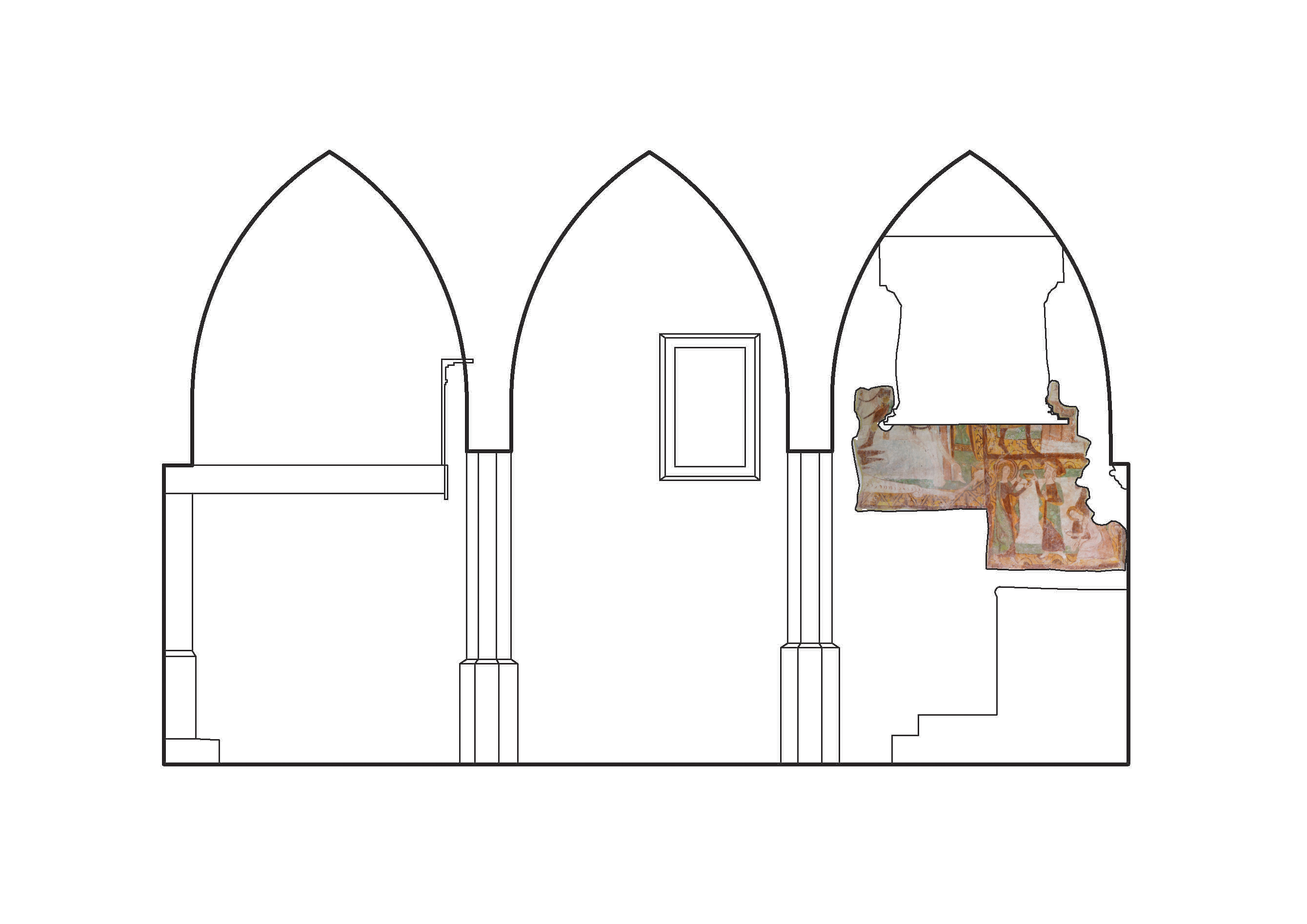

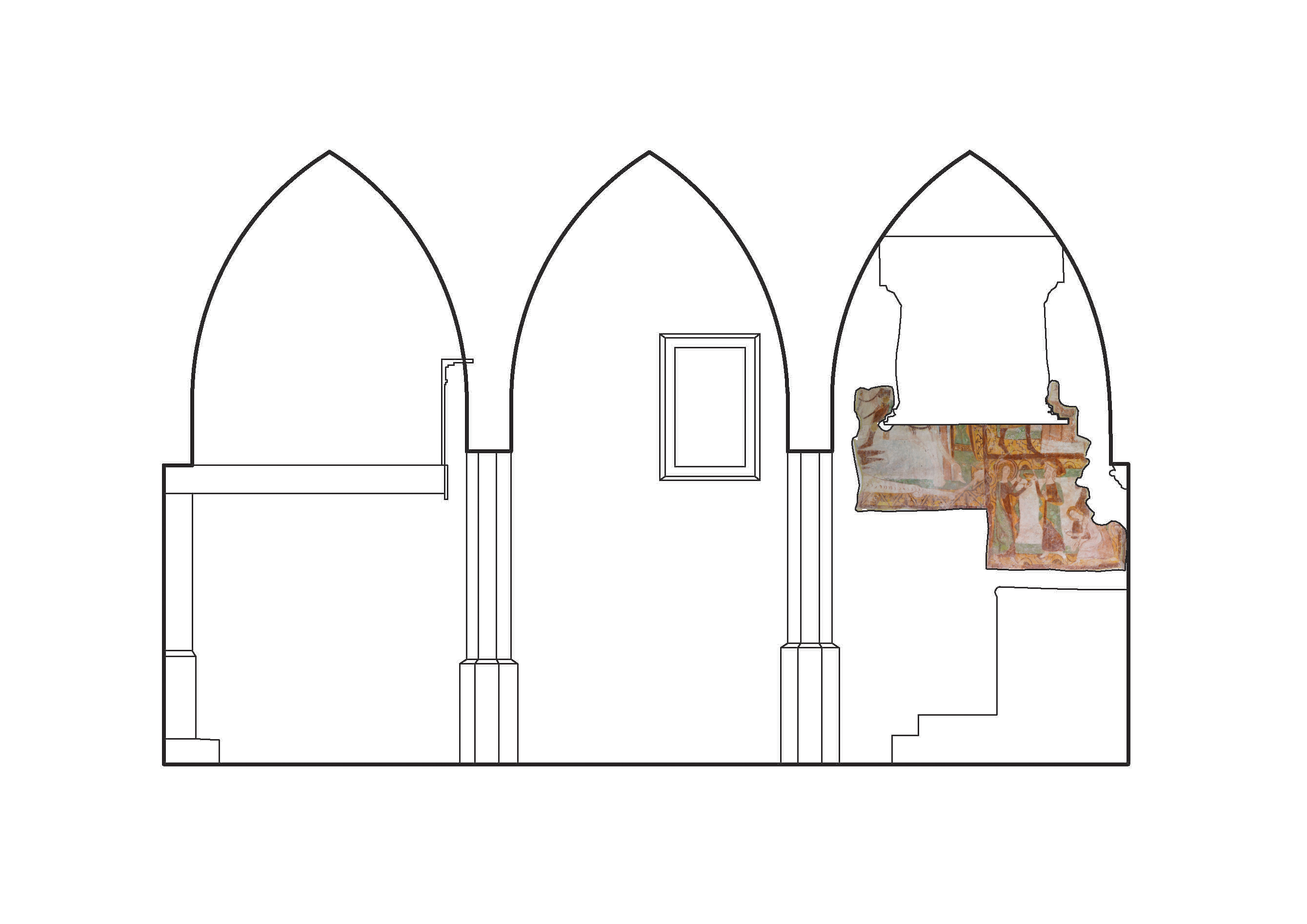

On the northern interior wall of the nave, three scenes belonging to the oldest layer of murals stretch from the triumphal arch towards the west. However, they do not show any tendency to be interrelated in terms of their contents.[1] The following is visible from the viewer’s left towards the right: a part of the scene of St George fighting the dragon; a fragment of an unidentified scene at the top right side; and a fully visible portrayal of St John the Evangelist with a cup of poison in front of the priest Aristodemus in the bottom right.[2] The scenes are therefore not arranged in a horizontal band but rather shifted up and down.[3] They are separated by narrow brown stripes with the addition of a bright tendril[4] and additionally outlined by two thicker bordures.

In 1959, Ivan Komelj was the first to present the iconographic motifs in a conservation report.[5]

While in the literature, the names for the scene with St George only vary in terms of word choice,[6] the fragment above the St John the Evangelist scene is open to various interpretations. In Komelj’s 1959 report, the motif remains unnamed.[7] The same is true of Ksenija Rozman’s 1962 guidebook.[8] In 1965, Ivan Komelj identified the motif on the fragment as one of the scenes of St John the Evangelist before Aristodemus, followed by other interpretations.[9] In 1972, France Stele thus wrote about a fragment of a depiction of St Margaret,[10] and Ksenija Rozman assumed this interpretation in 1984.[11] Meanwhile, Tanja Zimmermann identified the motif fragment as the Arrival of St George to the King and Queen.[12] In Janez Höfler’s medieval fresco overview, the motif is once again unidentified.[13] Regarding the scene with St John the Evangelist, everyone refers to the priest Aristodemus and the act of the saint’s poisoning.[14]

The first scene from the viewer’s left is St George fighting the dragon, of which only the lower part is visible. To the viewer’s right is the frontally depicted princess, her green dress surrounded by a bright decorative band.[15] It is also possible to make out the neck and the hind legs of the white horse ridden by St George,[16] who is facing left with his pointed foot in the stirrup of the saddled horse.[17] It is also possible to identify a part of the bridle, a fragment of the dragon’s wing, and the dragon’s twice-curled tail between the horse’s legs.[18] The still-preserved part of the scene is outlined with a bordure consisting of half-palmettes[19] or palmettes.[20]

The next scene is set at the right edge of the St George scene. It is only fragmentarily preserved, with only its lower edge still visible. The experts disagree about what could have been depicted here. Ksenija Rozman identified a pair of legs stepping from the viewer’s left towards the right side and a part of a yellow woman’s skirt, with what was supposedly the lower part of a pink-coloured tower or building visible behind it on the right.[21] Tanja Zimmermann gives a slightly different description, stating that only a human figure is painted here, apart from a building.[22] On the other hand, Janez Höfler does not mention the building at all but writes that fragments of two people are depicted.[23] Like the first scene, the second one from the viewer’s left is also surrounded by a bordure, though in this case, it features ornamentation consisting of jagged triangles with added semi-circular lines.[24]

The last scene on the northern wall, taken from the legend of St John the Evangelist, was painted to the right of St George and below the unidentified fragment. It contains three figures: the two men on the viewer’s left are turning towards one another, while the figure on the right is bowing at the waist. Although this is not mentioned in the relevant literature, there is another person, possibly a woman wearing a red dress, portrayed behind the figure on the far right, but it is impossible to interpret it clearly because the upper part of the scene has not been preserved. The first figure on the viewer’s left is a young St John the Evangelist with a halo and fair hair of medium length.[25] With his right hand, he is blessing the yellow chalice held in his left.[26] He is wearing a straight tunic and an upper garment wrinkled at the edges.[27] The garment of the figure turning to face St John the Evangelist is painted in the same manner. This is the priest Aristodemus, depicted as a middle-aged bearded man with prominent eyebrows, slightly raised arms, and a distinct headdress.[28] The third figure is a long-haired kneeling person in a white dress, representing, in the words of Tanja Zimmermann, “a victim of poisoning”.[29] Once again, a bordure with a pattern was added, this time consisting of filled half-circles or ellipses, at intervals surrounded by lines,[30] alternating with their longer sides turned towards the bordure’s lower and upper edges. The only bordure common to all three scenes is the green one running along the inner edge of the outer bordure, which is decorated with patterns. Together, these two bordures form the background of the scenes, although the figures are nevertheless depicted in spacelessness.

For several decades after the uncovering of the oldest layer, certain individual details belonging to the depiction of St Christopher were still visible on the southern exterior wall of the nave.[31] According to Ivan Komelj and Ksenija Rozman’s description, the lower hem of the saint’s slightly wider brown garment and the smaller images at his feet, which Ivan Komelj identified as aquatic creatures, were still visible at the time.[32] The depictions included the fish called Faronika, i.e. a crowned female figure with two fish tails; the remains of a horse’s legs, interpreted as the lower part of a centaur; an animal with the body of a mammal and the head of a beaked aquatic creature; a man wearing a pointed cap and holding a hammer in his right hand; and an animal with a dog’s head and horse’s torso.[33] Unfortunately, this mural no longer exists.

________________________________________

[1] HÖFLER 1996, p. 159.

[2] KOMELJ 1959, p. 63; ROZMAN 1962, p. 15; KOMELJ 1965, p. 70; STELE 1972, p. 57; ROZMAN 1984, p. 13; HÖFLER 1996, p. 159; ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 61.

[3] ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 153.

[4] KOMELJ 1959, p. 63; ROZMAN 1962, p. 15.

[5] KOMELJ 1959, p. 63.

[6] KOMELJ 1959, p. 63; ROZMAN 1962, p. 15; KOMELJ 1965, p. 70; STELE 1972, p. 57; ROZMAN 1984, p. 13; HÖFLER 1996, p. 159; ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 61.

[7] KOMELJ 1959, p. 63.

[8] ROZMAN 1962, p. 15.

[9] KOMELJ 1965, p. 70.

[10] STELE 1972, p. 57.

[11] ROZMAN 1984, pp. 13–14.

[12] ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 61.

[13] HÖFLER 1996, p. 159.

[14] There is no single name for this scene in the relevant literature, as the authors merely referred to it descriptively. We can thus find names such as “the Blessing of the poison before the priest Aristodemus” (ROZMAN 1962, p. 15), “Aristodemus attempting to poison John the Evangelist who is blessing the chalice” (ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 61), and “John the Evangelist with the enchanted cup of poison before the priest Aristodemus of Ephesus” (HÖFLER 1996, p. 159).

[15] HÖFLER 1996, p. 159.

[16] ROZMAN 1962, p. 15; ROZMAN 1984, p. 13; HÖFLER 1996, p. 159.

[17] ROZMAN 1962, p. 15; ROZMAN 1984, p. 13.

[18] ROZMAN 1962, p. 15; ROZMAN 1984, p. 13.

[19] ROZMAN 1962, p. 15.

[20] KOMELJ 1959, p. 63.

[21] ROZMAN 1962, p. 15; ROZMAN 1984, p. 13.

[22] ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 61.

[23] HÖFLER 1996, p. 159.

[24] KOMELJ 1959, p. 63; ROZMAN 1962, p. 15.

[25] ROZMAN 1962, p. 15; ROZMAN 1984, p. 15.

[26] ROZMAN 1962, p. 15; ROZMAN 1984, p. 15.

[27] ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 61.

[28] ROZMAN 1962, p. 15.

[29] ROZMAN 1962, p. 15; ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 61.

[30] KOMELJ 1959, p. 63; ROZMAN 1962, p. 15.

[31] ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 61, already states that this mural can no longer be recognised.

[32] KOMELJ 1959, p. 63; ROZMAN 1962, p. 14; ROZMAN 1984, pp. 8–9.

[33] In ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 61, the dog-like creature is omitted.

The murals on the eastern part of the nave’s interior northern wall and the southern exterior were uncovered during the 1957 conservation works, though their existence had been known even earlier.[1]

The murals on the nave’s northern wall have only been fragmentarily preserved.[2] Their sides were destroyed due to the addition of the late Gothic vault, while the upper scenes were ruined in 1563, when the coat of arms of the Bishop of Brixen, Cardinal Cristoforo Madruzzo, was painted on the new plaster.[3] Janez Höfler states that the upper half of the scene with St George is still preserved under the painted coat of arms.[4]

Of the three scenes, the one with St John the Evangelist is in the best condition,[5] while only the lower half of the St George depiction is visible,[6] and only the lower edge of the scene above St John the Evangelist has been preserved.

According to Tanja Zimmerman, the oldest St Christopher layer “can no longer be discerned” as the image has “completely faded”.[7] In this regard, we should take into account that only the lower right edge of the oldest layer with St Christopher was uncovered.[8] Today, this layer is no longer visible, mainly due to its exposure to the elements. In 1962 and 1984, Ksenija Rozman contributed the descriptions of this mural in both guidebooks to the Bohinj church,[9] where she also published photographs showing the individual details of the fragment that is now no longer preserved.[10]

________________________________________

[1] Ksenija Rozman states 1956 as the year of the uncovering (ROZMAN 1962, p. 14; ROZMAN 1984, p. 8). However, as we learn from Ivan Komelj’s report (KOMELJ 1959, p. 62; cf. HÖFLER 1996, p. 158), the oldest mural layers in the Bohinj church were not uncovered until 1957.

[2] KOMELJ 1959, p. 63.

[3] Cf. KOMELJ 1959, p. 63.

[4] HÖFLER 1996, p. 159.

[5] KOMELJ 1959, p. 63.

[6] KOMELJ 1959, p. 63.

[7] ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 61.

[8] HÖFLER 1996, p. 162.

[9] ROZMAN 1962, p. 14; ROZMAN 1984, pp. 8–9.

[10] A photograph of all three layers of the St Christopher murals was published by ROZMAN 1962, fig. 12. The detail of the man with the hammer and the dog-headed animal was published in ROZMAN 1984, p. 9.

The oldest layer of the Bohinj murals belongs to the so-called High Gothic linear style, established at the beginning of the 14th century, which France Stele referred to as the early Gothic drawing style.[1] In Upper Carniola, this style can also be seen, apart from Bohinj, in the succursal church of St Florian in Studenčice, the succursal church of St Clement in Tupaliče, the old parish church of St Oswald in Zgornje Jezersko, the succursal church of St Jacob in Sv. Jakob above Potoče, the succursal church of the Annunciation in Crngrob, and the succursal church of St Thomas in Sv. Tomaž above Praprotno.[2] It is characterised by strong drawing, uniform colour surfaces that are mostly without any shading, and somewhat elongated figures. The mural in Bohinj is a typical example of this style. The figures, faces, and folds of the clothing are drawn with a thicker reddish-brown line. The figures are slightly elongated in height, slim, and painted in three-quarter turns. They have extraordinarily slender arms that appear somewhat glued to the torso, although the protagonists nevertheless gesticulate energetically.[3] The portrayed figures wear long, tightly buttoned garments, falling flatly by their bodies, adorned with ornamental ribbons.[4] In some places, the outer clothing, in particular, is slightly wrinkled, and the folds are shaded, which already shows a tendency towards volume modelling and represents a departure from this planar style.[5] The design of the garments is also more advanced, as they are tight-fitting, while the outer clothing, painted over them, serves as a sort of shell.[6] Tanja Zimmermann refers to such a two-layered manner of designing draperies as “shell-like”, which is a translation of the German term “Körper-Schale-Prinzip”.[7] Precisely because of such “fashion details”,[8] Tanja Zimmermann is one of the few to date the Bohinj mural to as late as the 1420s.[9] The figures also give a floating impression, achieved by painting them standing on the tips of their toes.[10] This further emphasises the effect of spacelessness, which the artist achieved by not including any landscapes or other backgrounds in the scene.[11] This is still a remnant of the Romanesque manner of depicting space by indicating it only with bands that can be monochrome or ornamented.[12] In the mural under consideration, the bordure of the scene with St George includes a palmette motif, which is otherwise typical of Romanesque painting but can still be found in medieval painting in the territory of today’s Slovenia until the first decades of the 14th century.[13]

For the abovementioned scenes, the artist used red-brown, green, and yellow colours. Ivan Komelj stated that the scenes also included pink and sky blue colours, having identified the latter in the spacelessness of the scenes.[14] Ksenija Rozman also wrote about a greyish-blue tone, but only in connection with the background of the St George scene.[15] The palette consisting of green, ochre, and brown-red colours and the conservative stylistic features of the early 14th century connect the Bohinj mural with the paintings on the triumphal arch wall of the succursal church of St Thomas in Sv. Tomaž above Praprotno and in the nave of the succursal church of St Cantianus in Vrzdenec near Horjul, as well as with the Marian cycle depicted on the interior wall of the northern aisle in the succursal church of the Annunciation in Crngrob.[16] In terms of style, the Bohinj mural is most closely related precisely to the Crngrob painting, as the artist who painted the scenes on the oldest layers in Bohinj came from the workshop of another master, which painted the Marian cycle in Crngrob.[17] According to Tanja Zimmermann and Janez Höfler, the latter master headed the local workshop active roughly between the years 1300 and 1320, which also painted the churches in Sv. Tomaž nad Praprotnim and Vrzdenec.[18] If we return to the comparison between the Bohinj and the Crngrob murals, we should also underline the apparent similarity between the facial types and painted clothing, which Tanja Zimmermann demonstrated by meticulously comparing the individual figures.[19] Thus, she associated the design of St John the Evangelist’s face with the depictions of the angels in Crngrob, specifically with the angel in the Annunciation scene and those painted in the Nativity scene.[20] This scene also features the figure of Joseph, for which Zimmermann found stylistic parallels in the facial type of Aristodemus in Bohinj.[21] Both figures are distinguished by their notably broken eyebrows, slanting eyes, and large, straight noses.[22] Meanwhile, Tanja Zimmermann deemed the gesticulation of the Bohinj figures as extremely similar to that of the figures painted in the popular narrative style of Carinthian painting of the second quarter of the 14th century.[23]

Anabelle Križnar determined that the scenes with St George and St John the Evangelist were painted on two layers of plaster. Additionally, based on the analysis of these plasters, Križnar concluded that St George’s fight against the dragon had most likely been painted only after the completion of the two scenes on the right.[24] As the colour layers still adhere very well to the substrate, she established that the mural had been painted on fresh rather than dry plaster, as stated in the older literature.[25]

This leaves the fragment of the oldest layer with St Christopher. Ksenija Rozman identified it as stylistically exceedingly similar to the mural on the northern interior wall. Therefore, she attributed both works to the same artist[26] and labelled them as examples of early Gothic painting.[27] Similarly, France Stele also stylistically defined the oldest of the three layers of the depictions of St Christopher as the Early Gothic drawing style (according to the more recent classification referred to as the High Gothic linear style).[28] Descriptions of the fragment, which is no longer preserved, are scarce. It is only known that both the robe of St Christopher and the bordure of the other figures were painted using a red-brown colour,[29] which, however, is not enough to make a stylistic comparison with the mural on the nave’s northern interior wall.

________________________________________

[1] STELE 1969, p. 134; HÖFLER 1996, p. 159; KRIŽNAR 2006, p. 62. In the older literature, this style may also be referred to as the “plastic drawing style” (KOMELJ 1965, p. 70), “early Gothic style” (ROZMAN 1962, p. 16), and “Early Gothic linear-planar style” (STELE 1972, pp. 9–10).

[2] HÖFLER 1996, p. 10.

[3] ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 61.

[4] HÖFLER 1996, p. 159.

[5] KOMELJ 1959, p. 63; HÖFLER 1996, p. 159.

[6] ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 61.

[7] ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 61.

[8] ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 57.

[9] ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 61.

[10] ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 61.

[11] KOMELJ 1959, p. 63; ROZMAN 1962, p. 16.

[12] HÖFLER 1996, p. 159.

[13] ROZMAN 1962, p. 16.

[14] KOMELJ 1959, p. 63.

[15] ROZMAN 1962, p. 16.

[16] HÖFLER 1996, p. 10; ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 57. Apart from the oldest mural layer in the Bohinj church, CEVC 1966, p. 52, also listed the following murals as examples of the planar style with similar colours and sharp outlines of figures from around 1300 and the beginning of the 14th century: in the succursal church of St Cantianus in Vrzdenec near Horjul; on the northern wall of the northern aisle in the succursal church of the Annunciation in Crngrob; and in the chancel of the succursal church of St John the Baptist in Spodnja Muta.

[17] HÖFLER 1996, p. 159; ZIMMERMANN 1996, pp. 59, 66.

[18] HÖFLER 1996, p. 10; ZIMMERMANN 1995a, p. 222.

[19] ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 62.

[20] ZIMMERMANN 1996, pp. 58–59, 62.

[21] ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 59.

[22] ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 59.

[23] ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 62.

[24] KRIŽNAR 2006, p. 241.

[25] KRIŽNAR 2006, p. 242. The assumption that the mural was painted on dry plaster can be found in KOMELJ 1959, p. 63: “The mural was painted on thin plaster, directly applied to the wall, with limewash applied over the plaster. The basic darker contours were outlined on the limewash, though otherwise, the painting was made using the al secco technique.”

[26] ROZMAN 1984, p. 13.

[27] ROZMAN 1962, p. 16.

[28] STELE 1969, p. 134; KRIŽNAR 2006, p. 62.

[29] ROZMAN 1984, pp. 8–9; HÖFLER 1996, p. 162.

The murals on the northern interior wall of the nave were dated to the first half of the 14th century. The two most widely accepted assessments place their creation to the beginning of the century (to around 1300) and between 1320 and 1330, respectively.[1] Ivan Komelj was the first to date them to the beginning of the century,[2] and his opinion was adopted by Ksenija Rozman, Marijan Zadnikar, and Janez Höfler.[3] At first, Tanja Zimmermann placed their origin to between 1310 and 1320[4] but then changed the dating to the 1420s – i.e. between 1320 and 1330 – based on the so-called two-layered or shell-like manner of designing the painted figures’ clothing.[5] In 1969, France Stele still dated them to the second quarter of that century as well,[6] while in 1972, he placed them to as early as the beginning of the 14th century.[7]

In his 1959 report, Ivan Komelj did not yet date the oldest of the three layers with St Christopher,[8] while in 1962, Ksenija Rozman placed its origin to around 1300.[9] Assuming that the oldest St Christopher layer and the oldest layer of murals on the interior northern wall of the nave were painted by the same master, she dated both of them to the same period.[10] However, if the oldest St Christopher layer is the work of a different painter than the one who painted the interior northern wall of the nave, then Janez Höfler does not rule out the possibility that St Christopher might have been painted already in the late 13th century.[11]

________________________________________

[1] The relevant literature dates the murals to around 1300 (ROZMAN 1984, p. 13; HÖFLER 1996, p. 159; KRIŽNAR 2006, p. 241); shortly after 1300 (ZADNIKAR 1973, p. 64); the beginning of the 14th century (KOMELJ 1959, p. 63; ROZMAN 1962, p. 16; KOMELJ 1965, p. 70; STELE 1972, p. 54; HÖFLER 1996, p. 197); and the period between 1320 and 1330 (ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 194; KRIŽNAR 2006, p. 241).

[2] KOMELJ 1959, p. 63; KOMELJ 1965, p. 70.

[3] ROZMAN 1962, p. 45; ZADNIKAR 1973, p. 64; HÖFLER 1996, p. 197.

[4] ZIMMERMANN 1995b, p. 229. VIGNJEVIĆ 1995, p. 298, also states that the mural was painted around 1320.

[5] ZIMMERMANN 1996, pp. 57, 61.

[6] STELE 1969, p. 39.

[7] STELE 1972, p. 54.

[8] KOMELJ 1959, p. 63.

[9] ROZMAN 1962, p. 45; ZADNIKAR 1973, p. 62; MAČEK KRANJC 1995, p. 266.

[10] ROZMAN 1984, p. 13.

[11] HÖFLER 1996, p. 162.

The scenes on the northern wall of the nave, painted in the 14th century, are attributed to a painter who came from the workshop of the master of the Marian cycle painted on the interior wall of the northern aisle in the succursal church of the Annunciation in Crngrob.[1]

________________________________________

[1] HÖFLER 1996, p. 159; KRIŽNAR 2008, p. 241.

According to France Stele’s findings, the depiction of St George on the northern wall of the nave in the succursal church of St John the Baptist by Lake Bohinj is the oldest depiction of this saint in the territory of today’s Slovenia alongside the St George scenes in the succursal church of St George in Trnovec near Sevnica and in the succursal church of St Cantianus in Vrzdenec near Horjul.[1] It was only towards the end of the century that this motif became somewhat more popular.[2] It was included in sacral spaces mainly because St George was understood as the Christian warrior who conquered evil in the form of a dragon.[3]

The depiction of St Christopher also included various mythological creatures that can also be found in late Romanesque and early Gothic South Tyrolean painting.[4] Because of the depicted mythical creatures and grimacing facial expressions, Janez Höfler points out that the Bohinj murals are related to those in the Sanctuary of San Romedio near Sanzeno and in St James’s Church on the Kastelaz hill in Tramin, both dating from the first half of the 13th century, as well as to the cycle of apostolic martyrdoms in the cloister of Neustift Abbey near Brixen from the early 14th century.[5] The depictions of such creatures originate mainly from medieval mysticism and, in this context, represent the darker sides of life.[6] All the creatures painted on the exterior of the Bohinj church are quite commonplace in the context of the portrayals of St Christopher.[7] The only being that stands out slightly is the male figure with a pointed cap, holding a carpenter’s hammer with a forked claw.[8] Ksenija Rozman ruled out the possibility of a reference to the story of the so-called Bergmandelc, the mountain gnome that startled miners in the tunnels, or that a miner could have been depicted.[9] Thus, she characterised this figure as exceptional.[10]

________________________________________

[1] STELE 1969, p. 90.

[2] Cf. STELE 1969, pp. 89–90.

[3] STELE 1969, p. 89. As an iconographic comparison for the Bohinj mural, ROZMAN 1962, p. 16, already pointed out the mural in the succursal church of St Cantianus in Vrzdenec, namely the scenes of the Arrival of St George to the King and Queen and St George Fighting the Dragon, of which the former was definitely depicted in Bohinj as well. About the Vrzdenec mural, see ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 231.

[4] HÖFLER 1996, p. 162.

[5] HÖFLER 1996, p. 162.

[6] GOLOB 1982, pp. 21–24.

[7] ROZMAN 1962, p. 14.

[8] ROZMAN 1962, p. 14.

[9] ROZMAN 1962, p. 14.

[10] ROZMAN 1962, p. 14.

Pigments: white lime, red earth, mixed blue, malachite, carbon black

Analytical techniques: OM, SEM-EDX, XRD, FTIR

In several places, it appears that the mural is painted on two layers of plaster, with the top layer being very smooth and thin, measuring around 2 mm (fig. 1). The lower layer contains slightly larger sand grains, and it is also coarser to the touch than the upper layer. According to the layout of the plasters, the motif of St George fighting the dragon was created later than the two right-hand scenes, as the plaster layer extends over both edges of the bordure. The cross-sections of the samples taken indicate that the plaster is rich in lime, and the grains of sand are relatively small. Apparently, crushed sand was used, as its grains are of various angular shapes. The fact that the plaster contains a considerable amount of lime and a very low quartz ratio is also confirmed by the results of the X-ray diffraction analyses. The analysis of each of the two visible layers of plaster reveals that the lower layer contains more magnesium but that they are otherwise identical in composition.

The red, green, and blue pigments have been analysed. In the first case, the analyses showed that it is an iron oxide red earth with a strong predominance of iron (Fe) and fewer alumosilicates (Si, Al, Mg, K). It was obviously applied on fresh plaster, as the transition of lime among the pigment grains is clearly noticeable (fig. 2). Nevertheless, it is not very durable, and an organic binder may even have been added to it as well, as in the cross-section, the paint layer appears quite thick. The FTIR measurement technology definitely did not detect the presence of any organic matter, which, however, may be due to the low content in the sample. Despite the soft blue hue in the background of the St John the Evangelist scene, the blue colour does not contain azurite. The analyses only indicated the presence of calcium carbonate and sulphates, so it is probably a mixture of white lime pigment with an undeterminable pigment. The green colour on the bordure is malachite, as the pigment contains a high amount of copper. The binder is mainly lime. The SEM-EDX analysis also showed the presence of barium sulphate, which is occasionally used in restoration and may therefore be the result of former restoration interventions. The surface of the murals has probably also been subject to sulphatisation.

At least the basic colour surfaces, which have survived to the present day, were painted on fresh plaster. This is indicated by the excellent durability of the colour layers, which mainly still firmly adhere to the painting base. They were obviously applied directly on the plaster, as the cross-sections also show. Using two layers of plaster, which allowed for a longer painting time, is also indicative of the al fresco method. The modelling has not been preserved, while the pigments are mostly of earth origin.

No sinopias, incisions, or pouncings can be detected. The underdrawing cannot be discerned anywhere, either, though we can assume that the painter must have used it. Perhaps the contours around the colour surfaces were in fact an underdrawing, which the painter only strengthened when he was completing the works. It is noticeable in several places that he made the brown contours last, as they are peeling off, and we can see other layers of colour underneath. In the background, underneath the blue, there is a light grey or almost white underpainting. All the larger colour surfaces are applied directly on the plaster and can be considered mainly as local tones. The yellow and green colour layers adhere best to the base, so they were probably applied first.

There is virtually no modelling – the painter mainly filled the area between the contours. If we compare the work with the murals in Crngrob and Vrzdenec, we can conclude that the master nevertheless additionally modelled the colours of the basic surfaces subsequently, but that the modelling has not been preserved on this location. The strokes are rough, and the colour was applied with a broad brush in an up-down or left-right direction simply to cover the surfaces. Only two faces have been preserved, revealing the painter’s precise hand in the lines for the eyes, nose, mouth, chin and hair: he knew how to draw fine lines, even though the modelling itself is very simple. The eyebrows are long and slightly semicircular, while the large eyes have a more rounded upper line and a straighter lower line. The painter also used a thin line to highlight the eyelids and the under-eye bags. The nose is long and straight, and the mouth is only indicated with a line.

The hands are narrow and feature long, clumsy fingers. The basic colour surface is pink, the same as the carnation of the face, while the hands and fingers are outlined with a broad chocolate-brown contour. The outer edge of the ring finger and thumb are highlighted with a single long, bright stroke. The hair and the beards are shaped with strong, sinuous lines, made with a broad brush on the base colour surface (brown, light grey), winding from the top of the head towards the shoulders. No additional light modelling is visible. The modelling of the drapery is also simple. Outlined folds are visible on the basic colour surfaces, and in some places, the lines are concluded with a contour about 5 mm thick, outlining the coats. No elements call for the use of stencils.

Ribčev Laz, Succursal church of St John the Baptist, Stage 1 (Ribčev Laz), 2024 (last updated 24. 10. 2024). Corpus picturarum muralium medii aevi, https://corpuspicturarum.zrc-sazu.si/en/poslikava/phase-2-church-of-st-john-the-baptist-ribcev-laz/ (3. 12. 2025).

Legal Terms of Use

© 2025 ZRC SAZU UIFS, Corpus picturarum muralium medii aevi

ZRC SAZU

France Stele Institute of Art History

Novi trg 2

1000 Ljubljana

Spodaj seznam podrobno opisuje piškotke, ki se uporabljajo na našem spletnem mestu.

| Cookie | Type | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| _ga | Non-Necessary | 2 years | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. The cookie is used to calculate visitor, session, camapign data and keep track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookies store information anonymously and assigns a randoly generated number to identify unique visitors. |

| _gat | Non-Necessary | 1 minute | Google uses this cookie to distinguish users. |

| _gid | Non-Necessary | 1 day | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. The cookie is used to store information of how visitors use a website and helps in creating an analytics report of how the wbsite is doing. The data collected including the number visitors, the source where they have come from, and the pages viisted in an anonymous form. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | Necessary | 1 year | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-non-necessary | Necessary | 1 year | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Non Necessary". |

| CookieLawInfoConsent | Necessary | 1 year | The cookie is used to store the summary of the consent given for cookie usage. It does not store any personal data. |

| PHPSESSID | session | Time of session | Cookie stores information about the user's session and allow users to keep their entries during the time of visiting the website. |

| pll_language | Necessary | 1 year | This cookie is used to remember any selection a user has made about language. |

| show_preloader_once | Necessary | Session | With this cookie we remember the user's first visit. |

| viewed_cookie_policy | Necessary | 1 year | The cookie is used to store whether or not you have consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |