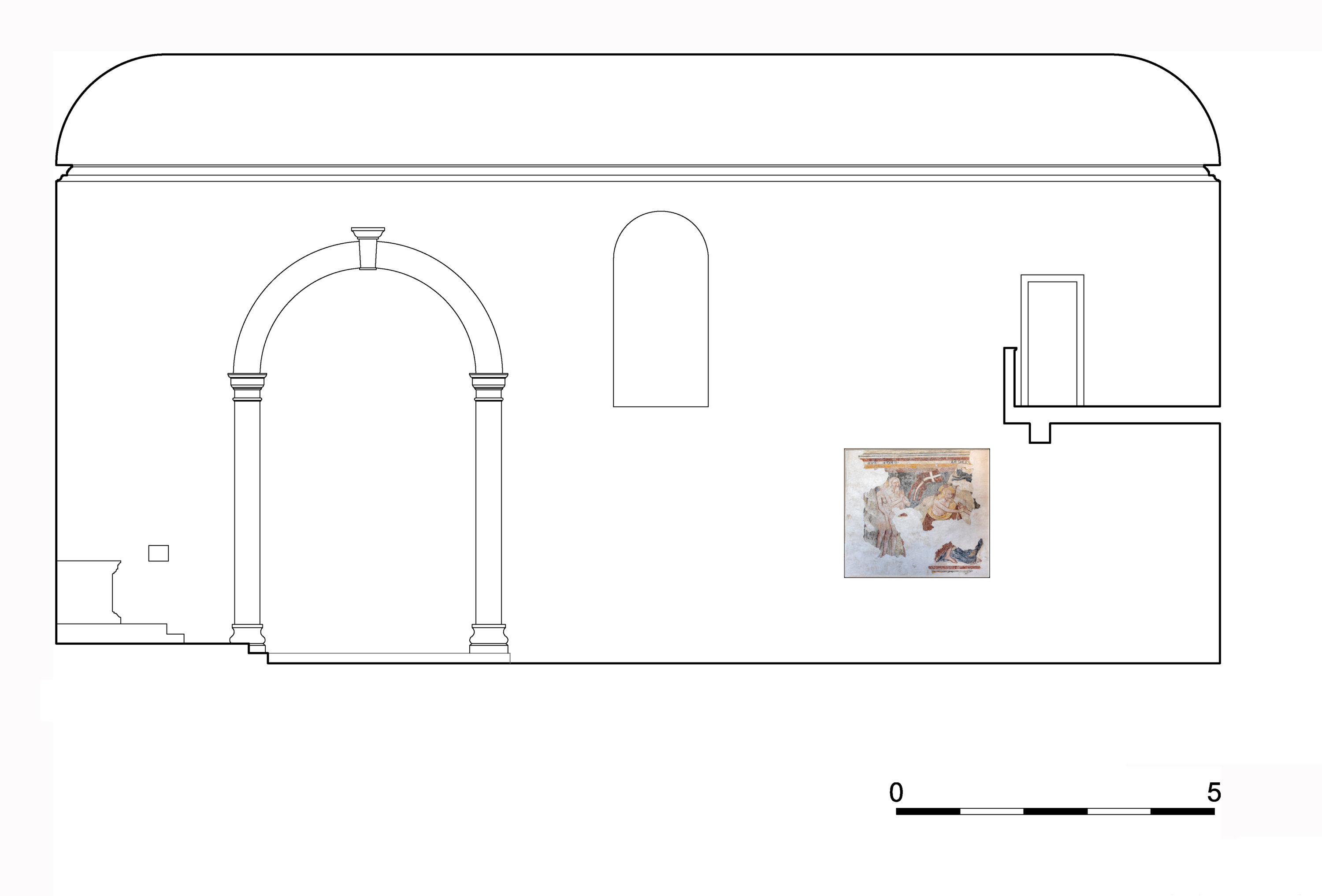

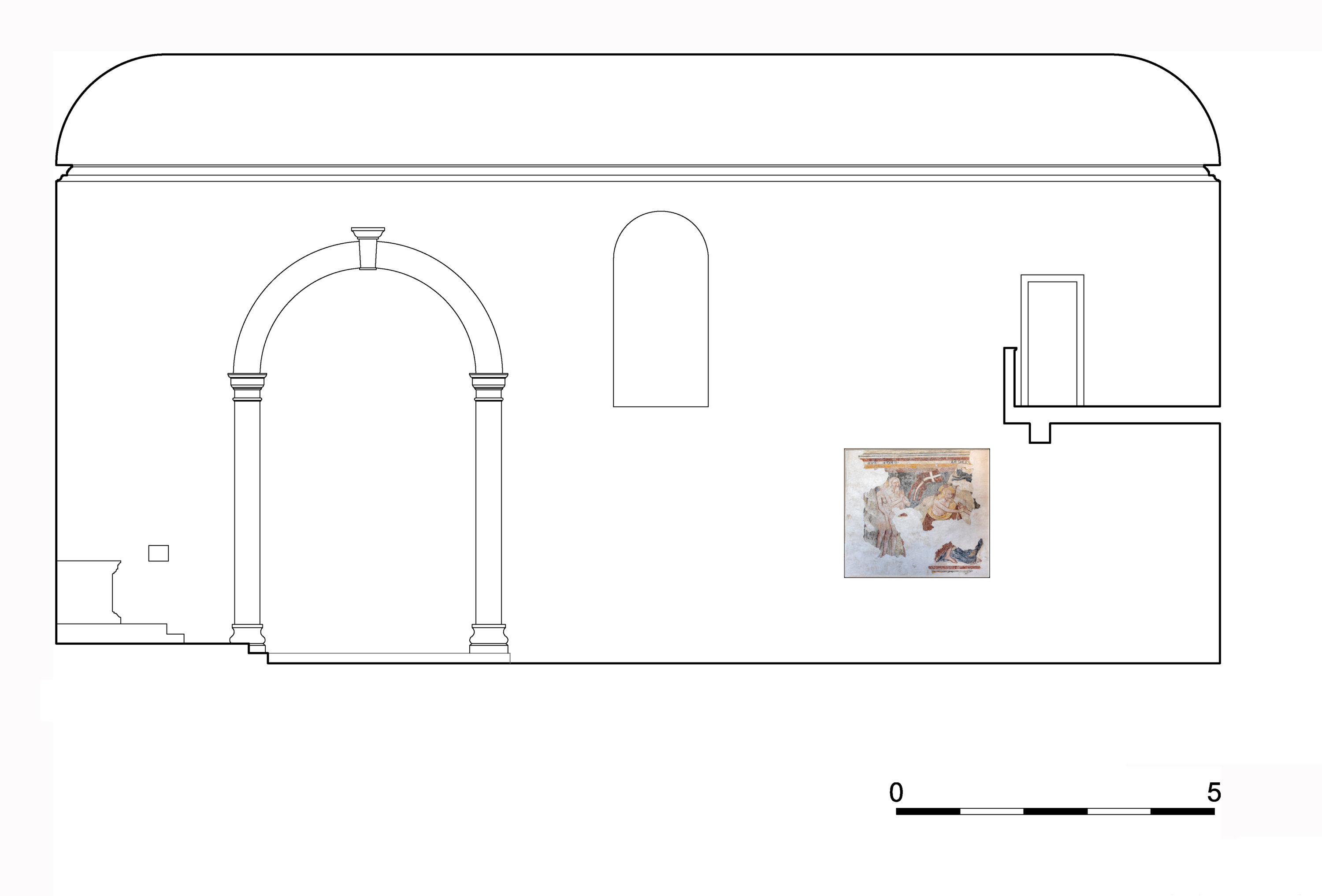

On the southern wall of the nave, just in front of the choir loft, a fragmentary mural depicting Christ in Limbo was discovered in the 1990s.[1] The visible remains suggest that this was not a single scene but most probably a cycle: the painting seems to have been divided into at least two, perhaps even three sections.[2] The uncovered scene is framed by a simple border with stripes painted in red, white, yellow, and red again (only white and red on the lower edge). The white border above the figures bears the names EVA, ADAM and REDE[M]P[T]O[R] in Gothic script. Adam and Eve are standing on the left side of the scene, in front of the hillside, both naked. Adam stands before Eve with his hands clasped in prayer. Christ the Redeemer is depicted on the right side of the scene, wearing a red cloak with yellow edging in the upper part of the garment, which extends over his left shoulder and down to his waist on the other side. In his left hand, he holds a pole with a banner (a white cross on red background), while with his right, he grips the kneeling Satan, of whom only an arm and a leg remain, by the wrist.[3]

________________________________________

[1] QUINZI 1999, p. 9.

[2] Cf. QUINZI 1999, p. 10.

[3] Cf. QUINZI 1999, p. 10.

Good.

The newly discovered fresco was stylistically defined by Alessandro Quinzi in a 1999 contribution,[1] describing the artist as an above-average master who had developed his painting style by studying the work of Vitale da Bologna. The latter worked in the Udine Cathedral between 1348 and 1349 and greatly influenced the painting style in Friuli in the second half of the 14th century.[2] Quinzi found a concrete stylistic comparison to the figure of Christ in the figure of St Jacob from the former Ospedale dei Battuti in Udine, as well as in the figure of St Martin from the Cathedral of Venzone. Serena Skerl Del Conte attributed the latter to “Vitale’s first assistant”, with whom he shares a similar manner of colour nuancing, the almond-shaped and bulging eyes, the indicated eyelids, and the sparse, tufted beard.[3] Based on the stylistic comparisons, Quinzi also placed the Biljana fresco painter in the first generation of masters who had established themselves immediately after Vitale’s departure from Udine.[4]

________________________________________

[1] QUINZI 1999.

[2] For more information about Vitale da Bologna and his activities in Udine between 1348 and 1349, see especially Paolo CASADIO, L’attività udinese di Vitale da Bologna, Artisti in viaggio 1300–1450. Presenze foreste in Friuli Venezia Giulia, Udine 2003, pp. 33–53, and earlier literature.

[3] QUINZI 1999, p. 11. Cf. Serena SKERL DEL CONTE, Nuove proposte per l’attività di Vita le da Bologna e della sua bottega in Friuli, Arte Veneta, 41, 1987, pp. 9-19.

[4] QUINZI 1999, p. 12.

Based on stylistic comparisons, Alessandro Quinzi dated the Biljana fresco to the 1350s. He supported the earlier dating with an iconographically identical but stylistically more recent scene from the Church of St Martin in Terzo d’Aquileia.[1]

________________________________________

[1] Compared to the scene in Terzo d’Aquileia, Quinzi considers the Biljana mural as compositionally more convincing and solemn, see QUINZI 1999, p. 12.

The fresco depicts a scene of Christ in Limbo, and the figures in the fresco can be identified by the names EVA, ADAM and REDE[M]P[T]O[R] written in Gothic script on the white border. Christ is also characterised by a cruciform halo. In his left hand, he holds a pole with a banner (a white cross on red background), while with his right, he grips the kneeling Satan, of whom only an arm and a leg remain, by the wrist.[1] The fresco was probably a part of a larger narrative of human redemption.[2]

________________________________________

[1] For more information about the iconography, see QUINZI 1999, p. 10.

[2] In Quinzi’s opinion, this kind of iconography corresponds well to the information from the visitation record of Bartolomeo de Portia, which mentions the holy sepulchre and the subsequently installed baptismal font, as the link between Christ’s redemptive passion and baptism was already expressed in Paul’s letter to the Romans. For more information about this, see QUINZI 1999, p. 10; cf. Janez HÖFLER, Srednjeveške freske v Sloveniji. Gorenjska, Ljubljana 1996, pp. 89–90. The scene is of apocryphal origin but has been accepted in the Church tradition; cf. Iacopo DA VARAZZE, Legenda aurea, Torino 1995, pp. 302–306.

Pigments: white lime, yellow earth, red earth, organic black (lampblack?)

Analytical techniques: OM, Raman, XRD

The plaster differs from the older murals in the corner of the northern nave wall. It is very hard and compact and has probably also been consolidated during subsequent restoration works. It looks relatively bright, as also confirmed by the cross-sections. The latter indicate that the plaster consists of lime and aggregate; the visible grains are mostly angular, bright, and translucent (fig. 5). Raman spectroscopy only identified the presence of calcite, while the XRD technique confirmed dolomite – that the plaster therefore contains crushed limestone or even marble, which, together with modest quartz content, is bound with a large quantity of lime. The sparse coloured grains in the mix suggest that some ordinary sand was also added. The plaster is of high quality, bright and solid because of the very materials used. As such, it was an excellent support for painting al fresco, typical of the Italian Trecento tradition. It appears that limewash was added to the secondary areas, which can be discerned under UV light (fig. 6). Unfortunately, only fragments of the mural have been preserved. Therefore, no giornate can be distinguished, though they can almost certainly be inferred from the painting style and technique. As limewash had to be used in some places, the giornate were probably applied over larger surfaces. Therefore, the plaster was already drying before the scene could be finished al fresco.

The colours suggest that mainly earth pigments were used, i.e. yellow and red earth (fig. 5), as well as white lime. The background is blue, and yet the cross-sections do not indicate any azurite (perhaps it has fallen off) but instead reveal black colour on a red underpainting (Fig. 7). In this way, the optical effect of blue could be achieved. The black is of organic origin. Compact lumps of pigment – possibly lamp black – are visible (fig. 7). Black was also used to produce purple colour, which was obtained by mixing red earth with a little bit of black pigment (fig. 6). The binding agent was lime from the plaster as well as lime water or lime milk. For the potential parts carried out a secco, an organic binder was also used.

The well-preserved colours indicate that the mural was painted in the fresco buono technique, as is also confirmed by the cross-sections of the samples and the composition of the plaster. The pigments were impregnated with lime water and applied to the still-fresh plaster. The final details were probably finished dry, though it seems that only a small part of the painting was completed al secco, as even the final contour is still very well preserved. Certain secondary parts, such as the floor, for example, were apparently painted on limewash (fig. 7), as the plaster had dried by the time of the painting, indicating the application of larger giornate.

The preparatory steps are very well hidden behind the colour layers and the final contour. Thus, it is not entirely clear whether Christ’s halo and head were in fact incised with a thin line, as it appears in some places. If any incisions were actually used, they are definitely extremely thin and shallow. We can also not confirm whether the horizontal bordures were also incised as some parts of the upper bordure suggest or whether only a straight red line was used, made with a ruler or perhaps an impression of a string. Such an auxiliary line is still clearly visible under Christ’s foot (fig. 8). The painter may have designed the figures with a different colour, but the underdrawing is not clearly visible anywhere. Only above Christ’s left shoulder does a darker (greenish?) line emerge from beneath the light-coloured background: it was probably the original border of his shoulder, which the painter lowered subsequently (fig. 9). Due to the extensive retouching, the initial modelling is difficult to discern. However, the painter mostly based the designs on the local colour tones applied for carnations, draperies, and backgrounds. It is still possible to determine the use of both broad and thin brushes, which allowed the painter to achieve subtle transitions between light and shadow, thus adding volume modelling to the bodies. Only two male faces have been preserved. Both feature characteristic enlongated and narrow Vitalesque eyes, and the upper eyelids are emphasised with a thicker black line above the eye. Christ’s under-eye bags are accentuated as well. The eyebrows are low and almost straight, with a long nose projecting from the inner eyebrow and terminating in a pointed semi-circular nostril. The mouth is long and fleshy. The faces are modelled in pink, with accentuated brownish shading under the eyebrows, along the nose, under the cheekbones, and on the temples. The long-fingered hands, which appear a bit clumsy, are modelled in the same manner as the entire carnation: with various hues of pink, which is darker towards the edges of the fingers and on the upper side of the hands. The fingers and palm conclude in a dark brown contour, which the painter also used to outline the nails. He would often use the final contour to correct the modelling as well, as we can see, for example, on Christ’s foot or on the fingers of the hand which Christ holds in his right (figs. 8–9). The contour surrounds the entire body. All three preserved figures are rather thickset in the tradition of Trecento painting, carried out in beautiful pink hues transitioning towards brown in the darker areas, such as the edges of the bodies. Christ’s cloak is also modelled in the basic local colours – red and yellow – and with darker shades applied with a broad brush. The painter modelled the rocks on a light grey basic colour layer, adding dark grey shading applied with broad vertical strokes.

Biljana, Parish church of St Michael, Stage 2 (Biljana), 2024 (last updated 16. 10. 2024). Corpus picturarum muralium medii aevi, https://corpuspicturarum.zrc-sazu.si/en/poslikava/phasre-2-biljana/ (3. 12. 2025).

Legal Terms of Use

© 2025 ZRC SAZU UIFS, Corpus picturarum muralium medii aevi

ZRC SAZU

France Stele Institute of Art History

Novi trg 2

1000 Ljubljana

Spodaj seznam podrobno opisuje piškotke, ki se uporabljajo na našem spletnem mestu.

| Cookie | Type | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| _ga | Non-Necessary | 2 years | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. The cookie is used to calculate visitor, session, camapign data and keep track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookies store information anonymously and assigns a randoly generated number to identify unique visitors. |

| _gat | Non-Necessary | 1 minute | Google uses this cookie to distinguish users. |

| _gid | Non-Necessary | 1 day | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. The cookie is used to store information of how visitors use a website and helps in creating an analytics report of how the wbsite is doing. The data collected including the number visitors, the source where they have come from, and the pages viisted in an anonymous form. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | Necessary | 1 year | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-non-necessary | Necessary | 1 year | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Non Necessary". |

| CookieLawInfoConsent | Necessary | 1 year | The cookie is used to store the summary of the consent given for cookie usage. It does not store any personal data. |

| PHPSESSID | session | Time of session | Cookie stores information about the user's session and allow users to keep their entries during the time of visiting the website. |

| pll_language | Necessary | 1 year | This cookie is used to remember any selection a user has made about language. |

| show_preloader_once | Necessary | Session | With this cookie we remember the user's first visit. |

| viewed_cookie_policy | Necessary | 1 year | The cookie is used to store whether or not you have consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |