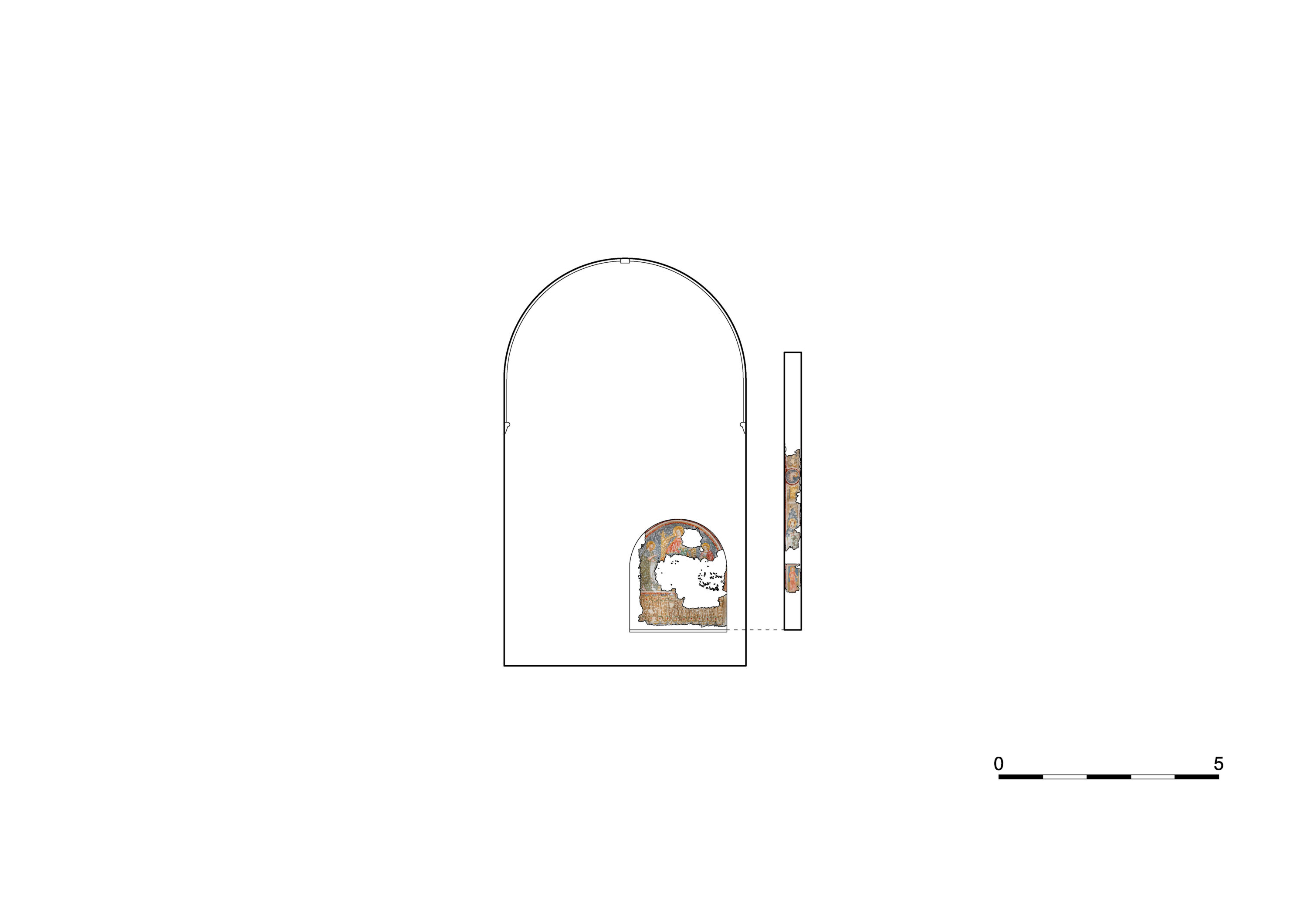

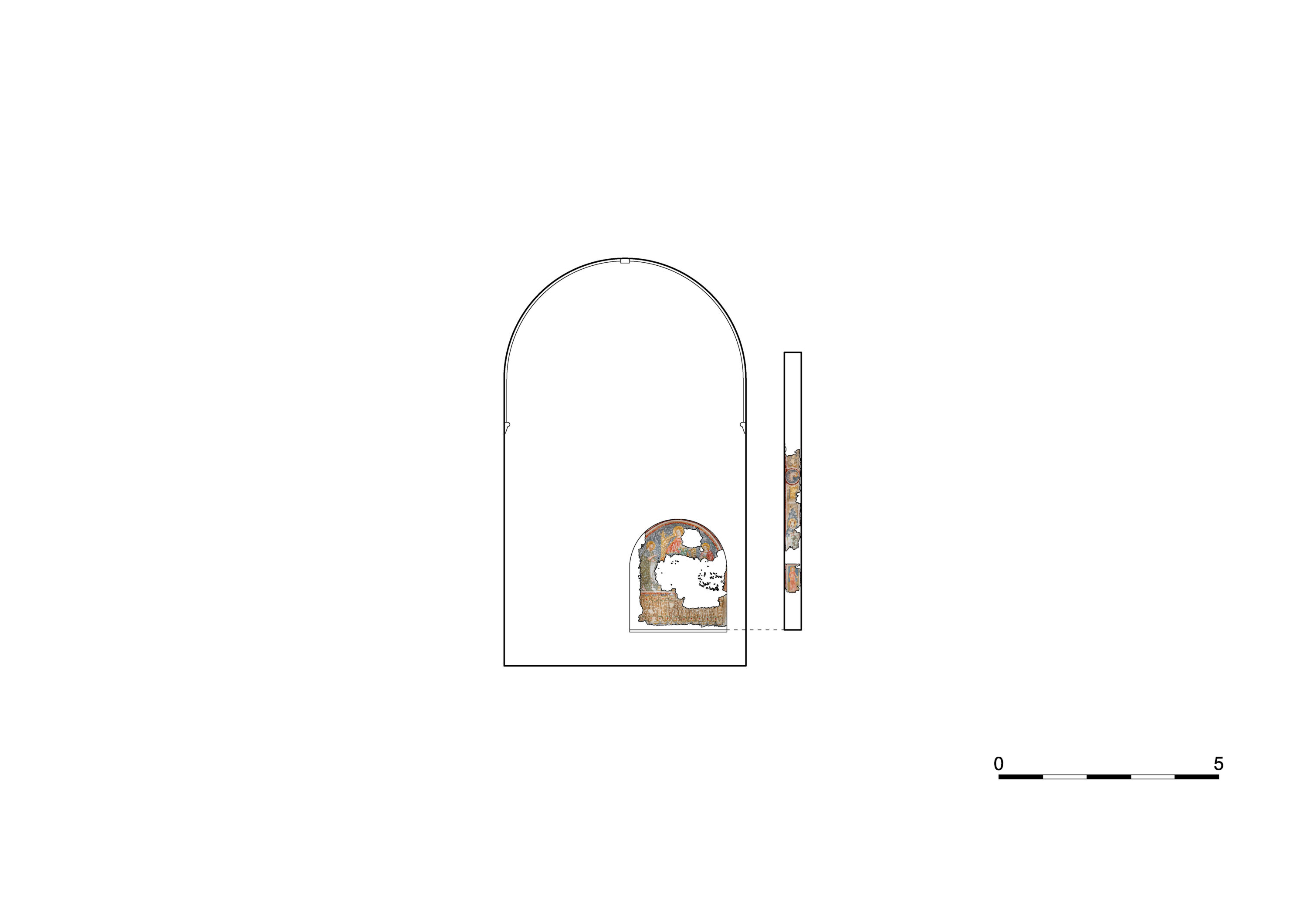

A fresco in a niche in the northern wall of the chancel, depicts Mary and the Child on a throne with St John the Baptist and St John the Evangelist with their attributes, the unrolled scroll and a book. The bottom part of the fresco features a decorative curtain, while the two saintly figures are portrayed one below the other on the right-hand border of the niche. The female figure below is depicted with three crowns (two in her hands and the third one on her head), while the saint above her has no visible attributes. The upper saint is portrayed in the (architecturally) triple broken Gothic niche, continuing into the architecture with two towers. At the top, a lamb is depicted in the centre of the niche’s border.

Medium.

The fact that only fragments of the figures’ faces have been preserved impedes a more precise stylistic analysis. The soft modelling of the carnation, their green underpainting, the thickly applied layers of paint, the way the highlights are rendered, the voluminousness of the lead white, and the thin dark lines used to draw the hair and beards of the saints suggest the Byzantine tradition and point us towards the painting of the Venetian Lagoon.[1] The mural also features the Trecento elements that Giotto introduced in Padua and, by extension, in the broader Venetian sphere of influence at the beginning of the 14th century. Apart from the colour pigments (carbon black, green earth, red and yellow ochre, calcite, azurite),[2] this is also indicated by the gilded ray halos incised into the plaster; the type of dress that Mary and the female saint on the right edge of the niche are wearing[3] (with a belt cut below the breasts and a collar fastened at the neck); and the design of the throne with a semi-circular backrest and the backrest’s upper edge ornamentation consisting of ball-shaped decorative elements. The connection with Venice is also suggested by the particular architectural features, such as the triple broken pointed Gothic niche in which St John the Baptist stands. This type of niche can be found in the Porta dei Fiori portal of St Mark’s Basilica in Venice[4] or on the main façade of the Church of San Fermo in Verona.[5] The architectural model of Mary’s throne with its semi-circular backrest also appears in many iconographically related scenes depicted in the murals in the churches of San Zeno and San Fermo in Verona. In the latter, its sculpted version is also repeated on the tombstone of Aventino Fracastoro on the façade.[6] An important example is the throne in the panel painting The Mystic Marriage of St Catherine with Saints by an anonymous master called Maestro del paliotto delle Sette Santi, kept in Museo di Castelvecchio museum in Verona.[7] An important element that can contribute to the dating of the Koper fresco is the type of dress worn by the female sainton the right edge of the niche and by Mary, with the collar closed up to the neck and a high belt cut below the breasts, suggesting that the painting was made in the first quarter of the 14th centuryor perhaps in the early 1330s.[8]

________________________________________

[1] The painting style of the master from Koper seems to be close to the stylistic trend that emerged in Venice sometime between 1310 and 1315 (probably based on the new wave of Byzantine painting of the Palaiologos period), which again leaned towards a more consistent depiction of space and the use of classical architectural and decorative elements. This stylistic orientation can be identified in the works by the author of the Trieste triptych of St Clare and in those by the artist referred to as Master of Virgin Mary’s Coronation (Maestro del Incoronazione della Vergine) after a panel painting from 1324, which is kept at the National Gallery of Art in Washington (Cristina GUARNIERI, Il passaggio tra due generazioni: dal Maestro dell’Incoronazione a Paolo Veneziano, Il secolo di Giotto nel Veneto (edd. Giovanna Valenzano, Federica Toniolo), Venezia 2007, p. 154, n. 4). Based on the soft modelling of the carnation, the thickly applied layers of paint, the way the highlights are rendered, and the voluminousness of the lead white (the outlined wrinkles on the forehead and cheeks, the shaping of the hands, the neck, and the drapery), the Koper fresco could be likened to the frescoes in the Venetian Church of San Zan Degolà, which Cristina Guarnieri attributed to the Master of Virgin Mary’s Coronation, although in San Zan Degolà, the master was much more committed to the Byzantine tradition and probably also belonged to an older generation. For the newest research on Venetian painting at the turn from the 13th to the 14th century, see especially Cristina GUARNIERI, Il passaggio tra due generazioni: dal Maestro dell’Incoronazione a Paolo Veneziano, Il secolo di Giotto nel Veneto (edd. Giovanna Valenzano, Federica Toniolo), Venezia 2007, pp. 153–201.

[2] For natural science research, see GUTMAN LEVSTIK, MLADENOVIČ, KRIŽNAR, KRAMAR 2019, pp. 95–104.

[3] At first glance, the female saint on the right edge of the niche appears to be stylistically different and of poorer quality than the other figures. However, this is probably due to the fact that this part of the painting is not as well preserved, so the final modelling and details are no longer visible. Otherwise, the pigments used in the depiction of the saintess are identical as elsewhere in the mural, the halos are depicted equally as in the other figures, and the carnation modelling in the best-preserved areas of the mural (e.g. on the neck of the figure) is the same as well.

[4] Cf. Fulvio ZULIANI, Conservazione ed innovazione nel lessico architettonico veneziano del XIII e XIV secolo, Architettura gotica Veneziana (edd. Francesco Valcanover, Wolfgang Wolters), Venezia 2000, p. 33.

[5] For the Church of San Fermo, see especially I Santi Fermo e Rustico. Un culto e una chiesa in Verona (edd. Paolo Golinelli, Caterina Gemma Brenzoni), Verona 2004.

[6] See GUTMAN LEVSTIK, MLADENOVIČ, KRIŽNAR, KRAMAR 2019, pp. 95–104.

[7] Il Trecento. La pittura nel Veneto (ed. Mauro Lucco), 2, Milano 1992, p. 362.

[8] In his basic study, Luciano Bellosi, the pioneer of researching the 14th-century Italian dress culture based on painting, discovered, among other things, that the neckline of women’s dresses in the 14th century in Italy was an important dating indicator. At the beginning of the century, the collars of women’s dresses reached all the way to the neck, like in the examples of the dresses of the female figures painted by Giotto in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua. Towards the middle of the century, the necklines gradually became broader, reaching the shoulders in the second half of the century and later even falling below the shoulders. More about this in Luciano BELLOSI, Moda e cronologia. B) Per la pittura di primo Trecento, Prospettiva, 11, 1977, pp. 12–27.

Between 1320 and 1330.

Venetian master.

In the niche, the iconographic motif of Mary and the Child on the Throne with St John the Baptist and St John the Evangelist is depicted. John the Evangelist holds a book, while John the Baptist holds a scroll with a fragment of an inscription in Gothic script. The individual letters that are still visible suggest that it once bore the canonical inscription EGO VOX CLAMANTIS IN DESERTO.[1] The figures of Mary and the Child are depicted in an archaic frontal type, that is far less common in the 14th-century Italian painting than, for example, the Hodegetria and Eleousa types.[2] The iconographic motif of Christ giving blessings with both hands is derived from the Platytera iconographic type[3] – except that Mary is not depicted as an orant in this case. This type of representation is still quite common in the 14th-century Venetian painting; it can be found for example in the relief on the lunette of the portal to the belfry of the Basilica of Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari and in a fresco in the same church, depicted on the outer wall of the left transept of Cappella dei Milanesi (Chapel of the Milanese).[4] Another example is the mid-14th-century panel painting Madonna della Misericordia from a private collection, formerly attributed to Paolo Veneziano, or Jesus in a mandorla in the panel painting Madonna Platytera with St Peter, St John the Baptist, and St John the Evangelist in the Scuola Grande di San Giovanni Evangelista, signed “Franciscus”.[5] In Koper, two other saintly figures are portrayed on the right edge of the niche. The female figure below is probably St Elizabeth of Hungary with three crowns (two in her hands and the third one on her head),[6] while the saint above her has no visible attributes and cannot be identified for now. The saint stands beneath a triple broken pointed arch, which continues into a tower or architecture with two towers. The Agnus Dei motif is depicted in the centre.[7] The layout with two saints and the same architectural design that is still partially visible was probably repeated on the left edge, but that part of the mural has not been preserved.

________________________________________

[1] The phrase is taken from the Gospel of John (Jn 1:22-23). For more information about the iconographic types of St John the Baptist, see Elisabeth WEISS, Johannes der Täufer (Baptista), Lexikon der christlichen Ikonographie, 7, Rom-Freiburg-Basel-Wien 1994, coll. 164–190.

[2] For the Hodegetria iconographic type, see Horst HALLENSLEBEN, Das Marienbild der byzantinisch-ostkirchlichen Kunst nach dem Bildstreit, Lexikon der christlichen Ikonographie, 3, Rom-Freiburg-Basel-Wien 1994, coll. 168–170. For the Eleusa or Glykophilusa type, see Horst HALLENSLEBEN, Das Marienbild der byzantinisch-ostkirchlichen Kunst nach dem Bildstreit, Lexikon der christlichen Ikonographie, 3, Rom-Freiburg-Basel-Wien 1994, coll. 170–172.

[3] For the Platytera iconographic type, see Horst HALLENSLEBEN, Das Marienbild der byzantinisch-ostkirchlichen Kunst nach dem Bildstreit, Lexikon der christlichen Ikonographie, 3, Rom-Freiburg-Basel-Wien 1994, coll. 167–168.

[4] Cf. Annalisa BRISTOT, Gli affreschi esterni di Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari, L’architettura gotica veneziana (edd. Francesco Valcanover, Wolfgang Wolters), Venezia 2000, pp. 189–194.

[5] For more examples, see Annalisa BRISTOT, Gli affreschi esterni di Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari, L’architettura gotica veneziana (edd. Francesco Valcanover, Wolfgang Wolters), Venezia 2000, pp. 189–194.

[6] For the iconography of Elisabeth of Hungary, see Karin HAHN, F. WERNER, Elisabeth von Thüringen, Lexikon der christlichen Ikonographie, 6, Rom-Freiburg-Basel-Wien 1994, coll. 133–140.

[7] For the iconography of the Agnus Dei motif, see Redaktion, Lamm. Lamm Gottes, Lexikon der christlichen Ikonographie, 3, Rom-Freiburg-Basel-Wien 1994, coll. 7–14.

Pigments: white lime (calcite), yellow ochre (goethite), red earth (haematite), green earth (celadonite), azurite, carbon black, gold

Analytical techniques: OM, Raman, SEM-EDX

The mural is painted on two layers of plaster, arriccio (rough plaster) and intonaco (smooth plaster). The upper layer is about 1.5 cm thick, while the sample of the lower layer measures only 9 mm, though the plaster layer itself is undoubtedly thicker. The cross-sections of the samples only include the upper layer of plaster, which appears saturated with the aggregate consisting of differently sized and varicoloured angular grains (Fig. 1). The grains are translucent or coloured (yellow, red, or brown). Judging from the angular shapes of the grains, this is crushed sand. Numerous lumps of lime can be detected in the plaster, indicating that the binder and the aggregate were not sufficiently mixed, while the lime was not rested well enough. The petrographic-mineralogical analysis of the thin slices of the two layers reveals that their composition is very similar and that they, therefore, belong to a single mural. Both samples contain lime as the binder, which is more abundant in the top layer than in the bottom one. The aggregate of both layers consists mostly of silicate grains, mainly quartz, and a more modest amount of carbonate grains (the quantity of the latter is even smaller in the arriccio). The arriccio contains slightly more aggregate than the intonaco, with grain sizes averaging up to 0.21 mm, while the intonaco contains slightly smaller grains, measuring up to 0.16 mm. Rare grains of biogenic foraminifera are also discernible in both layers.[1]

________________________________________

[1] Maja GUTMAN, Poročilo naravoslovnih preiskav. Cerkev sv. Frančiška Asiškega, Koper (EŠD 8345). Analiza barvnih plasti in ometov dveh stenskih poslikav, Restavratorski center, Ljubljana, 2015 (typescript). See also GUTMAN LEVSTIK, MLADENOVIČ, KRIŽNAR, KRAMAR 2019, pp. 95–104.

The colour palette is rich and includes white, ochre, red, burgundy, purple, blue, green, brown, grey, and black colours. Using a combination of the SEM-EDX and Raman techniques, we have identified almost all the pigments and most of their mixtures. The white is white lime (calcite), while the yellow is yellow ochre (goethite). The red pigment used for the decorative band, the burgundy curtain, and St John the Evangelist’s cloak is red earth (haematite), while haematite mixed with carbon black was used to obtain the ochre colour of the Throne of Mary. Haematite was also used for the brown curtain. The purple-blue tunic of St John the Baptist was painted using a mixture of carbon black and red and yellow ochre. For the main scene’s blue background colour, azurite was used, which can also be identified in the cross-sections based on the angular grains of the crushed mineral (Fig. 2). In secondary spots such as the jambs, the blue colour was obtained by applying a mixture of white lime and carbon black on a red underpainting (Fig. 3). The green colour is green earth (celadonite), which the painter used for the green tunic of Jesus and for the decorative band. Meanwhile, the darker colour of St John the Baptist’s cloak was obtained by mixing green earth with yellow and red ochre (Fig. 4). The black decorative band was painted with carbon black. The halos were gilded, and the gold was applied to a thin layer of haematite (Fig. 5). The main binder is lime from the plaster, though some organic binder was also used, which has not been analysed due to a subsequent consolidation of the mural.[1]

________________________________________

[1] Maja GUTMAN, Poročilo naravoslovnih preiskav. Cerkev sv. Frančiška Asiškega, Koper (EŠD 8345). Analiza barvnih plasti in ometov dveh stenskih poslikav, Restavratorski center, Ljubljana, 2015 (typescript).

The mural was created using a combination of painting on fresh plaster (al fresco) (Figs. 1, 3 – layer 2) and on an already dry base (al secco) (Figs. 1, 3 – layer 3, Fig. 5). As it is evident from the cross-sections, much of the painting was finished on the already dry plaster, with many samples showing a clear division between the plaster and the colour layer or between the individual colour layers.[1]

________________________________________

[1] Maja GUTMAN, Poročilo naravoslovnih preiskav. Cerkev sv. Frančiška Asiškega, Koper (EŠD 8345). Analiza barvnih plasti in ometov dveh stenskih poslikav, Restavratorski center, Ljubljana, 2015 (typescript).

In the lower part of the mural, where the intonaco is missing, we can see a horizontal red line that can be considered a sinopia, i.e. a preparatory drawing on the lower plaster layer (Fig. 6). There are also some dark grey strokes around it, but it is not clear if they are also part of the sinopia. These features are part of the painting procedure characteristic of Italian Trecento painting, which the painter used as guidance before applying the intonaco. The halos and the outlines of the heads are incised into the intonaco with a thin, barely perceptible line, while the halos are decorated with thin ray-shaped pouncings pressed into the plaster. The circle around the lamb on the vault of the niche may have been incised as well, but the potential incisions were covered with colour layers. No underdrawing can be seen anywhere clearly, as the painter covered it very well with subsequent colour applications. It could have been applied in red, as on the upper part of the scroll held by St John the Baptist, it is still possible to discern red lines under the white colour (Fig. 7), though these may also only be a slight shading of the scroll. The blue azurite was applied directly on the plaster (Fig. 2) without any underpainting underneath. No underpainting was detected anywhere else, either. For the draperies, the throne, and the background, the painter therefore used local tones, on which he also based the modelling of the light and the shades. He strived to create soft colour transitions by using several tones of the same colour but did not always succeed, as he mostly modelled with a brush a centimetre thick. While the faces of both the male and female saints are elongated, the heads of Mary, Jesus and St John the Evangelist are more rounded, conveying a certain gracefulness. Most of the faces have been notably damaged. However, it is still possible to make out the relatively small eyes, further defined by the upper eyelids outlined with dark-ochre lines, which the painter also used to apply shading to the space between the eyelids and the eyebrows. Lastly, he drew a final contour around the eyes and the eyebrows with a warm brown colour. The eyebrows are only slightly curved and follow the line of the eyelid. A long, straight nose, shaded only on the inside, continues from the eyebrows. Together with the nostrils, it ends in a clover-like shape. The mouth is large and fleshy. The upper lip features prominent central peaks; the lower lip is indicated with a shorter line; and there is a strong brown line between the two. Originally, the mouth was bright red, which can still be seen in the figures of Mary and St John the Baptist. The carnation is a basic pink, modelled with strong white and darker pink and ochre layers. On the forehead, the painter created parallel horizontal wrinkles with alternating strokes in white, pink, and ochre colours. He used similar intense applications to model the cheekbones and the neck, especially on St John the Baptist and the saint on the vault above the niche. In Mary, Jesus, and St John the Evangelist, the pink cheeks and generally lighter complexion stand out, which the painter also modelled with a greyish colour applied along the nose, around the mouth, on the temples, on the nose ridge, and especially at the transition between the jaw and the neck. He finished the faces with a warm red contour. The hair is painted with precision, as the painter outlined the strands with thin parallel lines drawn in the chosen base colour (ochre, dark brown). The hands are elegant, with narrow but not excessively long fingers that look remarkably natural. The carnation is also pink, modelled in darker ochre and pink tones, with intense highlights applied to the back of the hands to highlight the tendons. The bare hands feature an entire range of colours, from dark red for the shadows to almost white in the brightest parts, as can be seen perfectly on the Baptist’s right hand (Fig. 7). Meanwhile, Jesus’ hands were painted in the same manner as his face: thus, they are lighter in colour and shaded with light grey, pink, and ochre. The painter also used several colour tones for the draperies, where he created soft transitions between the shadows and light. In this regard, the cloak of the saint on the vault is particularly interesting, as the painter shaded the pink colour with green and finished the cloak by applying white highlights to the top of the folds and red-brown strokes for the deepest shadows. The importance of colours and soft modelling is also obvious in the case of the final contours, which are mostly painted in the dark colours of the draperies or carnations rather than being a generic black contour which would give the mural a more linear look, as is typical of the northern painting tradition. The halos are gilded, and the gold was applied to a red layer (probably bole), which serves as a base for smoothing the gold foils. The Throne of Mary is presented three-dimensionally, thus opening up the space for the figures. The painter left the parts closer to the viewer brighter while shading the more distant areas, creating an illusion of a light source illuminating the throne from the front. He also softly modelled the spheres at the top of the throne. The curtain under the scene was painted similarly as the figures’ draperies: using a broad brush, the painter applied several tones of darker ochre shading on the base colour, probably ochre; accentuated the tops of the folds with strong white highlights; and then outlined the darkest shadows with a dark-brown contour. Despite the predominance of relatively broad strokes, the painter managed to create a fairly good soft tonal transition, attesting to his considerable skill.

Koper, Monastery and Church of St Francis, Stage 1 (Koper, Monastery and Church of St Francis), 2024 (last updated 7. 1. 2025). Corpus picturarum muralium medii aevi, https://corpuspicturarum.zrc-sazu.si/en/poslikava/phase-1-koper/ (27. 8. 2025).

Legal Terms of Use

© 2025 ZRC SAZU UIFS, Corpus picturarum muralium medii aevi

ZRC SAZU

France Stele Institute of Art History

Novi trg 2

1000 Ljubljana

Spodaj seznam podrobno opisuje piškotke, ki se uporabljajo na našem spletnem mestu.

| Cookie | Type | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| _ga | Non-Necessary | 2 years | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. The cookie is used to calculate visitor, session, camapign data and keep track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookies store information anonymously and assigns a randoly generated number to identify unique visitors. |

| _gat | Non-Necessary | 1 minute | Google uses this cookie to distinguish users. |

| _gid | Non-Necessary | 1 day | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. The cookie is used to store information of how visitors use a website and helps in creating an analytics report of how the wbsite is doing. The data collected including the number visitors, the source where they have come from, and the pages viisted in an anonymous form. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | Necessary | 1 year | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-non-necessary | Necessary | 1 year | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Non Necessary". |

| CookieLawInfoConsent | Necessary | 1 year | The cookie is used to store the summary of the consent given for cookie usage. It does not store any personal data. |

| PHPSESSID | session | Time of session | Cookie stores information about the user's session and allow users to keep their entries during the time of visiting the website. |

| pll_language | Necessary | 1 year | This cookie is used to remember any selection a user has made about language. |

| show_preloader_once | Necessary | Session | With this cookie we remember the user's first visit. |

| viewed_cookie_policy | Necessary | 1 year | The cookie is used to store whether or not you have consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |