List of paintings

The church was first mentioned in 1425 when a certain property at the location of Erengruben pey Vnser frawn[1] was recorded in the Freising feudal book, and then in the Loka urbarium from 1500 as Ecclesia sancte Marie Erengrueben.[2] Later, the church of the Annunciation was also mentioned in two censuses of 1581 and 1667, the specifications of parish and vicariate incomes in 1684 and 1690, the visitation report and record of 1704 and 1752, and the census of 1783.[3] It was also included in the Glory of the Duchy of Carniola from 1689, in which Janez Vajkard Valvasor emphasised that it was a pilgrimage church and also mentioned the so-called giant maiden’s rib, whose origin he attributed to a whale or some other sea animal.[4]

Originally, this was a succursal church of the Stara Loka parish and did not belong to the Diocese of Freising but rather under the Loka dominion of the Diocese of Freising, while it belonged under the Patriarchate of Aquileia in ecclesiastical terms.[5]

________________________________________

[1] Historična topografija 2021, p. 158.

[2] HÖFLER 2017, p. 103; Historična topografija 2021, p. 158.

[3] For the exact titles of the works that mention the church, see the explanations of the years in the list of references in HÖFLER 2017.

[4] VALVASOR 1689, p. 726. The artefact is the rib of a whale hanging in the northern aisle on a remnant of a beam. In the local folklore, the rib was attributed to a giant woman who helped construct the church and perished in the process. For more details about this legend, see KOMAN 2000, pp. 35–36.

[5] Cf. HÖFLER 2017, p. 103.

The Crngrob church is one of the most prominent Slovenian art monuments. Its artistic image has been shaped over six centuries.[1] It was a renowned pilgrimage church, enlarged several times to accommodate the considerable number of pilgrims.[2] Today, thanks to all the reconstructions, it represents a notable document of the development of medieval architecture, while the preserved murals from the 14th and 15th centuries are crucial for understanding medieval mural painting in Slovenia.[3]

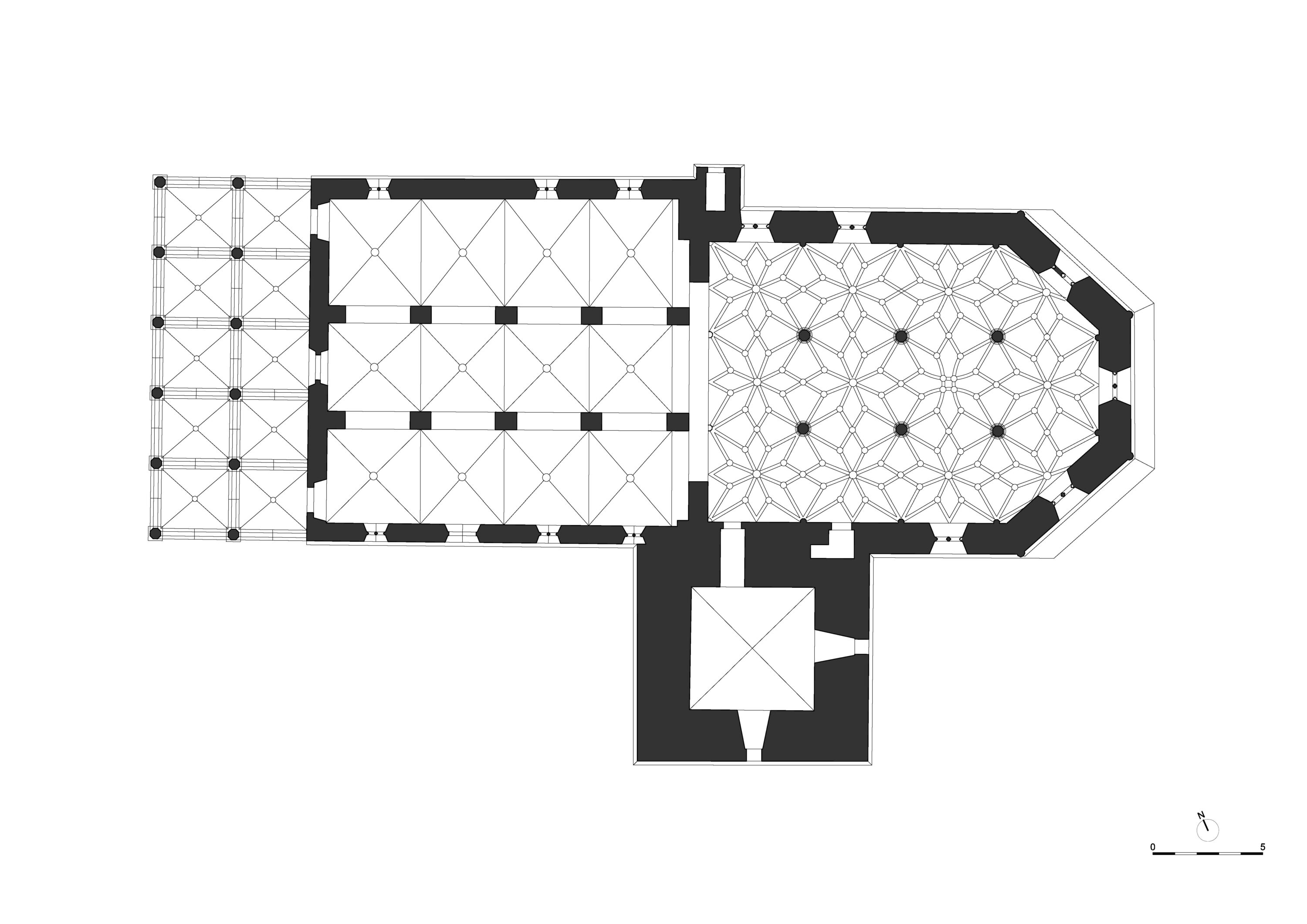

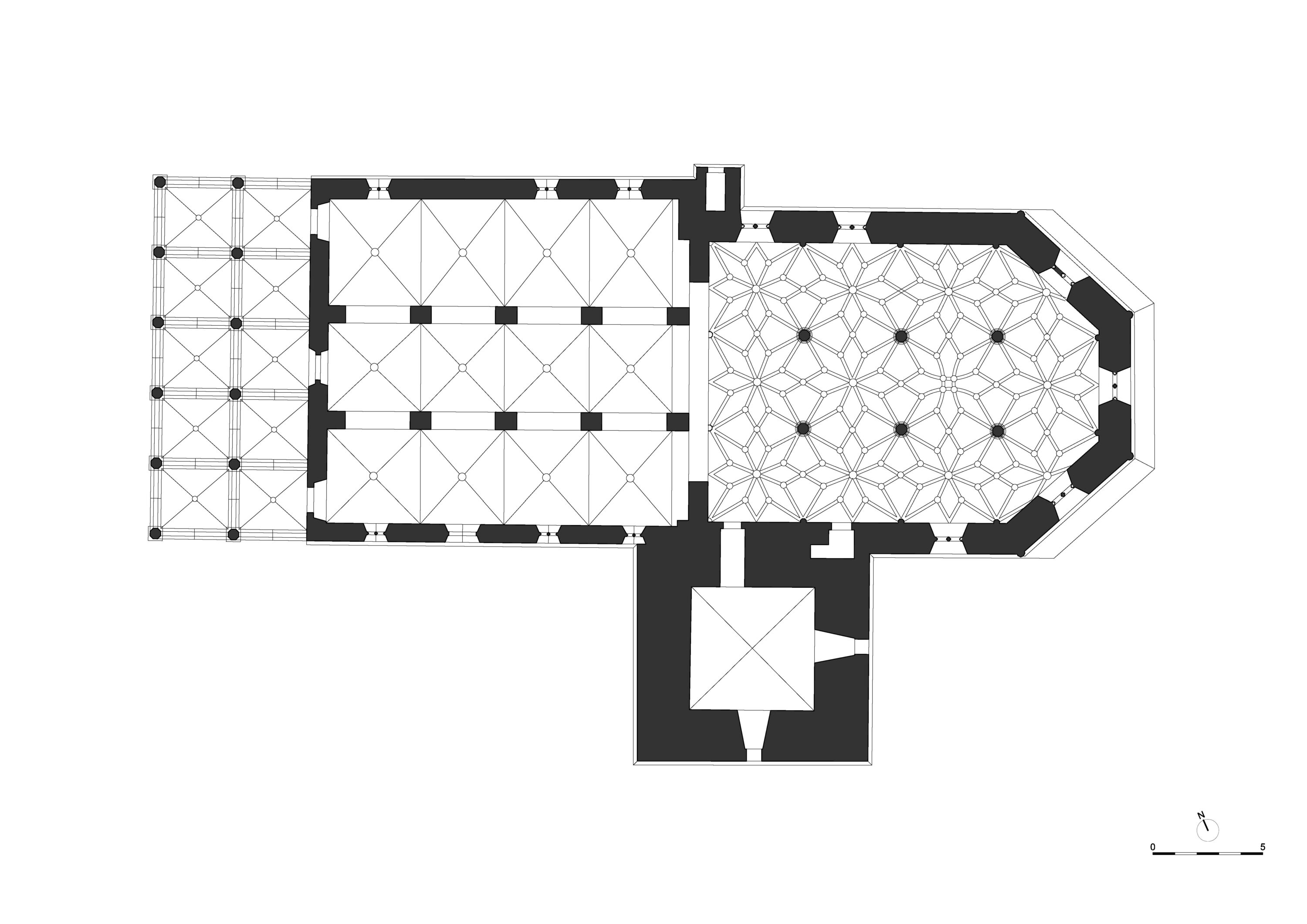

Architecturally, it is a staggered three-nave church (Staffelkirche) with a chancel terminated by three sides of an octagon.[4] The chancel is particularly notable for its size, as it is taller than the central part of the church and almost identical in width and length to the nave part.[5] It features a stellar vault set on six octagonal columns forming the three “naves”.[6] This architectural design is of remarkable significance, as it is the only example of a three-naved hall chancel in Slovenia[7] in the tradition or succession of the Upper Carniolan hall churches characteristic of the second half of the 15th century.[8] A look at the older, central part of the church reveals that it features rib vaulting in the nave and the two aisles.[9] The same type of vaulting is once again found in the church’s neo-Gothic portico.[10] The church’s image is completed by a belfry with a bulbous roof, erected on the southern side of the church at the transition from the nave to the chancel.

The very shape of today’s building reveals that its construction took place over several centuries.[11] It is possible to identify five major construction phases leading to the church’s present architectural image. The Crngrob church was constructed at the end of the 13th century, initially as a single-nave Romanesque church.[12] Its width amounted to half of today’s nave, reaching the middle of it, and it was about three metres high.[13] The still-preserved northern aisle’s northern wall[14] and a part of its eastern wall were also part of the original construction. This building was probably topped by a semi-circular apse.[15] The murals of the Crucifixion on the former eastern wall (now the triumphal arch) and the Cycle of the Virgin Mary in the lower band, which used to extend from the middle of the aisle’s northern wall further on to the eastern wall, were painted at the end of the 13th and the beginning of the 14th centuries.[16] These murals represent the oldest mural layers in the Crngrob church.[17] As the cycle representing the Life of the Virgin starts out in the middle of the wall, researchers initially assumed that the church was originally half as long.[18] However, since archaeological research could not confirm this in 1984, it was assumed that already back then, the church had been as long as its present northern wall.[19] In the 14th century – more precisely, around 1370–1380 – the western façade was painted. Today, it still features a partially preserved Passion Cycle, painted by the provisionally named the Crngrob Façade Master.[20] Only a few decades later, at the beginning of the 15th century, the Passion Cycle, attributed to a Friulian workshop, was also painted above the older Marian cycle on the interior northern wall of the then single-nave church.[21]

During the next construction phase, in the middle of the 14th century, the church was raised by 1.30 metres, while after 1410, it was enlarged to a double-nave church.[22] At that point, the two window openings in the eastern part of the northern wall were also built, while the northern aisle was vaulted before 1453.[23] This year serves as the terminus ante quem for the vault – i.e. the year by which the aisle had been vaulted, as it was painted at that point by Master Bolfgang.[24] His mural covered the eastern, northern, and southern walls of the northern aisle’s eastern bay.[25] The most renowned part of this mural is the preserved half of the Nativity scene, in which Joseph is cooking gruel.[26]

The third and final rebuilding of the nave was carried out between 1460 and 1464.[27] At that point, the church was enlarged into a three-nave church, giving the hall for worshippers the appearance it has today.[28] A new portal was added in the centre of the newly-built western façade, leading into the nave, while the nave and the southern aisle were vaulted somewhat later.[29] The entire alteration was overseen by the builder known as the Master of Mengeš. His stonemason’s mark has been preserved in the centre of the main portal’s lintel.[30] At that time, the nave and the two aisles each featured its own chancel termination, as attested by the contract for the construction of the new chancel and belfry, concluded with Master Jurko from Loka in 1520.[31] The dating of this construction stage is associated with the murals painted in the church at the time.

Around 1460, a depiction of Holy Sunday or Sunday Christ was painted on the southern side of the western façade by Johannes of Ljubljana’s workshop;[32] while in 1464, Master Bolfgang also added the image of St Christopher on the southern façade.[33] During the fourth stage, the present chancel with the stellar vault was added to the church, as evidenced by the abovementioned contract with Master Jurko from 1520.[34] The latter also made the keystones in the chancel, although the finest of them – the one with the image of the Virgin Mary above the high altar – is attributed to Master HR.[35] Master Jurko also erected the belfry, which was raised by two storeys in 1551. In 1661, it was raised even further and covered with a bulbous roof, resulting in its present appearance.[36] Before the completion of the belfry in 1644, the vault of the chancel had been decoratively painted.[37]

The church attained its final architectural appearance in 1858 when the builder Giovanni Battista Molinaro from Loka added a neo-Gothic portico in front of the church’s western wall.[38] Furthermore, during the same century – more precisely, in 1863 – the final mural was added: the painter Janez Gosar’s full-length image of St Christopher on the western wall of the belfry.[39]

________________________________________

[1] ZADNIKAR 1973, pp. 32–33.

[2] KOMELJ 1973, p. 276; ZADNIKAR 1973, p. 33; KOMAN 2004, p. 113.

[3] ZADNIKAR 1973, p. 37. At the beginning of the 20th century, some parts of the mural were still whitewashed. However, already at that time, initiatives to uncover the frescoes were voiced, see Mitteilungen 1908.

[4] ŠTEFANAC 1995, p. 89.

[5] ŠTEFANAC 1995, p. 90.

[6] ŠTEFANAC 1995, p. 90. All columns feature foliated capitals, and a figural band was also added to the eastern pair of the columns above the capitals, see KOMAN 2000, p. 15.

[7] KOMAN 2000, p. 15.

[8] HÖFLER 1996, p. 86.

[9] ZADNIKAR 1973, p. 34.

[10] KOMAN 2000, p. 18.

[11] STELE 1962, p. 6; ZADNIKAR 1973, p. 33.

[12] HÖFLER 1996, p. 86; HÖFLER 2016, p. 378.

[13] HÖFLER 1996, p. 86; KOMAN 2000, p. 10.

[14] HÖFLER 1996, p. 86.

[15] HÖFLER 1996, p. 86; KOMAN 2000, p. 12; see also ZADNIKAR 1973, p. 33. If the northern wall is indeed original throughout its length and the mural only started towards the middle of the wall, we can assume that the church featured a wooden west gallery.

[16] HÖFLER 1996, p. 86.

[17] ZADNIKAR 1973, p. 33.

[18] KOMAN 2000, p. 10.

[19] KOMAN 2000, p. 10.

[20] HÖFLER 1996, p. 86.

[21] HÖFLER 1996, p. 86.

[22] HÖFLER 1996, p. 86; KOMAN 2000, p. 12.

[23] ZADNIKAR 1973, p. 34; KOMAN 2000, p. 12. Although the relevant literature indicates that the church had a belfry in the middle of the 14th century, that was not really the case; see KOMAN 2000, p. 12.

[24] ZADNIKAR 1973, p. 36; HÖFLER 1996, pp. 86, 88; KOMAN 2000, p. 23.

[25] HÖFLER 1996, p. 88.

[26] For information on Master Bolfgang and the 1453 mural, see STELE 1966, pp. 43–44; CEVC 1983, pp. 35–41; HÖFLER 1995a, p. 273; HÖFLER 1999, pp. 343–364; ZADNIKAR 2004, pp. 71–99; CERKOVNIK 2012, pp. 147–157. A copy of this scene is now part of the permanent collection of the National Gallery in Ljubljana.

[27] KOMAN 1998, p. 124; KOMAN 2000, p. 13.

[28] HÖFLER 1996, p. 86; KOMAN 1998, p. 124; KOMAN 2000, p. 13.

[29] KOMAN 1998, p. 124; KOMAN 2000, p. 13. The common characteristic of the piers in the nave is that they are without capitals, while the difference between the piers on the northern side and those on the southern side is in the termination of the bevelled edges. At the same time, the consoles in the southern aisle are designed differently, as well. About this, see KOMAN 1998, p. 125; KOMAN 2000, p. 13.

[30] This Master’s most renowned work is the parish church of St Michael in Mengeš, see KOMAN 1998, p. 125; KOMAN 2000, p. 13.

[31] ZADNIKAR 1959, p. 161; KOMAN 2000, p. 13. The contract with Jurko from Loka was published by LAVRIČ 1986, pp. 135–153.

[32] HÖFLER 1996, p. 86; KOMAN 2000, p. 13. The Crngrob Holy Sunday scene has been the subject of several independent treatments. The most notable contributions on this topic are listed in KOMAN 2004, pp. 128-131; see also STELE 1944, pp. 399–438; CEVC 1958, pp. 144–149; HÖFLER 1995b, pp. 257–258; KOMAN 2022, pp. 33–56; ŠIFRER BULOVEC 2022, pp. 57–80. A copy of this scene is now part of the permanent collection of the National Gallery in Ljubljana.

[33] HÖFLER 1996, p. 86; KOMAN 2000, p. 13.

[34] LAVRIČ 1986, pp. 135–153; KOMAN 2000, p. 14.

[35] ŠTEFANAC 1995, p. 90; KOMAN 2004, p. 125. All the peripheral keystones are carved as rosettes, while the central ones are figural. The four consoles where the vault by the former triumphal arch terminates are also notable; they feature the carvings of two male heads, a female head, and a dog. For a list of the motifs on the keystones and the connection between the consoles and the legend of the Crngrob robbers, see KOMAN 2000, pp. 15–17.

[36] ZADNIKAR 1973, p. 35; KOMAN 2000, p. 18.

[37] KOMAN 2000, pp. 16, 31.

[38] ZADNIKAR 1973, p. 33; KOMAN 2000, p. 18.

[39] ZADNIKAR 1973, p. 33. KOMAN 2000, p. 23.

The oldest Crngrob murals were first examined by France Stele in 1935,[1] who roughly dated all three of the oldest layers – the Crucifixion on the eastern triumphal arch, the cycle representing the Life of the Virgin on the northern wall, and the Passion Cycle scenes on the façade – and identified their stylistic influences.[2] In his discussion of the Last Supper scene, Stele pointed out the obvious influence of Giotto’s mural in the Arena Chapel in Padua and compared the Crucifixion on the triumphal arch wall to the same scene in St Catherine’s Chapel in The Karlstejn Castle in Czechia because of the similar juxtaposition of the figures.[3] He also identified the iconography of almost all scenes: four out of five in the Marian cycle and ten out of the twelve still preserved Passion scenes.[4]

Detailed descriptions of the individual Passion Cycle scenes can be found already a year later in the Crngrob guidebook by the Stara Loka parish priest Janez Veider.[5] He was also the first to mention the possibility that the exceedingly poorly preserved third Marian cycle scene might be a depiction of the Magi.[6] He also identified the remaining two Passion Cycle scenes that France Stele had not identified.[7] Veider’s guidebook was reprinted a little over six decades later as part of the guides around the Loka region. In 1998, a few more recent contributions were added to the original text, exploring both the church and the village of Crngrob.

As the leading researcher of Slovenian medieval mural painting, France Stele continued to write extensively on the Crngrob murals in the following decades. He once again discussed the oldest layers in 1937, in the survey titled Cerkveno slikarstvo med Slovenci (Church Painting Among Slovenians) and in 1938 as part of the report on the uncovering of these murals for the Varstvo spomenikov journal.[8] He also included them in his overviews of medieval painting. In his 1969 monograph, he mentions the Passion Cycle on the façade several times, refers to the Marian cycle as an example of the early Gothic drawing style, and underlines the Byzantine style of depiction in the scene of Mary’s death.[9] The most important feature of the 1972 overview of Gothic mural painting is the schematic outline of the preserved murals with a detailed presentation of the locations of the individual iconographic motifs.[10] Although France Stele focused on the Crngrob murals in his overviews in particular, in 1962, he also devoted an independent treatment in the form of a guide to the monument.[11] According to Dušan Koman, this guide represents one of the most vital scholarly works on the Crngrob church.[12]

Already in 1984, Emilijan Cevc traced the origins of the painter of the Passion scenes on the façade to Bolognese rather than Friulian art circles,[13] which was confirmed by subsequent research.[14] The finding that the artist’s style was shaped under the influence of Bolognese painting was echoed a year later by Janez Höfler, who pointed out the characteristic gesticulation of the figures and the expressiveness of their faces.[15] The Crngrob façade was also included in Robert Peskar’s article on church exterior murals. Peskar underlined that such extensive cycles were painted on church exteriors by Italian or Friulian itinerant painters.[16] Meanwhile, Lev Menaše wrote about the Crngrob Marian cycle in the chapter on the 14th-century Marian cycles and in his discussion of the motif of Mary’s death in his work titled Marija v slovenski umetnosti (Mary in Slovenian Art) in 1994.[17]

In 1995, the Marian cycle scenes and the Passion Cycle on the façade were included in the catalogue Gotika v Sloveniji (Gothic in Slovenia), where Tanja Zimmermann and Adela Železnik wrote about the scenes of the Annunciation, the Nativity, and the Last Supper, as well as about the fragment of Christ’s prayer on the Mount of Olives.[18] Tanja Zimmermann underlined the significance of the Marian cycle and defined it stylistically,[19] while Adela Železnik emphasised the comparison between the Last Supper scene and Bolognese painting, while also focusing on the author of the Passion Cycle, already provisionally named in the catalogue as the Master of the Crngrob Façade.[20] Both authors also wrote short overviews for this catalogue. Tanja Zimmermann discussed the late 13th and early 14th-century painting[21] and pointed out that the Crngrob Marian cycle, together with the oldest murals in the church of St John the Baptist by Lake Bohinj and the church of St Cantianus in Vrzdenec, was the work of the same workshop.[22] Meanwhile, Adela Železnik focused on the 14th and early 15th-century Gorizia workshops and started replacing the term “Friulian travelling workshops” with the collocation “Gorizia workshops”.[23]

Tanja Zimmermann revisited the 13th and 14th-century painting in her doctoral dissertation by including the Crucifixion scene and the Marian cycle from Crngrob.[24] She focused on the stylistic definition of the artist who painted the scenes with the Virgin Mary and on the stylistic comparisons with other works. Thus, she compared some of the figures from the Crngrob Marian cycle with those on the mural paintings in the church of St John the Baptist in Bohinj.[25] She simultaneously associated the style reflected in the scenes from the Life of the Virgin to the painting in the Lake Constance area and the Carinthian region.[26]

In 1996, Janez Höfler included Crngrob in his first overview of medieval frescoes in Slovenia, presenting all the medieval layers of the mural paintings in the Crngrob church.[27] In connection with the Passion Cycle on the façade, he more precisely defined the connection between the Cosmatesque bordure pattern with the examples from Bolognese painting, executed by Vitale da Bologna’s successors.[28] Thus, Janez Höfler no longer states that the Crngrob Façade Master originated from Vitale’s workshop but rather that he came from a workshop headed by one of Vitale’s successors.[29]

In 1998, 2000, and 2015, Dušan Koman also wrote about the Crngrob church murals.[30] He also used the term “Gorizia painters” when discussing the Passion Cycle.[31] Already four years later, in an article on the representation of the Crngrob church in the expert literature, Koman listed all the major works discussing the entirety of the Crngrob mural layers.[32] His article serves as the foundation for any research into this art monument, as the author included the relevant literature for all fields of art – architecture, painting, sculpture, church furnishings, and even musicology – as researchers also had to deal with the painted instruments.

The three oldest mural layers were also discussed in Anabelle Križnar’s review from 2006, where the author explored the technical peculiarities of their execution and devoted separate subchapters to them within the treatment of the Crngrob church mural paintings.[33]

CERKOVNIK 2012

Gašper CERKOVNIK, Freske Mojstra Bolfganga iz leta 1453 v romarski cerkvi v Crngrobu. Okoliščine njihovega odkrivanja leta 1935 in njihova usoda, Acta historiae artis Slovenica, 17/1, 2012, pp. 147–157.

CERKOVNIK 2013

Gašper CERKOVNIK, “Maister Jurko ist schuldig die alltn drey khor abzebrechen”. O starih treh korih romarske cerkve v Crngrobu, Loški razgledi, 60, 2013, pp. 115–126.

CEVC 1958

Emilijan CEVC, Crngrobska pletilja, Loški razgledi, 5, 1958, pp. 144–149.

CEVC 1966

Emilijan CEVC, Slovenska umetnost, Ljubljana 1966.

CEVC 1983

Emilijan CEVC, Ikonografski problem Bolfgangove freske Rojstva v Crngrobu, Loški razgledi, 30, 1983, pp. 35–41.

CEVC 1984

Emilijan CEVC, Nova umetnostnozgodovinska odkritja v Crngrobu, Loški razgledi, 31, 1984, pp. 33–39.

GLAVAN 1998

Andrej GLAVAN, Obnovitvena dela in duhovno dogajanje v Crngrobu, Crngrob in okoliške vasi (ed. Ivanka Porenta Aleš), Škofja Loka 1998 (Vodniki po loškem ozemlju, 7), pp. 193–206.

Historična topografija 2021

Historična topografija Kranjske (do leta 1500), Ljubljana 2021 (Slovenska historična topografija, 1), https://omp.zrc-sazu.si/zalozba/catalog/view/1322/5572/1565.

HÖFLER 1985

Janez HÖFLER, Stensko slikarstvo na slovenskem med Janezom Ljubljanskim in Mojstrom sv. Andreja iz Krašc, Ljubljana 1985.

HÖFLER 1995a

Janez HÖFLER, Kristusovo rojstvo, Gotika v Sloveniji (ed. Janez Höfler), Narodna galerija, Ljubljana 1995, p. 273.

HÖFLER 1995b

Janez HÖFLER, Sveta Nedelja, Gotika v Sloveniji (ed. Janez Höfler), Narodna galerija, Ljubljana 1995, pp. 257–258.

HÖFLER 1996

Janez HÖFLER, Srednjeveške freske v Sloveniji. 1: Gorenjska, Ljubljana 1996.

HÖFLER 1999

Janez HÖFLER, O Mojstru Bolfgangu in nekaterih pogledih na srednjeveško stensko slikarstvo v Sloveniji, Raziskovanje kulturne ustvarjalnosti na Slovenskem. Šumijev zbornik (ed. Jadranka Šumi), Ljubljana 1999 (Razprave Filozofske fakultete), pp. 343–364.

HÖFLER 2016

Janez HÖFLER, O prvih cerkvah in župnijah na Slovenskem. K razvoju cerkvene teritorialne organizacije slovenskih dežel v srednjem veku, Ljubljana 20162, http://www.dlib.si/details/URN:NBN:SI:doc-XT3D6JUK.

HÖFLER 2017

Janez HÖFLER, Gradivo za historično topografijo predjožefinskih župnij na Slovenskem. Kranjska, Ljubljana 2017, http://www.sistory.si/SISTORY:ID:38022.

KOMAN 1998

Dušan KOMAN, Veiderjev Vodič po Crngrobu in današnje stanje spomenikov, Crngrob in okoliške vasi (ed. Ivanka Porenta Aleš), Škofja Loka 1998 (Vodniki po loškem ozemlju, 7), pp. 117–132.

KOMAN 2015

Dušan KOMAN, Cerkev Marijinega oznanjenja v Crngrobu, A glej, na tem polju je obrodil stoteren sad. Zbornik Župnije sv. Jurija Stara Loka (eds. Alojzij Pavel Florjančič, Helena Janežič), Ljubljana 2015, pp. 265–279.

KOMAN 2000

Dušan KOMAN, Crngrob, Ljubljana 2000 (Kulturni in naravni spomeniki Slovenije, 201).

KOMAN 2004

Dušan KOMAN, Crngrobska cerkev v strokovni literaturi, Loški razgledi, 51, 2004, pp. 113–141.

KOMAN 2022

Dušan KOMAN, Ikonografski motiv Svete Nedelje v evropski umetnosti. Okoliščine nastanka, Loški razgledi, 69, 2022, pp. 33–56.

KOMELJ 1973

Ivan KOMELJ, Gotska arhitektura na Slovenskem. Razvoj stavbnih členov in cerkvenega prostora, Ljubljana 1973.

KRIŽNAR 2006

Anabelle KRIŽNAR, Slog in tehnika srednjeveškega stenskega slikarstva na Slovenskem, Ljubljana 2006.

LAVRIČ 1986

Ana LAVRIČ, Pogodba z mojstrom Jurkom iz Loke za zidavo prezbiterija in zvonika v Crngrobu, Razprave/Dissertationes, 15, 1986, pp. 135–153.

MENAŠE 1994

Lev MENAŠE, Marija v slovenski umetnosti, Celje 1994.

Mitteilungen 1908

Mitteilungen der k. k. Zentral-Kommission für Erforschung und Erhaltung der Kunst- und Historischen Denkmale, 7/3, 1908, pp. 208–209, 366–367.

PESKAR 1995

Robert PESKAR, Srednjeveške poslikave cerkvenih zunanjščin v Sloveniji, Gotika v Sloveniji. Nastajanje kulturnega prostora med Alpami, Panonijo in Jadranom (ed. Janez Höfler), Ljubljana 1995, pp. 309–319.

SEDEJ 1985

Ivan SEDEJ, Sto znanih slovenskih umetniških slik, Ljubljana 1985.

STELE 1935

France STELE, Monumenta artis Slovenicae. 1: Srednjeveško stensko slikarstvo, Ljubljana 1935.

STELE 1937

France STELE, Cerkveno slikarstvo med Slovenci, 1, Celje 1937.

STELE 1938

France STELE, Crngrob, Zbornik za umetnostno zgodovino, 15, 1938, pp. 95–96.

STELE 1944

France STELE, Ikonografski kompleks slike “Svete Nedelje” v Crngrobu, Razprave SAZU, 2, 1944, pp. 399–438.

STELE 1962

France STELE, Crngrob, Ljubljana 1962 (Spomeniški vodniki).

STELE 1966

France STELE, Oris zgodovine umetnosti pri Slovencih. Kulturnozgodovinski poskus, Ljubljana 19662.

STELE 1969

France STELE, Slikarstvo v Sloveniji od 12. do 16. stoletja, Ljubljana 1969.

STELE 1972

France STELE, Gotsko stensko slikarstvo, Ljubljana 1972 (Ars Sloveniae).

ŠIFRER BULOVEC 2022

Mojca ŠIFRER BULOVEC, Posvetni prizori na freski Sveta Nedelja v Crngrobu, Loški razgledi, 69, 2022, pp. 57–80.

ŠTEFANAC 1995

Samo ŠTEFANAC, Crngrob, p. c. Marijinega vnebovzetja. Kor, Gotika v Sloveniji (ed. Janez Höfler), Narodna galerija, Ljubljana 1995, pp. 89–91.

VALVASOR 1689

Janez Vajkard VALVASOR, Die Ehre des Hertzogthums Crain, 8, Nürnberg 1689.

VEIDER 1936

Janez VEIDER, Vodič po Crngrobu, Škofja Loka 1936.

ZADNIKAR 1959

Marijan ZADNIKAR, Romanska arhitektura na Slovenskem, Ljubljana 1959.

ZADNIKAR 1973

Marijan ZADNIKAR, Spomeniki cerkvene arhitekture in umetnosti, 1, Celje 1973.

ZADNIKAR 2004

Tomaž ZADNIKAR, Mojster Bolfgang na Gornjem Porenju. Nekateri novi viri za sliko Kristusovega rojstva v Crngrobu, Zbornik za umetnostno zgodovino, n. s. 40, 2004, pp. 71–99.

ZIMMERMANN 1995a

Tanja ZIMMERMANN, Stensko slikarstvo poznega 13. in zgodnjega 14. stoletja, Gotika v Sloveniji (ed. Janez Höfler), Narodna galerija, Ljubljana 1995, pp. 221–223.

ZIMMERMANN 1995b

Tanja ZIMMERMANN, Angel oznanjenja in Kristusovo rojstvo, Gotika v Sloveniji (ed. Janez Höfler), Narodna galerija, Ljubljana 1995, pp. 228–229.

ZIMMERMANN 1996

Tanja ZIMMERMANN, Stensko slikarstvo poznega 13. in 14. stoletja na Slovenskem, Ljubljana 1996 (doctoral dissertation typescript).

ŽELEZNIK 1995a

Adela ŽELEZNIK, Goriške delavnice 14. in zgodnjega 15. stoletja, Gotika v Sloveniji (ed. Janez Höfler), Narodna galerija, Ljubljana 1995, pp. 237–238.

ŽELEZNIK 1995b

Adela ŽELEZNIK, Kristus na Oljski gori in Zadnja večerja, Gotika v Sloveniji (ed. Janez Höfler), Narodna galerija, Ljubljana 1995, pp. 239–240.

________________________________________

[1] STELE 1935, p. 41.

[2] STELE 1935, p. 41.

[3] STELE 1935, p. 41.

[4] STELE 1935, p. 41.

[5] VEIDER 1936.

[6] VEIDER 1936, p. 6.

[7] VEIDER 1936, pp. 10, 12.

[8] STELE 1937, pp. 116, 132, 288; STELE 1938, pp. 95–96.

[9] STELE 1969, pp. 20, 33–34, 68–69, 102, 110, 113, 120, 134, 136, 256, repr. 55.

[10] STELE 1972, pp. 10–11, 27, 35, 52–53, repr. 5, 18.

[11] STELE 1962.

[12] KOMAN 2004, p. 121.

[13] CEVC 1984, p. 36.

[14] HÖFLER 1996, p. 90; KOMAN 1998.

[15] HÖFLER 1985, p. 8. The painting is a late-period (after 1348) Vitalesque example.

[16] PESKAR 1995, p. 311.

[17] MENAŠE 1994, pp. 265–266, 286.

[18] ZIMMERMANN 1995b, pp. 228–229; ŽELEZNIK 1995b, pp. 239–240.

[19] ZIMMERMANN 1995b, pp. 228–229.

[20] ŽELEZNIK 1995b, pp. 239–240.

[21] ZIMMERMANN 1995a, pp. 221–223.

[22] Already in 1966 (CEVC 1966, p. 52), Emilijan Cevc grouped the oldest layers of the murals in Crngrob, Bohinj, and Vrzdenec together due to stylistic reasons. However, at that point, he did not yet explicitly state that they were the work of the same workshop. Meanwhile, in her discussion of the Angel of the Annunciation and the Nativity scene, Tanja Zimmermann (ZIMMERMANN 1995b, p. 229) wrote that the Crngrob mural was stylistically associated with the mural in the succursal church of St Thomas in Sv. Tomaž above Praprotno. A year later, Janez Höfler (HÖFLER 1996, p. 10) attributed the Sv. Tomaž above Praprotno mural to the same workshop that had also painted the murals in Crngrob, Vrzdenec, and Sv. Janez by Lake Bohinj.

[23] ŽELEZNIK 1995a, pp. 237–238.

[24] ZIMMERMANN 1996, pp. 57–61.

[25] ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 59.

[26] ZIMMERMANN 1996, pp. 60–61.

[27] HÖFLER 1996, pp. 86–92.

[28] HÖFLER 1996, p. 90.

[29] HÖFLER 1996, p. 91; KOMAN 1998, p. 129; KOMAN 2000, p. 21.

[30] KOMAN 1998, pp. 128–132; KOMAN 2000, pp. 20–31; KOMAN 2015, pp. 271–274.

[31] KOMAN 2000, p. 22.

[32] For the literature dealing with all layers of the Crngrob frescoes – except the Holy Sunday scene, which is discussed elsewhere in the text – see KOMAN 2004, pp. 126–128.

[33] KRIŽNAR 2006, pp. 137–150.

The oldest layer of murals was uncovered in 1935[1] by France Stele, Matej Sternen,[2] the painting student Franjo Golob,[3] and the Stara Loka parish priest Janez Veider.[4] Further conservation and restoration works took place in 1996 when the murals were cleaned and partially protected.[5]

________________________________________

[1] STELE 1938, pp. 95–96; ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 198.

[2] HÖFLER 1996, p. 86.

[3] STELE 1938, p. 95.

[4] KOMAN 2004, p. 126.

[5] GLAVAN 1998, p. 201.

Legal Terms of Use

© 2026 ZRC SAZU UIFS, Corpus picturarum muralium medii aevi

ZRC SAZU

France Stele Institute of Art History

Novi trg 2

1000 Ljubljana

Spodaj seznam podrobno opisuje piškotke, ki se uporabljajo na našem spletnem mestu.

| Cookie | Type | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| _ga | Non-Necessary | 2 years | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. The cookie is used to calculate visitor, session, camapign data and keep track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookies store information anonymously and assigns a randoly generated number to identify unique visitors. |

| _gat | Non-Necessary | 1 minute | Google uses this cookie to distinguish users. |

| _gid | Non-Necessary | 1 day | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. The cookie is used to store information of how visitors use a website and helps in creating an analytics report of how the wbsite is doing. The data collected including the number visitors, the source where they have come from, and the pages viisted in an anonymous form. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | Necessary | 1 year | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-non-necessary | Necessary | 1 year | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Non Necessary". |

| CookieLawInfoConsent | Necessary | 1 year | The cookie is used to store the summary of the consent given for cookie usage. It does not store any personal data. |

| PHPSESSID | session | Time of session | Cookie stores information about the user's session and allow users to keep their entries during the time of visiting the website. |

| pll_language | Necessary | 1 year | This cookie is used to remember any selection a user has made about language. |

| show_preloader_once | Necessary | Session | With this cookie we remember the user's first visit. |

| viewed_cookie_policy | Necessary | 1 year | The cookie is used to store whether or not you have consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |