Originally, the otherwise only partially preserved mural covered all the walls of the chancel, the vault, and the underside of the triumphal arch.[1] The vault features a depiction of Christ Pantocrator and the symbols of the evangelists. The western bay bears an image of Christ Pantocrator, sitting on a simple throne. He probably bestowed blessings with his right hand and held a book in his left. His face with a short cleft beard stands out in terms of preservation.[2] The four symbols of the evangelists are arranged in the remaining bays. Matthew’s angel, wearing a diamond-patterned robe, is still visible in the bay above the northern wall,[3] while Luke’s ox is in the north-eastern bay.[4] The south-eastern bay probably contained Mark’s lion,[5] while John’s eagle was painted in the southern one. The depictions of the evangelists’ symbols included larger inscription bands, while in the lower part, the symbols were placed on a decorative bordure consisting of discs.[6]

The entire available northern wall surface is covered with a depiction of the Death of Mary. The lower part features a bed with the dying Virgin Mary lying on it, with the mourning apostles behind her. Most of them are painted during prayer, but some stand out due to their gesticulation. In the upper part of the composition, in the area on the wall beneath the vault, Christ is depicted in a mandorla, carried by two kneeling angels. The soul of Mary in the form of a little girl is in Christ’s arms.[7]

A monumental depiction of a female saint wearing a mantle, which has been partially destroyed due to the construction of a secondary window, is painted on the chancel’s opposite southern wall. The portrayed woman is either St Agnes or Mary,[8] with the faithful huddled under the mantle. The crowned female figure with long, light-coloured curly hair is placed in the centre of the wall. Her cloak is decorated with a palmette containing tendrils, shaped like a lyre, while the underside features an ermine lining.[9] Two groups of worshippers are painted under the mantle.[10] Clerics or church dignitaries are depicted on the left, while lay persons are on the right, with members of the nobility also recognisable among them.[11] Both the Death of Mary scene and the saintess with the mantle are surrounded by a bordure consisting of a folded ribbon.[12]

The two diagonal walls that conclude the chancel were originally decorated with depictions of four female saints,[13] of which only the central two have been preserved in their entirety due to the subsequent enlargement of the window openings. In the eastern corner of the termination, St Margaret is visible on the left, while St Agnes is on the right. The two saintesses are painted as slender full-length figures, facing each other in a three-quarter profile. They are depicted with five-leaf crowns and long wavy hair with braids falling on their bare shoulders. They are wearing tight-fitting fashionable clothes.[14] St Margaret has a dragon at her feet, while St Agnes holds a lamb in her right hand. Above the two saintesses, on the upper edge of the rectangular frame, are two poorly preserved Latin inscriptions with their names.[15] The fact that the area of the wall beneath the vault above the saintesses was decorated with the moon and the sun is evident from the preserved depiction of the moon on the north-eastern side of the chancel.

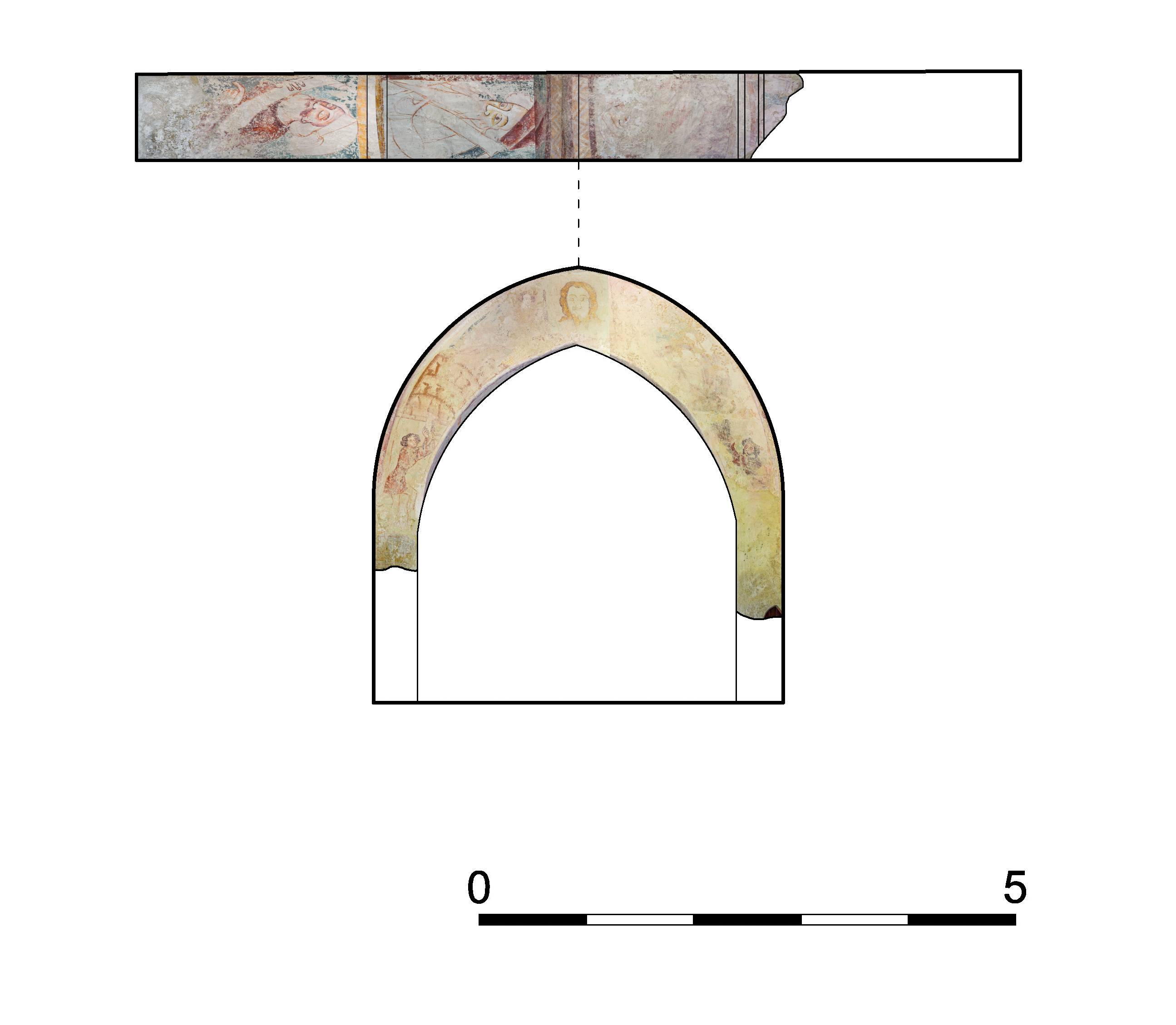

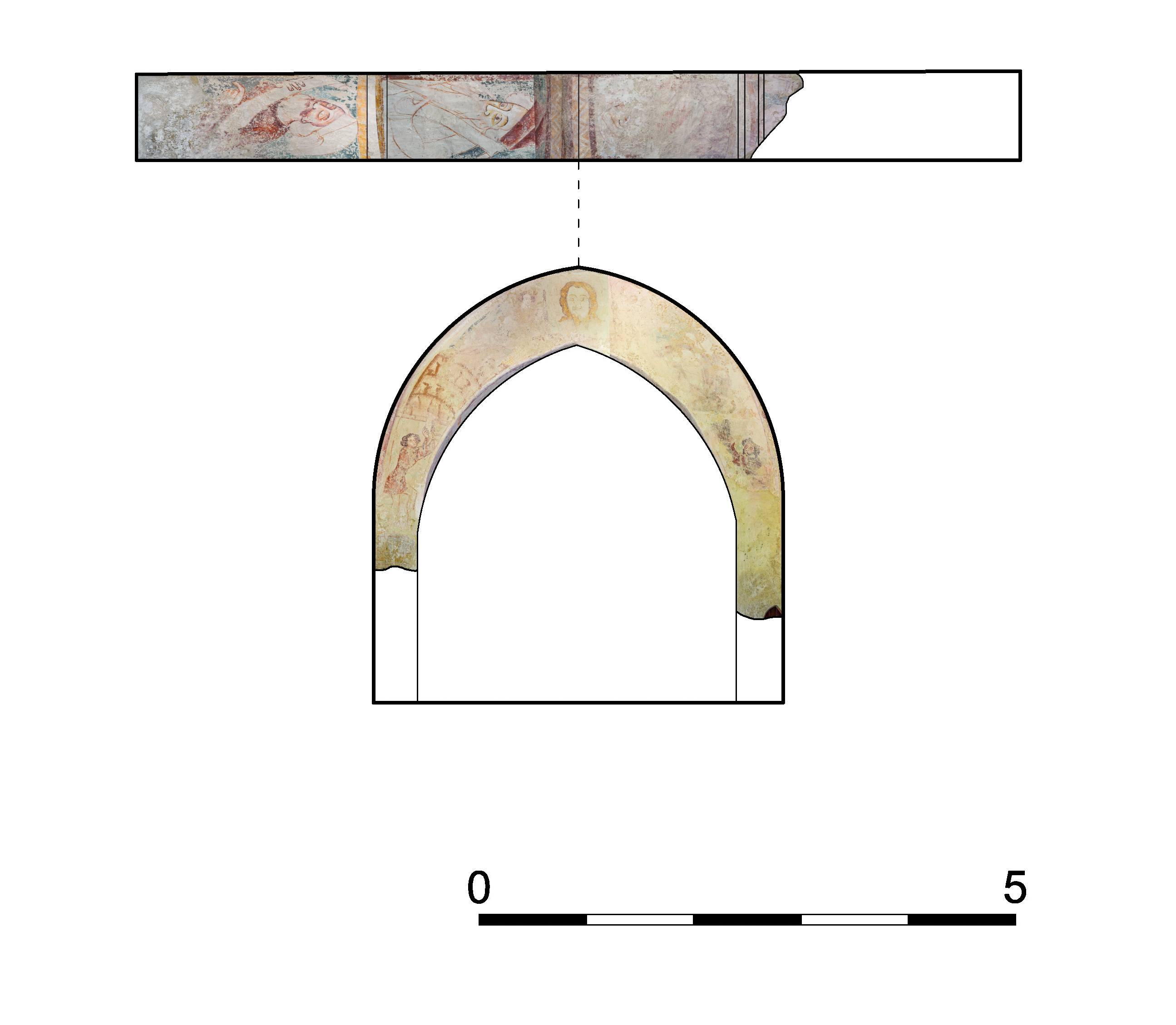

The lower part of the interior side of the triumphal arch bears the depiction of Abel offering a lamb on the left and Cain with a sheaf of grain on the right. Above them, the face of Christ is painted in the centre, flanked by two angels with a candle. Two of the original four prophets have been preserved on the underside of the arch.[16] The southern part of the arch features rectangular frames with half-length depictions of two bearded men in a three-quarter profile, looking towards the interior of the chancel. Both are wearing head coverings and holding inscription bands. The halos, painted crowns, and outlines of faces were either incised or pressed into the fresh plaster.[17]

________________________________________

[1] GREGOROVIČ 1993, p. 42.

[2] ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 101.

[3] ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 101; HÖFLER 2004, p. 84.

[4] GREGOROVIČ 1993, p. 44 (like ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 101), incorrectly states that this bay contains a depiction of John’s eagle.

[5] ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 101.

[6] HÖFLER 2004, p. 85.

[7] Cf. MENAŠE 1994, p. 266; ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 99; HÖFLER 2004, p. 85.

[8] KOVAČIČ 1984, p. 307; ŠPITALAR 1986, pp. 23–25; HÖFLER 2004, p. 85; and KRIŽNAR 2006, p. 123, identified the saintess as St Agnes. On the other hand, GREGOROVIČ 1993, p. 43 (like ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 100), believes that this is a portrayal of the Virgin of Mercy with the mantle. See the Iconographic Analysis section.

[9] GREGOROVIČ 1993, p. 43; ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 101; HÖFLER 2004, p. 85.

[10] HÖFLER 2004, p. 85.

[11] GREGOROVIČ 1993, pp. 43–44; ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 101; HÖFLER 2004, p. 85.

[12] HÖFLER 2004, p. 85.

[13] HÖFLER 2004, p. 84. John Höfler identified the destroyed saintess on the left side of the north-eastern diagonal wall as Mary Magdalene.

[14] GREGOROVIČ 1993, p. 44.

[15] GREGOROVIČ 1993, p. 44; HÖFLER 2004, p. 84.

[16] HÖFLER 2004, p. 84.

[17] KRIŽNAR 2006, p. 124.

The mural in the chancel has only been partially preserved, mainly due to the 19th-century alterations. The scenes on the chancel’s diagonal walls and on the southern and northern walls have been partially destroyed.[1] The colour layer on the vault has been poorly preserved.[2] During the uncovering, the murals were already in a very poor condition.[3]

________________________________________

[1] Cf. GREGOROVIČ 1993, p. 42.

[2] Cf. KRIŽNAR 2006, p. 123.

[3] KOVAČIČ 1984, p. 307.

The mural belongs to the so-called transitional or mixed style of the second half or the last third of the 14th century, typical of Eastern Alpine painting.[1] This style is characterised by the diminishing northern influences and the increasing influences of Italian art.[2] The mural in the church of St Agnes combines Italian influences and characteristics of the High Gothic linear style at an exceedingly folk level,[3] with the drawing style overpowered by the Italian influences.[4] The new influences resulted in a greater degree of realism, volume modelling, and epic narration, which, according to Tanja Zimmermann, can also be found in the murals in the church of St Nicholas in Koritno above Čadram and in the church of St Nicholas in Pangrč Grm.[5] The mural in the church in Vrhe is the first example of this stylistic orientation in the territory of today’s Slovenia, though it is not the only one.[6]

________________________________________

[1] ZIMMERMANN 1996, pp. 102–103; HÖFLER 2004, p. 85; KRIŽNAR 2006, p. 64; JAVORNIK 2008, pp. 188–189. The concept of the mixed or transitional style was defined by Tanja Zimmermann; see ZIMMERMANN 1996.

[2] HÖFLER 2004, p. 85.

[3] ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 102; HÖFLER 2004, p. 85.

[4] ZIMMERMANN 1995, p. 222.

[5] ZIMMERMANN 1996, pp. 65, 144–145.

[6] HÖFLER 2004, pp. 14–16.

The mural has been dated to around 1370.[1]

________________________________________

[1] ŠPITALAR 1986, p. 28; GREGOROVIČ 1993, p. 42; HÖFLER 2004, p. 86; KRIŽNAR 2006, p. 64. In her doctoral dissertation, ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 102, gives a somewhat broader dating to the period between 1370 and 1380. The 1367 permission to construct the church represents the terminus post quem for the creation of the mural. For more information about this, see the Historical Information section. The question of when the church’s construction began and when it was painted remains open – perhaps as early as 1370, or not until a few years later.

The murals on the vault and triumphal arch (Christ Pantocrator, the evangelists’ symbols, the prophets, Cain and Abel) adhere to a common and widespread iconographic programme.[1] This system of murals started to develop after the middle of the 14th century and gradually led to the scheme of the so-called Carniolan Presbytery.[2] The Death of Mary scene is an iconographic type that combines the death of Mary with her Assumption, and in which Christ and Mary’s souls are portrayed as a heavenly pair.[3] This combined iconographic type replaces the Coronation of Mary scene, which is usually the final scene of the Marian cycles in the northern art of the first half of the 14th century.[4] Until now, the interpretation of the mural on the southern wall of the chancel in the relevant literature has varied. The explanation has eventually prevailed that the saintess with the open mantle represents the church’s patron saint, St Agnes.[5] Nevertheless, the identification remains open, and the arrangement of the ecclesiastical and secular figures under the mantle, which are already separated into two groups, is more characteristic of the portrayals of the Virgin of Mercy with the mantle.[6] However, this motif would be better related to the depiction of the Death of Mary on the north wall of the chancel.

________________________________________

[1] HÖFLER 2004, p. 84.

[2] ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 154.

[3] ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 99.

[4] ZIMMERMANN 1996, pp. 99–100.

[5] Cf. KOVAČIČ 1984, p. 307; ŠPITALAR 1986, pp. 23–25; HÖFLER 2004, p. 85 (with further references). Supposedly, the head is more reminiscent of St Agnes than the Mother of God.

[6] Tanja Zimmerman also identified the portrayal as the Virgin of Mercy with the mantle; see GREGOROVIČ 1993, p. 43; ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 100. Ana Lavrič (LAVRIČ 2015, p. 484) notes that the mantle’s ermine lining is typical of the depictions of St Ursula, while the separate depiction of two groups under Mary’s mantle only became established in the 15th century in the Mater omnium type. Saints typically only shelter certain groups of people, such as confraternities. Cf. HÖFLER 2004, p. 85.

Pigments: white lime, yellow and red earth, cinnabar, carbon black

Analytical techniques: OM, SEM-EDX, XRD, FTIR

The mural is painted on a single layer of plaster, which is relatively thin, between two and four millimetres. The plaster is very solid and compact, applied on top of an older, well-smoothed plaster, which had already been painted with some kind of ornaments before the mural in question. The older layer of plaster had been hammered all over the surface before the new plaster was applied to ensure it adhered better. The sand grains are fine and the plaster was thoroughly mixed, though a few tiny lumps of lime can still be found in places. The plaster’s composition can be seen in more detail in the cross-sections of the samples taken (figs. 1–2), confirming that the binder and filler were very well blended and that the workshop mostly used fine-ground sand of a very light colour. Larger grains also occur occasionally, some of them darker and elongated, flattened in shape. The laboratory analysis by X-ray diffraction revealed that the plaster mainly consisted of calcium (calcite) and magnesium (dolomite) carbonate, but indicated that it also contained some quartz sand and feldspars. The plaster on the triumphal arch appears somewhat rougher, made with thicker sand, as well as less solid. The horizontal boundaries between different giornate, approximately one metre apart, can be felt by touch. For example, on the northern wall, a border can be detected at the level of the Apostles’ knees, while another one can be discerned above their heads. Nevertheless, the artist apparently refreshed at least some parts of the painting surface with a single layer of limewash, as evidenced by the cross-sections of several samples (figs. 1–2) and the chemical analyses of this layer. The limewash was obviously applied on already dry plaster or on a plaster that was not completely dry but had already begun to form a crust of calcium carbonate on its surface – namely, the boundary between the limewash and the plaster is clearly visible, as the calcium hydroxide did not transite between the two layers. In one spot on the eastern wall, a piece of straw is showing through the plaster – perhaps straw was added to the plaster to reinforce it.

The laboratory analyses results proved that the pigments used in this painting were mainly natural earths, iron-oxide pigments, i.e. yellow and red earth, used for the yellow, red (fig. 1) and purple colours. Apart from those, the painter also used cinnabar to brighten the red tones, which is confirmed by the presence of the characteristic element mercury (Hg). As cinnabar is an extremely intense and expensive pigment, it was mixed with red ochre. The blue colour is not azurite, although that could be inferred from the black spots in some areas of the mural, which could reflect chemical changes in the azurite under the influence of sulphur from the atmosphere. At Vrhe, however, the blue colour is a mixture of black (carbon black), red (red earth), and white (lime) pigments, as proven by stratigraphy and laboratory analyses (fig. 2). The pigments’ main binder is lime from the plaster, while in the case of painting on the limewash, the painter also had to mix them with lime water or lime milk before application, as the calcium hydroxide from the whitewash does not have sufficient binding power. Only for the completely dry-applied finishes could a certain organic binder have been used, though this could not be determined by the laboratory analyses methods applied.

At first glance, we could conclude that the Vrhe mural was made using a true al fresco technique, especially because of the relatively good preservation of some of the painted surfaces. It also appears that the paints adhere firmly to the base and do not peel off in layers but rather crumble together with the plaster granules. The plaster itself is also of very high quality and solid, while the boundaries between the giornate can be distinguished, which is characteristic of painting on fresh plaster. However, the cross-sections of the retrieved samples revealed that the mural in question is not a real fresco, as a layer of limewash can be found everywhere under the paint layer (figs. 1–2). Thus, the mural was created using the lime technique in combination with the basic principles characteristic of frescoes. The technical execution of the painting is therefore excellent, as it nevertheless gives the impression of a fresco buono. The selection of pigments – mainly earth and minerals, which the painter bound with lime water or lime milk and applied to fresh limewash – contributes to this. It was not possible to determine whether an organic binder had been used for the final details of the painting. Therefore, the technique itself does not exhibit Italian influences, as this is a principle of painting on lime whitewash, used mainly north of the Alps. However, Italian influences are evident particularly from the design itself: the almond-shaped eyes, the white light layers, and the accentuated shading from light to dark.

No sinopias that may have been painted on the lower plaster layer are visible, as they are covered with a more recent layer. The underdrawing on intonaco is outlined in brick red with a brush about five millimetres thick (fig. 3). In certain places, such as the hands or the inscription bands, it is even possible to notice the painter’s corrections. The diamond-shaped bordures are outlined in the same colour: as their paint layers are no longer preserved, the drawing is clearly visible. The deep incisions and pouncing, used primarily for the halos, head outlines, and crowns of female saints, play an essential role. The halos were decorated with short rays, probably pressed into the plaster with a piece of wood. There are no incisions on the vault.

The modelling started by applying local colours, which the painter used to fill larger areas such as draperies or faces. There are no underpaintings in the true sense of the word. The master applied the colours from light to dark. He used lighter bases, then kept adding increasingly darker tones until he finally drew the dark finishing contours, which mostly followed the underdrawing (fig. 4).

The faces of the male figures feature stronger cheekbones, while all of them have long, narrow, and slightly arched eyebrows. The eyes are large and almond-shaped, but what draws the attention is the unusual way in which they have been shaped, as if the painter had emphasised the double lines: the outer line, outlined with a dark contour, and the inner line, from which the paint has already peeled off. The pupils, obviously painted during the final additions and on an already dry surface, have also fallen off. The figures’ faces are also characterised by pronounced U-shaped creases above their upper lips, while the prophets retain the sinuous lines of their horizontal forehead creases. The carnation – on which the master applied stronger pink, ochre-yellow, or light brown shadows – is light pink, almost white. Such a strong manner of shading gives the figures an almost caricatured look. The order of the paint layers can be gleaned from the corresponding cross-sections of the samples: from the bottom to the top, the base lime whitewash is followed by a layer of slightly lighter white, then by a very thin layer of pink, and finally by a thinner red line that corresponds to the shadows. The same layers were applied to the hands, which come across as spatulate, while the fingers are straight, schematic, and perfectly parallel. The hair was designed on a base layer of paint, on which the painter, using a thin brush, drew individual strands in parallel, flattened lines according to how the hair fell. Interestingly, in the case of the female saints, he attempted to apply volume modelling to the yellow base by using strong white parallel layers in a sinuous line, which is characteristic of Italian Trecento painting.

The colour modelling of the draperies is very poorly preserved. However, it is still possible to discern that the wrinkles in the chosen colour of the garments were applied on a lighter base using a brush about a centimetre thick. The selected cross-sections reveal that the painter first applied a basic light colour locally, to the whitewash. Over it, he spread a darker and much thinner layer of colour belonging to the fold of the garment (fig. 1). Finally, he decorated some of the garments freehanded (without using any stencils) with black embellishments. There are no midtones and depth shadows to be seen, which may be due to poor preservation, though this is even more likely a feature of the old linear style.

The chancel was painted using three different techniques: the murals on the walls were applied on wet plaster, i.e. using the fresco buono technique; the vault was painted using a combined fresco-secco technique; while the ribs were decorated using only the al secco technique.[1]

________________________________________

[1] KOVAČIČ 1984, p. 307; GREGOROVIČ 1993, p. 42; ZIMMERMANN 1996, pp. 195–196.

Vrhe near Slovenj Gradec, Succursal church of St Agnes, Stage 1 (Vrhe near Slovenj Gradec), 2024 (last updated 18. 10. 2024). Corpus picturarum muralium medii aevi, https://corpuspicturarum.zrc-sazu.si/en/poslikava/phase-1-chuch-of-st-agnes-vrhe-pri-slovenj-gradcu/ (9. 7. 2025).

Legal Terms of Use

© 2025 ZRC SAZU UIFS, Corpus picturarum muralium medii aevi

ZRC SAZU

France Stele Institute of Art History

Novi trg 2

1000 Ljubljana

Spodaj seznam podrobno opisuje piškotke, ki se uporabljajo na našem spletnem mestu.

| Cookie | Type | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| _ga | Non-Necessary | 2 years | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. The cookie is used to calculate visitor, session, camapign data and keep track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookies store information anonymously and assigns a randoly generated number to identify unique visitors. |

| _gat | Non-Necessary | 1 minute | Google uses this cookie to distinguish users. |

| _gid | Non-Necessary | 1 day | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. The cookie is used to store information of how visitors use a website and helps in creating an analytics report of how the wbsite is doing. The data collected including the number visitors, the source where they have come from, and the pages viisted in an anonymous form. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | Necessary | 1 year | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-non-necessary | Necessary | 1 year | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Non Necessary". |

| CookieLawInfoConsent | Necessary | 1 year | The cookie is used to store the summary of the consent given for cookie usage. It does not store any personal data. |

| PHPSESSID | session | Time of session | Cookie stores information about the user's session and allow users to keep their entries during the time of visiting the website. |

| pll_language | Necessary | 1 year | This cookie is used to remember any selection a user has made about language. |

| show_preloader_once | Necessary | Session | With this cookie we remember the user's first visit. |

| viewed_cookie_policy | Necessary | 1 year | The cookie is used to store whether or not you have consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |