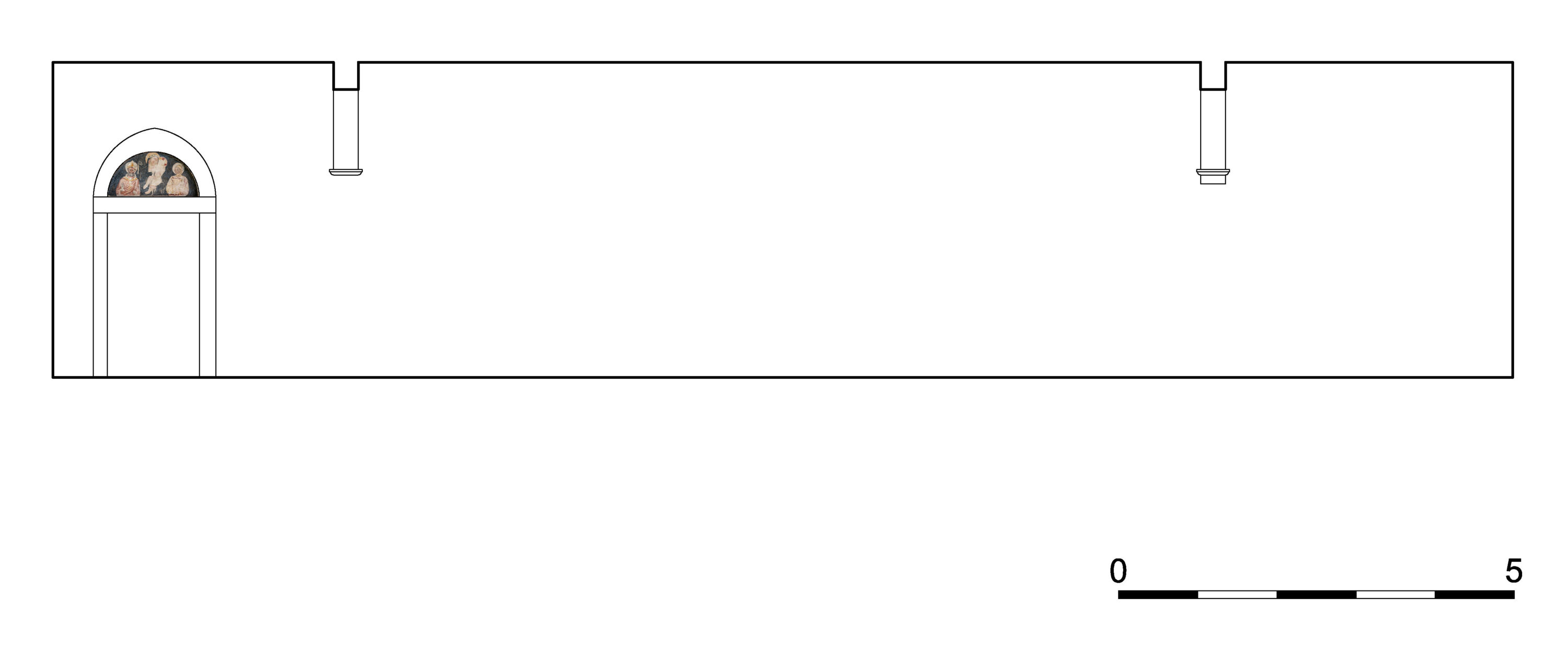

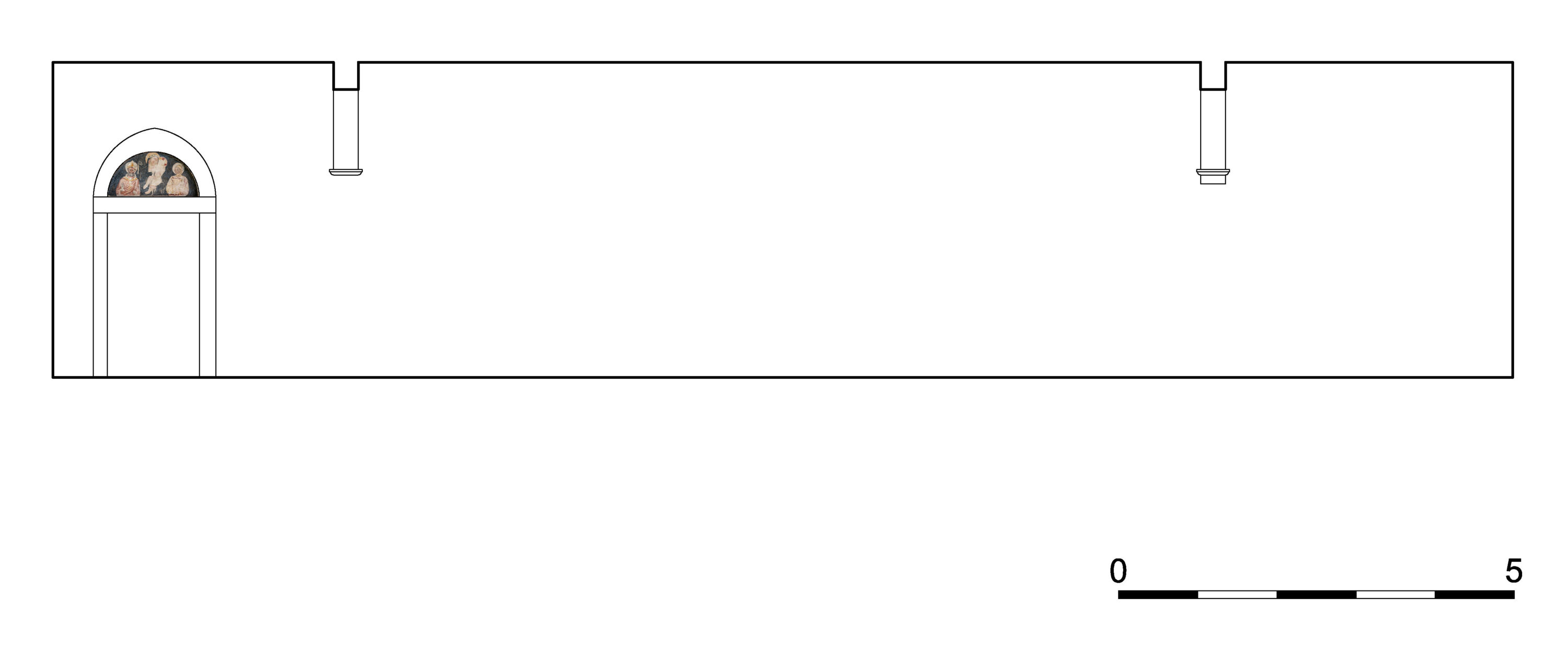

The lunette represents a part of the portal in the cloister that connected the Minorite monastery and the church. Three waist-up figures are depicted on a blue background: Mary with the Child in the centre, a bishop on her left, and most probably a deacon on her right. Mary is wearing a blue cloak, while a broad neckline of a dress of an indeterminable colour (probably yellow) shows from under it. The baby Jesus, cradled in Mary’s arms, sits on her left hand. He hugs her around her neck with his right while his left hand lovingly touches her face. Mary supports his abdomen with her right hand, placed between the baby’s legs. The bishop is wearing white gloves and a red bishop’s vestment with a yellow pallium and a yellow and white mitre, while the deacon is wearing a yellow vestment with red hems and a shoulder-length neckline and a red cape that covers his left shoulder and left arm.

Medium.

Because of the realistic manner in which the Virgin Mary holds the outstretched body of Jesus and the way the saints are depicted, Antonio Alisi considered the fresco to be the work of a vernacular painter. He attributed it to Clerigin, a painter from Koper who often appears in the sources from the middle of the 15th century.[1] Meanwhile, Janez Höfler, who was the last to conduct a more detailed analysis of the fresco, considered it to be of relatively high quality and dated it to the second half of the 14th century.[2] In his stylistic definition, he focused primarily on Mary’s face, which, in his opinion, could not be included in the mainstream of the nearby 14th-century northern Italian painting. In the sharply defined line of the eyes, the long noble nose, and the small mouth highlighted with varnish, he saw certain associations with Rimini and Bologna (Maestro dell’Arengo, Pseudo Jacopino di Francesco, as well as Vitale da Bologna), while he recognised the schematic treatment as distinctly Tuscan or Sienese.[3] Indeed, these types of arrangements were rarer in the nearby northern Italian provinces (Friuli or Veneto) as in Tuscany, but they undoubtedly existed. Already the lunette in the cloister of the Koper Minorite Monastery was repainted in the 15th century with a matching waist-up image of Mary and Child between St Anthony and St Francis.[4] Furthermore, at least one other example of a lunette with a similar waist-up arrangement and the motif of Mary and Child between two saints can be found in Koper – in the lunette of the former chapel on the exterior of Totto Palace. In the province of Veneto, the lunette from the cloister of the San Zeno monastery complex in Verona or the lunette from the northern portal of the Church of San Fermo in Verona can be taken as examples, while in Friuli, it is possible to refer to the lunette from the entrance portal of the church of the Benedictine Abbey of Sesto al Reghena.[5] The still visible stylistic features of Mary’s face and the round face of the deacon with sharp, thinly accentuated lines above the eyes and blushed cheeks indeed suggest – as already pointed out by Jan Höfler – associations with Bologna (Vitale da Bologna, Pseudo Jacopino, Simone dei Crocefissi), while the necklines of Mary and the deacon’s garments suggest that the mural could be dated between the 1340s and the 1380s.

________________________________________

[1] ALISI s. a.

[2] Cf. HÖFLER 1997, p. 99; HÖFLER 2000, pp. 226–227.

[3] Cf. HÖFLER 1997, p. 99; HÖFLER 2000, pp. 226–227.

[4] The fresco was detached at the end of 1939. The works were carried out under the direction of the Trieste Soprintendenza. For photographic materials, see Soprintendenza Archeologia, Belle Arti e Paesaggio del Friuli Venezia Giulia, Ufficio di Belle Arti a Trieste, Archivio fotografico, Capodistria, prov. di Pola, nr. 893, 5728, 5722, 5723.

[5] For Sesto al Reghena, see especially L’Abbazia di Santa Maria di Sesto. L’arte medievale e moderna (edd. Gian Carlo Menis, Enrica Cozzi), Pordenone 2001; Cristina GUARNIERI, Il Maestro del coro Scrovegni e la prima generazione giottesca padovana, Bollettino del Museo Civico di Padova, 100, 2011, pp. 199–224 (with earlier literature). For the Church of San Fermo, see especially I Santi Fermo e Rustico. Un culto e una chiesa in Verona (edd. Paolo Golinelli, Caterina Gemma Brenzoni), Verona 2004. For the murals in the Church of San Zeno in Verona, see Fabio CODEN, Tiziana FRANCO, La basilica di San Zeno, Verona 2019 (with earlier literature).

Between 1340 and 1380.

An Italian fresco painter. The stylistic and iconographic characteristics point mostly to links with Bologna.

Francesco Semi identified the bishop and deacon on Mary’s left and right, respectively, as St Nazarius and St Elijah from Koštabona. Janez Höfler later adopted this opinion as well.[1] The iconographic type of Mary with the Child, where the baby Jesus presses his cheek against Mary’s, hugging her around her neck with one arm, is derived from the Byzantine type of Eleus or Glykophilus.[2] The variations of this iconographic type, which depict a sensual and loving relationship between Mary and Jesus, were quite widespread in 14th-century Italian painting. Many examples of the Eleuse type can be found in Bolognese painting of the second and third quarters of the 14th century (Vitale da Bologna, Pseudo Jacopino, Simone dei Crocefissi). One such instance is Vitale da Bologna’s panel painting Mary with the Child, which is a part of a private collection in Bologna.[3]

________________________________________

[1] SEMI 1975, pp. 396–397; HÖFLER 1997, p. 99; HÖFLER 2000, pp. 226–227. The identification of the saints as St Nazarius and St Elijah is highly probable. However, due to the lack of attributes or inscriptions, it is also possible that they present some other saints.

[2] HÖFLER 2000, p. 226. For more information on the iconographic type of Eleus or Glycophilus, see: Horst HALLENSLEBEN, Das Marienbild der byzantinisch-ostkirchlichen Kunst nach dem Bildstreit, Lexikon der christlichen Ikonographie, 3, Rom-Freiburg-Basel-Wien 1994, coll. 170–172.

[3] The panel painting was once part of the private collection of M. Gold in London (Petts Wood); see Le Madonne di Vitale. Pittura e devozione a Bologna nel Trecento (ed. Massimo Medica), Ferrara 2010, pp. 28–29.

Pigments: presumably white lime, yellow ochre, red earth, organic black, azurite (?)

Analytical techniques: OM

The cross-sections of the acquired samples are not very representative of the plaster. It is nevertheless possible to discern that it contains lime as a binder and an aggregate consisting of translucent, yellowish grains (Fig. 1–2), which are both angular and round and vary significantly in size. The plasters have not been chemically analysed. The mural might have been painted on two layers of plaster: an underlaid rougher arriccio and smoother intonaco on top, as was customary in Italian Trecento painting, and as the restorers established when they removed the scene with Mary and the saints from the wall, where it was painted next to the lunette. The same was determined with regard to the Mary and Jesus scene in the niche of the monastery church chancel.

As chemical analyses have not yet been carried out, we can only make some assumptions regarding the pigments based on the mural’s colours and the granulation of the pigments in the colour layers. The painter certainly used white lime, yellow ochre, red earth, and some organic black. Given that the blue colour is dark, it seems that he did not use azurite but rather a mixture of white and black. This is also confirmed by the sample taken from the blue background (Fig. 3). There is no green colour. The binder is lime from the plaster, while the final details were probably made by adding some organic binder, such as animal glue, casein, or egg yolk.

Given that the colours still adhere well to the base – not only the basic colour layers but also the subsequent colour modelling of the faces and draperies, especially in the case of St Nazarius and on Mary’s face – we could conclude that the mural was mainly painted al fresco. On the other hand, the almost complete loss of the figure of Jesus is surprising, suggesting that it was carried out al secco. The cross-sections reveal that most of the mural was painted on a dry base, as the boundary between the plaster and the colour layer is clearly visible (Fig. 2–3). Some parts were nevertheless applied al fresco, but the plaster seems to have been drying at that point because although the lime has permeated the colour layer, we can already see the formation of a crust, resulting from the carbonation of the plaster (Fig. 1). The predominance of painting on a dry base is surprising, as the mural was painted on two layers of plaster and in the Italian Trecento tradition, where most murals were made al fresco.

It is possible that there is a sinopia under the mural – i.e. a preparatory drawing made on the lower layer of plaster, the arriccio. This can be assumed based on the Italian Trecento style of painting, in which this painting process was common, but, above all, because sinopie were discovered underneath the removed scene with Mary and the saints (which used to be located next to the lunette in question and is now stored at the Restoration Centre of the Institute for the Protection of Cultural Heritage of Slovenia) as well as on the Mary with Jesus scene in the former monastery church. In the case of the mural in the relevant lunette, the sinopia cannot be confirmed with certainty because no parts of the intonaco are missing to reveal the layer of plaster underneath. The lunette mural has been thoroughly retouched, making the evaluation of the painting process rather difficult. The halos were incised in fresh plaster with a double line and decorated with short ray-shaped pouncings around the head. The outlines of the heads were also incised (Fig. 4). Jesus’ halo is clover-shaped, featuring pouncings only on the leaves. The painting does not always precisely follow the incised lines, as can be seen on St Elijah’s head, where the hair depicted on the inside of the face does not exactly adhere to the incised line. The semi-circular top edge of the scene might also have been incised with a thin line. The underdrawing is probably red, but it is impossible to identify it with certainty anywhere, as it is hidden well under the colour layers. For example, a red line can be seen between the carnation and the hair on the upper edge of Mary’s forehead and the lower edge of her right eye, where the pink colour of the carnation extends over the red line (Fig. 4). There are no underpaintings, while the blue background and Mary’s mantle are painted with a mixture of a lot of black and just a little white, applied directly to the plaster (Fig. 3). The scene portrays four figures. There are notable differences in the designs of the male figures, the female figure, and the figure of the child, which was a common manner of depiction in the Middle Ages. The faces of both saints are elongated, featuring prominent cheekbones and long, narrow noses ending in small, beautifully shaped nostrils. While St Nazarius is depicted en face, St Elijah is portrayed in a three-quarter profile, so his inner nostril is almost entirely hidden behind the nasal ridge due to the perspective. The eyes are almond-shaped and end in elongated points towards the temples. A slightly blurred greyish-brown stroke defines the narrow lower and upper eyelids, while the edges of the eyes are accentuated with dark brown contours (a slightly thicker one for the upper eyelid, while we can also see short strokes for the eyelashes on the lower one). The almost straight eyebrows are placed not too high above the eyes. They are only slightly arched, while the area between the eyebrows and the upper eyelids is shaded with a dark ochre colour and, subsequently, also with grey. The mouth is hidden under a moustache, and it is only possible to see the fleshy lower lip, which used to be red, as can still be discerned in the depiction of St Elijah. The male figures’ carnation is darker, based on dark ochre and additionally shaded in ochre and reddish tones. Meanwhile, the deepest shades were painted in brown and grey, which is especially visible under the eyelids, along the nose, and on the lower part of the cheeks near the chin. Finally, the painter applied white highlights to the cheekbones, along the nose, and on the horizontal wrinkles on the forehead, while finishing the work with a red-brown final contour. Mary’s face (and probably also the face of Jesus, which has been destroyed and can no longer be seen) has a rounder, softer shape, while its carnation is lighter and more pink (Fig. 4), as was typical of female and children’s figures over the centuries. The eyes are also almond-shaped; the longer upper eyelid stands out, while the lower eyelid is shorter and semi-circularly accentuated. The upper eyelid is outlined with a thin red line, while the edge of the eyes is accentuated with a dark brown contour. The almost straight, thin eyebrows extend from the nose to the temples. The upper dark contour has fallen off almost entirely, and the bright red line of the initial colour layer is visible underneath. A long, straight nose, which continues from the eyebrows, has been severely damaged, but the same shape as in the case of both saints can still be discerned. The mouth has been almost completely destroyed, but it was probably bright red and fleshy. On the inside of the forehead and eyebrows, along the inside of the nose, and on the cheeks, the painter applied a darker pink, red, and ochre shading to the basic light pink carnation. Thus, the outer side of the forehead and the cheekbones remain bright. He completed the face with a red-brown contour. Identical modelling can be seen on the hands, which appear slightly too small for the body but are elegantly shaped with narrow palms and fingers. The modelling was clearly applied to dry plaster, as the boundary between the plaster and the basic pink colour layer is clear (Fig. 2a). This can be best seen in the relevant cross-section under UV light (Fig. 2b). On top of this basic pink colour layer, it is possible to see white highlights, corresponding to the colour modelling at the point where the sample was taken. St Nazarius wears white gloves, shaded with grey tones and outlined with a black contour. Some parts of the carnation on the figure of Jesus (his feet, the right knee, torso, upper arm, and hands) are still preserved. In those areas, we can also discern light pink basic modelling and shading with darker ochre and pink, while the final contour is reddish-brown. The drapery is modelled with broad strokes of light and shades formed by the folds. As with the carnations, the painter began by applying the chosen basic colour of the garment and then applied the folds using a semi-dry brush in a darker colour, sometimes even in two or three tones (a well-preserved example is the garment of St Nazarius, Fig. 5). He accentuated the tops of the folds with strong white highlights, which have mostly fallen off, though. He always modelled from light to dark, while at the very end, he would apply the white highlights and final dark contours.

Koper, Monastery and Church of St Francis, Stage 2 (Koper, Monastery and Church of St Francis), 2024 (last updated 7. 1. 2025). Corpus picturarum muralium medii aevi, https://corpuspicturarum.zrc-sazu.si/en/poslikava/phase-2-koper/ (27. 8. 2025).

Legal Terms of Use

© 2025 ZRC SAZU UIFS, Corpus picturarum muralium medii aevi

ZRC SAZU

France Stele Institute of Art History

Novi trg 2

1000 Ljubljana

Spodaj seznam podrobno opisuje piškotke, ki se uporabljajo na našem spletnem mestu.

| Cookie | Type | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| _ga | Non-Necessary | 2 years | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. The cookie is used to calculate visitor, session, camapign data and keep track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookies store information anonymously and assigns a randoly generated number to identify unique visitors. |

| _gat | Non-Necessary | 1 minute | Google uses this cookie to distinguish users. |

| _gid | Non-Necessary | 1 day | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. The cookie is used to store information of how visitors use a website and helps in creating an analytics report of how the wbsite is doing. The data collected including the number visitors, the source where they have come from, and the pages viisted in an anonymous form. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | Necessary | 1 year | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-non-necessary | Necessary | 1 year | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Non Necessary". |

| CookieLawInfoConsent | Necessary | 1 year | The cookie is used to store the summary of the consent given for cookie usage. It does not store any personal data. |

| PHPSESSID | session | Time of session | Cookie stores information about the user's session and allow users to keep their entries during the time of visiting the website. |

| pll_language | Necessary | 1 year | This cookie is used to remember any selection a user has made about language. |

| show_preloader_once | Necessary | Session | With this cookie we remember the user's first visit. |

| viewed_cookie_policy | Necessary | 1 year | The cookie is used to store whether or not you have consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |