.

PUSTERLA 1891

Gedeone PUSTERLA, I rettori di Egida, Giustinopoli, Capo d’Istria. Cronologie elenchi, genealogie, note ed appendice, Capodistria 1891.

QUINZI 2001

Alessandro QUINZI, 108. Pittore attivo a Capoddistria, seconda mettà XIV secolo, Istria. Città maggiori. Capodistria, Parenzo, Pirano, Pola. Opere d’arte dal Medioevo all’Ottocento (edd. Giuseppe Pavanello, Maria Walcher), Trieste 2001, pp. 82–83.

SARTORI 1986

Antonio SARTORI, Archivio Sartori. Documenti di storia e arte francescana. La Provincia del Santo dei frati minori conventuali, 2/1, Padova 1986.

SEMI 1975

Francesco SEMI, Capris Iustantinopolis Capodistria, Trieste 1975.

ŠTEFANAC 2013

Samo ŠTEFANAC, Nekaj strokovnih izhodišč za prenovo minoritske cerkve v Kopru, Bilten SUZD, 22–23, 2013, http://www.suzd.si/bilten/arhiv/bilten-suzd-22-23-2013/374-spomenisko-varstvo/427-samo-stefanac-nekaj-strokovnih-izhodisc-za-prenovo-minoritske-cerkve-v-kopru.

VENTURINI 1906

Domenico VENTURINI, Guida storica di Capodistria, Capodistria 1906.

ŽELEZNIK 1959

Milan ŽELEZNIK, Konservatorska poročila. Umetnostni spomeniki. Koper, Varstvo spomenikov, 6, 1959, pp. 81–82.

ŽELEZNIK 1960

Milan ŽELEZNIK, Ob restavriranju fresk, Varstvo spomenikov, 7, 1960, pp. 72–88.

________________________________________

[1] BERNIK 1968, p. 8.

[2] Cf. GUČEK 1995, pp. 36, 38; GUČEK, ŠTEFANAC 1995, p. 49; KOVAČ 2000, pp. 107–108.

[3] OTER GORENČIČ 2012.

[4] ŠTEFANAC 2013.

[5] BONIN 2004; ČEBRON LIPOVEC 2012.

[6] Cf. MARAČIĆ 2015; MARAČIĆ 2019, pp. 196–269.

[7] Cf. GUČEK, ŠTEFANAC 1995; LUCCHESE 2001 a, p. 82; KOVAČ 2000.

[8] ALISI s. a.

[9] HÖFLER 1997, p. 99; HÖFLER 2000, pp. 226–227.

[10] QUINZI 2001, pp. 82–83.

[11] LUCCHESE 1999, pp. 83–85.

[12] NALDINI 1700, pp. 190–192.

[13] GRANIĆ 1887, p. 17; PUSTERLA 1891, p. 22; CAPRIN 1905, p. 34; VENTURINI 1906, pp. 81–82; ALISI 1932, p. 70; SEMI 1975, pp. 132, 135, 216, 396–397; CUSCITO 1982, p. 37; PARENTIN 1982, pp. 67–68; PARENTIN 1988, p. 87; CHERINI 1996.

[14] SARTORI 1986, pp. 397–402.

[15] MARAČIĆ 1992, pp. 76, 135–136; MARAČIĆ 2001 b; MARAČIĆ 2001 c, pp. 23–39.

The earliest information about the church and its furnishings comes from the 1579 visitation by Agostino Valier, the Bishop of Verona. At that time, the church had nine altars: the high altar and the altars of St Anthony, St Lucy, St Mary, St Mary Magdalene, St Sebastian, St Bernardino, Pietà, and St John the Baptist.[1] More detailed information on the history of the construction, a more precise description of the church, and an inventory of its furnishings were not provided until Paolo Naldini in his work Corografia Ecclesiastica in 1700.[2] The information collected from the relevant archival sources was published by Antonio Sartori in 1986,[3] while the two key works for the Baroque period are the manuscript books I Verbali dei Capitoli 1692–1806, kept in the archives of the Croatian Province of the Order of Friars Minor Conventual in Zagreb, and Libro della custodia, an inventory of the churches in the Dalmatian Province of St Jerome, kept in the archives of the Monastery of St Francis on the island of Cres. Both were reviewed by Ljudevit Anton Maračić, who also published the essential information.[4]

The more important visual sources that indicate the church’s layout include Giacomo Fino’s map of 1619,[5] the Franciscan cadastre,[6] and the cadastre of 1847,[7] while the photographs from the Istrian exhibition of 1910 reveal the appearance of the interior and the choir part of the church.[8]

________________________________________

[1] LAVRIČ 1986, pp. 70–71.

[2] NALDINI 1700. The visitation records of the friars of the Dalmatian Province of St Jerome, kept in the archives of the Franciscan Province of Zagreb, do not contribute to the reconstruction of the appearance of the church and its furnishings, as they mainly focus on spiritual reports.

[3] SARTORI 1986, pp. 397–402.

[4] MARAČIĆ 2015, pp. 461–486; MARAČIĆ 2019, pp. 196–269.

[5] Giacomo Fino’s drawing is preserved in the archive Archivio di Stato di Venezia, fonds Senato Mare, fol. 223.

[6] Archivio di Stato di Trieste, Franciscejski kataster za Primorsko, 1819.

[7] JENKO 2014, p. 50.

[8] Prima esposizione 2010, pp. 118–121, figg. 38, 39.

In 1852, the complex underwent minor alterations to meet the needs of the primary school that moved into the building in the mid-19th century, while in 1914, the monastery building was thoroughly renovated to improve the conditions for the teachers’ college (windows were enlarged, the ground-level flooring was repaired, and the building was electrified).[1] During the interwar period, when the monastery hosted the Naval College, extensive restoration and adaptation works were carried out under the direction of the Trieste Soprintendenza, including the removal of the 19th-century glass barriers, the uncovering of the frescoes in the cloister, the detachment of the more recent layer of frescoes in the lunette, and the removal of the tombstones from the cloister.[2] In 1957, a new wing was added, connecting the former monastery with the Vissich-Nardi Palace at Brolo square,[3] while from 1965 to 1966, a major adaptation of the monastery’s interior was carried out under the direction of the architect Zdravko Leskovic as the responsible building designer.[4] As part of these works, a niche with preserved Renaissance frescoes on the church’s façade was uncovered.[5] In the 1980s, the church received a new roof, while the gym was evicted in 1991 due to the endangerment of its users and the monument. Thus, the most urgent works were carried out in the same year and in 1992 to restore and present the preserved Baroque ceiling.[6] In 1994 – during architectural research and sampling in the chancel – the remains of subsequently rebuilt Gothic windows were discovered; a fragment of a fresco, of which only an arm remained visible, was found next to the large chancel window; while in the southern wall of the chancel, walled-up sedilia with exceedingly poorly preserved fragments of painted Gothic plasterwork behind them were uncovered.[7] In 2007, the research required for the preparation of a conservation programme for the comprehensive restoration and presentation of the church was carried out.[8] Pre-diagnostic surveys (ultrasound recordings, infrared thermography, GPR survey, and endoscopy) were carried out to establish an overview of damages and define the sampling fields. The first part of the research included sampling on the ground floor of the northern and southern nave walls, where the lower parts of all the Gothic window stone frames were discovered. On the southern wall, in addition to the Gothic window openings, a passage was found on the ground floor, presumably leading to the former side chapel.[9] While the sampling took place, sedilia with Gothic murals were uncovered in the southern chancel wall. The original Gothic passage from the nave to the cloister was revealed on the northern nave wall, while the presumably Baroque portal with a preserved lintel was walled up.[10] Due to the damage to the roof framework and waterlogging, the wooden roof and ceiling structure was re-inspected. An architectural survey of the existing condition with photographic documentation was also carried out.[11] As the works continued, the wooden ceiling structure was replaced with a new one,[12] and after the relevant research had been carried out, a plan for the complete renovation of the church was drawn up.[13] Further restoration and rehabilitation works began in September 2013. First, the ceiling was restored, after which the nave walls were renovated.[14] Simultaneously, works were carried out on two layers of murals discovered already in 2007 in a niche in the southern chancel wall. The top layer of the 15th-century mural was detached and transferred to the premises of the Restoration Centre, where it was restored and then installed on a special semi-circular construction on the northern chancel wall in the Church of St Francis. The lower layer – a 14th-century fresco, restored in the meantime – remained in situ.[15] As a part of the last renovation, the northern choir chapel was also reconstructed.[16] After the works had been completed, the church was given the function of a protocol and event hall.

________________________________________

[1] ČEBRON LIPOVEC 2012, p. 516, n. 25; BONIN 2004, p. 119.

[2] CHERINI 1996, p. 7; ALISI s. a.

[3] ČEBRON LIPOVEC 2012, p. 516.

[4] During the adaptation, all the wooden ceilings were replaced with reinforced concrete; the wooden floors and stone paving in the atrium and ground-floor corridors were removed; the partition walls were functionally rebuilt; and all the windows and doors were replaced. Both stone staircases were removed, though the western one was of exceedingly high quality, made of white limestone worked by stonemasons. Its fragments were built into the balustrade in front of the today’s courtyard entrance to the new extension. The main entrance was moved from the eastern to the western side, next to the former mortuary. The roof structure was also repaired, while the atrium was covered with translucent blue roofing on an iron structure. Quoted after ČEBRON LIPOVEC 2012, p. 517, n. 27.

[5] MIKELN 1966, p. 148.

[6] Mojca GUČEK, Poročila o konservatorskih delih na posameznih objektih kulturne dediščine. Koper. Cerkev sv. Frančiška, Varstvo spomenikov, 34, 1992, p. 236; Mojca GUČEK, Poročila o konservatorskih delih na posameznih objektih kulturne dediščine. Koper. C. sv. Frančiška, Varstvo spomenikov, 35, 1995, p. 107; Cf. ČEBRON LIPOVEC 2012, p. 517.

[7] Cf. Mojca GUČEK, Koper. Cerkev sv. Frančiška, Varstvo spomenikov. Poročila, 37, 1998, p. 48; KOVAČ 2000, p. 108.

[8] The basic review article about the course and results of the research up to 2008 was written by Mojca Marjana Kovač; KOVAČ 2008, pp. 220–229.

[9] Cf. PROHINAR, pp. 100–101.

[10] Cf. PROHINAR 2008, pp. 100–101.

[11] Mojca MarjAna KOVAČ, Koper – cerkev sv. Frančiška Asiškega, Varstvo spomenikov. Poročila, 44, 2008, pp. 101–102.

[12] Mojca MarjAna KOVAČ, Koper – cerkev sv. Frančiška Asiškega, Varstvo spomenikov. Poročila, 45, 2009, pp. 87–88.

[13] About the findings of conservation research until 2008, see KOVAČ 2008. The 2010 conservation plan is kept at the Restoration Centre Ljubljana, which managed the restoration works.

[14] HOFMAN 2016, pp. 95–96.

[15] KOŠUTA 2016, pp. 97–98.

[16] For more information about the works during the last restoration, see Konservatorsko-restavratorski projekt. Koper – Cerkev sv. Frančiška Asiškega, Ljubljana 2010; the typescript is kept at the Restoration Centre Ljubljana.

Legal Terms of Use

© 2025 ZRC SAZU UIFS, Corpus picturarum muralium medii aevi

ZRC SAZU

France Stele Institute of Art History

Novi trg 2

1000 Ljubljana

Spodaj seznam podrobno opisuje piškotke, ki se uporabljajo na našem spletnem mestu.

| Cookie | Type | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| _ga | Non-Necessary | 2 years | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. The cookie is used to calculate visitor, session, camapign data and keep track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookies store information anonymously and assigns a randoly generated number to identify unique visitors. |

| _gat | Non-Necessary | 1 minute | Google uses this cookie to distinguish users. |

| _gid | Non-Necessary | 1 day | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. The cookie is used to store information of how visitors use a website and helps in creating an analytics report of how the wbsite is doing. The data collected including the number visitors, the source where they have come from, and the pages viisted in an anonymous form. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | Necessary | 1 year | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-non-necessary | Necessary | 1 year | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Non Necessary". |

| CookieLawInfoConsent | Necessary | 1 year | The cookie is used to store the summary of the consent given for cookie usage. It does not store any personal data. |

| PHPSESSID | session | Time of session | Cookie stores information about the user's session and allow users to keep their entries during the time of visiting the website. |

| pll_language | Necessary | 1 year | This cookie is used to remember any selection a user has made about language. |

| show_preloader_once | Necessary | Session | With this cookie we remember the user's first visit. |

| viewed_cookie_policy | Necessary | 1 year | The cookie is used to store whether or not you have consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |