Pigments: white lime, yellow earth (goethite), red earth (haematite), azurite, lead white or red (degraded to platernite), organic black

Analytical techniques: OM, Raman, XRD

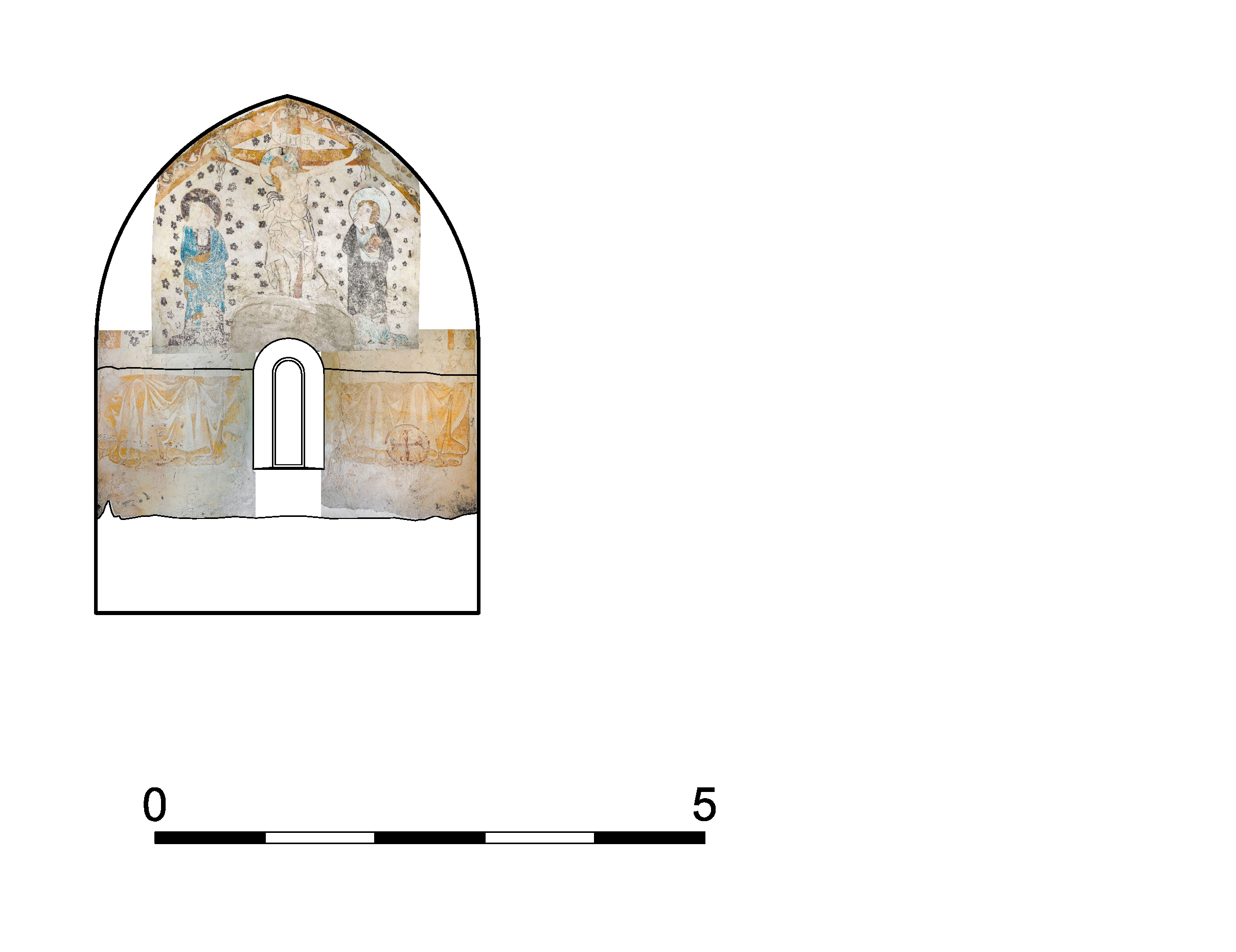

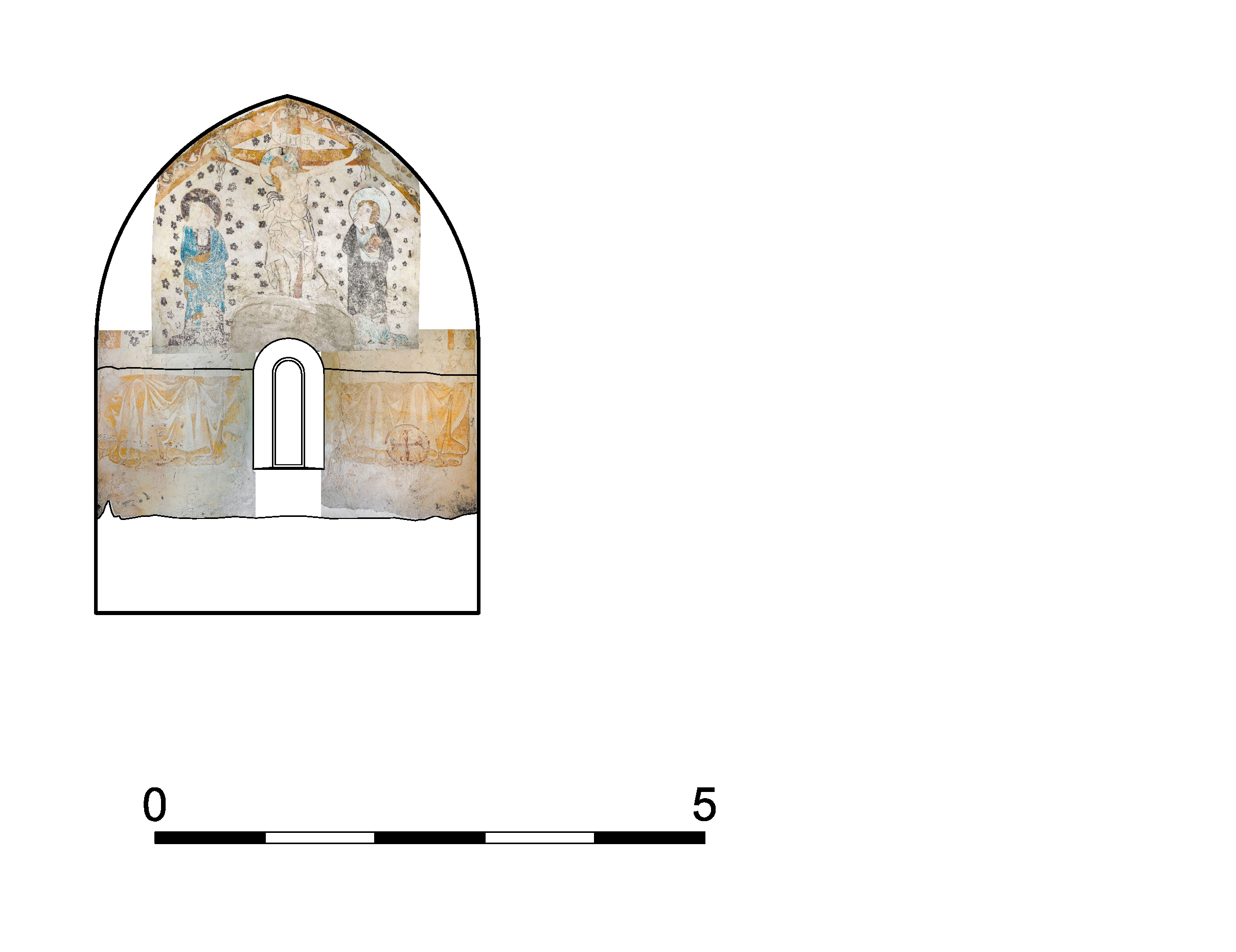

The plaster is very hard, probably due to consolidation. The cross-sections reveal a white base without any aggregate, possibly limewash (Figs 1–2). Raman spectroscopy identified only the presence of calcite, while X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis confirmed a high content of calcite and quartz, being the amount of dolomite and feldspars low. It is a high-quality, hard plaster, bright in appearance due to the predominance of calcite and dolomite (probably as a binder as well as aggregate), as can be seen in the cross-sections. A few giornate can be distinguished, especially on the lower edge of the mural below the figures, but it appears that the upper border was also painted on a new amount of plaster.

Due to the high position of the painting, samples could only be taken from the lower part. The colour palette is quite limited and includes white, yellow, red, blue, and black. White lime was used extensively, especially for the tinted light background, which is greyish-ochre in tone, so it is probably mixed with yellow earth or some organic black pigment. Raman spectrography identified yellow goethite and red hematite, the former being among the most commonly used pigments in this mural. The cross-sections confirm the use of azurite, which can be identified by its characteristic colour and the shape of the angular grains resulting from the crushing of this mineral (Fig. 2). Azurite was also identified by chemical analysis. It was applied directly on the plaster, which is unusual, as most Slovenian mural paintings feature a grey or red-brown underpainting. The question of the choice of pigments arises in the case of the dark flowers in the background, Mary’s black tunic and halo, the dark cloak of St John the Evangelist, and the blood of Christ pouring from his wounds. It appears that a lead pigment was used, which has eventually darkened due to chemical reactions (Fig. 1). Raman spectroscopy has confirmed the presence of platnerite, resulting from the degradation of lead white or minium due to the oxidants in the atmosphere or microbiological action. Thus, the flowers and Mary’s mantle could have originally been red or white, which is surprising, as her mantle is otherwise symbolically blue. The black pigment used for the contours is probably of organic origin. The basic binder is lime, though an organic binder of sorts (egg tempera, animal glue or casein) was probably also used for the azurite and the additions, such as the flowers in the background.

The mural was painted using a combination of al fresco and al secco techniques, and limewash may also have been used in some cases. The final additions, which were applied dry, have mostly fallen off, and the flowers in the background were most likely stamped in this manner as well.

Much of the painting was outlined with thin incised lines, suggesting the use of a template for the figures. We can thus discern thin, shallow, and barely visible incisions for the upper pointed bordure, the cross, and a double line for the round halos. The figures of Mary and St John the Evangelist were incised as well, as in some places, we can make out thin lines indicating the figure’s edging, parts of the drapery such as the folds of the mantle, and some other drapery folds. Nevertheless, a red underdrawing was also used, especially for the body of Christ. It can be seen, for example, on Christ’s left hand or on the lower edge of the INRI inscription band (Fig. 3). The underdrawing is mostly covered by layers of colour and a black final contour. The basic colour layers were applied as primary colour tones. An underpainting was used for the entire Mary’s halo; in some places, a red colour layer shows from under the black layer. Originally, the halo was probably yellow and painted with lead yellow, which has eventually blackened. The draperies still feature a bit of modelling, especially shading and highlighting of the folds that once created volume. Only Christ’s white tunic was designed with only black lines for the folds. The figures are elegant, slender, and presented in a three-quarter profile. The faces are round and very precisely shaped. The painter’s work around the eyes, placed under semicircular eyebrows, was meticulous (Fig. 3). He used a thicker black stroke for the upper line of the eyelid, a thinner one for the lower line, and placed an elongated but not particularly large eye between them. A small nose with semicircular nostrils protrudes from the inner eyebrow. The mouth is fleshy, and the lips are divided by a black horizontal line. The same design was used for all three figures, while Christ is the only one whose eyes are closed. His entire body features an even black contour, emphasising his chest and ribs. The carnation of the faces is pink, though this layer of colour has barely been preserved. The hair of both male figures is ochre and modelled with broad dark brown streaks to create waves and curls. The hands of all three figures are elegant, featuring long fingers and various positions, though they are disproportionately large. The same is true of the bare feet (St John the Evangelist), which appear spatula-like. The colour modelling of the carnations has not been preserved. The flowers filling the bright background were probably made using a stamp, while a stencil may have been used for the heart-shaped tendril decorating the upper bordure.

Muta, Succursal church of St Peter, Stage 1 (Muta, succursal church of St Peter), 2024 (last updated 6. 9. 2024). Corpus picturarum muralium medii aevi, https://corpuspicturarum.zrc-sazu.si/en/poslikava/phase-1-muta-succursal-church-of-st-peter/ (9. 7. 2025).

Legal Terms of Use

© 2025 ZRC SAZU UIFS, Corpus picturarum muralium medii aevi

ZRC SAZU

France Stele Institute of Art History

Novi trg 2

1000 Ljubljana

Spodaj seznam podrobno opisuje piškotke, ki se uporabljajo na našem spletnem mestu.

| Cookie | Type | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| _ga | Non-Necessary | 2 years | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. The cookie is used to calculate visitor, session, camapign data and keep track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookies store information anonymously and assigns a randoly generated number to identify unique visitors. |

| _gat | Non-Necessary | 1 minute | Google uses this cookie to distinguish users. |

| _gid | Non-Necessary | 1 day | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. The cookie is used to store information of how visitors use a website and helps in creating an analytics report of how the wbsite is doing. The data collected including the number visitors, the source where they have come from, and the pages viisted in an anonymous form. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | Necessary | 1 year | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-non-necessary | Necessary | 1 year | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Non Necessary". |

| CookieLawInfoConsent | Necessary | 1 year | The cookie is used to store the summary of the consent given for cookie usage. It does not store any personal data. |

| PHPSESSID | session | Time of session | Cookie stores information about the user's session and allow users to keep their entries during the time of visiting the website. |

| pll_language | Necessary | 1 year | This cookie is used to remember any selection a user has made about language. |

| show_preloader_once | Necessary | Session | With this cookie we remember the user's first visit. |

| viewed_cookie_policy | Necessary | 1 year | The cookie is used to store whether or not you have consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |