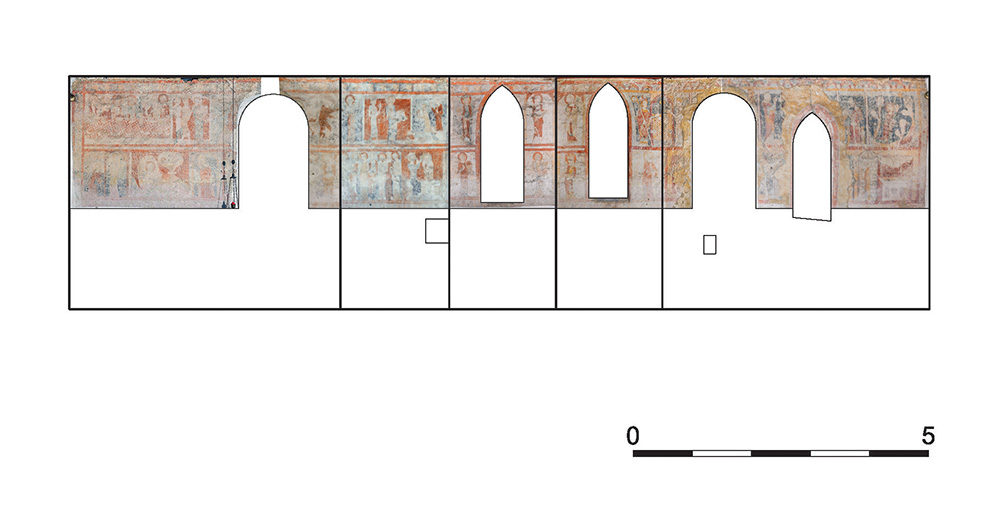

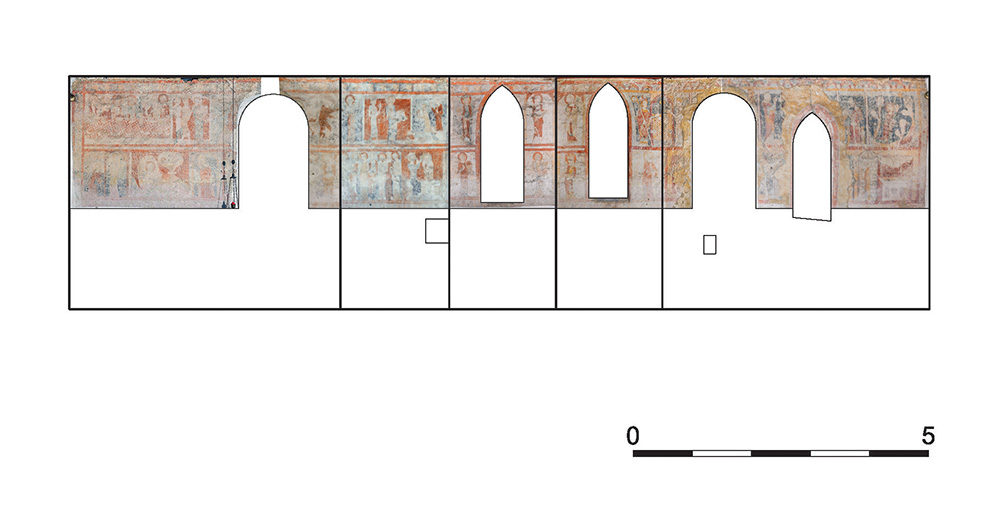

The mural covers the entire surface of the available chancel walls. It is depicted in two bands, starting on the northern wall by the triumphal arch and ending by the triumphal arch wall on the southern side.[1] The depictions include scenes from the lives of the Virgin and Christ and the legends of St John the Evangelist and St John the Baptist.[2] Starting in the upper band, the following scenes follow each other: the Last Supper, the apostle holding a book and explaining the gospel to two heathens or the Conversion of the Philosopher Craton, an unidentified scene, the Arrest of St John the Evangelist, and two related scenes of the Attempted Poisoning of St John the Evangelist.[3] On the eastern wall, two saintly figures are depicted by the window opening: a male figure on the left, sometimes identified as St Oswald and sometimes as St John the Baptist, and St Mary Magdalene on the right.[4] A bishop is portrayed on the south-eastern wall on the left side of the window, while an offering scene, which also extends to the southern wall, is depicted on the right.[5] The upper band of the mural ends here. The first two scenes have been destroyed, the next one remains unidentified, while the final scene portrays St John the Baptist withdrawing into solitude.[6]

In the lower band, again starting on the northern wall, the Annunciation and the Nativity are painted, while the fragmentary scene that follows could be a depiction of the Pentecost or the Coronation of Mary.[7] On the eastern wall, St Dorothy is portrayed to the left of the window, while St Barbara is to the right.[8] St Helena and an unidentified female saint to her right are painted on the south-eastern wall.[9] After two other unpreserved scenes, the cycle is completed by the depictions of St John the Baptist in Herod’s Prison and the Death of St John the Evangelist.[10]

The upper band, beginning on the northern side and ending on the north-eastern wall, depicts scenes from the lives of Christ and St John the Evangelist.[11] The story opens with the Last Supper motif, in which St John the Evangelist lays his head on the chest of Christ, characterised by a cruciform halo.[12] The accepted interpretation is that eight apostles are depicted, making this an abbreviated version of the Last Supper motif.[13] All apostles are painted seated on the same side of the table, covered with a tablecloth adorned with diamond patterns.[14]

Janez Höfler named the following scene “the apostle holding a book and explaining the gospel to two heathens”,[15] while Tanja Zimmermann referred to it as “John the Evangelist explains the gospel to two individuals”.[16] The painting portrays a figure with a halo and an open book, i.e. St John the Evangelist, and two standing figures.[17] Höfler suggests that the depiction could also be interpreted as the Conversion of the Philosopher Craton.[18]

The next scene was destroyed due to the subsequent construction of a window,[19] though France Mesesnel described the partially preserved image when it was uncovered.[20] Allegedly, it included a stylised tree, possibly with a woman sitting in front of it with a child in her arms.[21]

The mural continues with the scene of the saint’s arrest, portraying St John the Evangelist and two soldiers standing next to him.[22] France Mesesnel identified only one soldier in this scene while describing the other individual as a pagan priest with a funnel-shaped headdress, brandishing a sword.[23] On the right side, St John the Evangelist is depicted as a long-haired young man with an open book in his left hand.[24] The background of the scene is blue.[25]

The final, connected scenes portray the saint’s attempted poisoning.[26] In the first scene, the High Priest Aristodemus and St John the Evangelist walk towards the viewer’s right, while the second scene shows only St John the Evangelist in the company of two persons, who are about to witness him reviving the two poisoned criminals who are lying on the ground.[27] With the lower half of its body, the second of the latter figures already transitions into the next scene.[28] France Mesesnel described the figure of Aristodemus in the first scene as a pagan and wrote that St John the Evangelist “resists /…/ all persuasion and hurries towards the right”.

The depictions in the lower band begin with the Annunciation scene next to the triumphal arch.[29] The area features two arcade arches and a pillar, separating the Virgin Mary, portrayed without any attributes, from the kneeling Archangel Gabriel with a book.[30] The painting is followed by the Nativity scene with the manger shaped like a chalice, while Mary and Joseph with a shepherd’s staff and a crown are lying beside it.[31] Joseph is placed in the painted recess at the end of the scene. The lower band continues with nine apostles turned to face each other, while the remaining three were probably destroyed during the construction of the secondary window.[32] Tanja Zimmermann interpreted the scene as the Pentecost, especially because of the cycle’s final scene: the Coronation of Mary.[33] The latter portrays two seated figures: on the left, Christ with a trefoil crown gives blessings. With his right hand, he is touching the crown of Mary on the right, whose hands are folded in prayer.[34]

On the eastern side and the south-eastern wall, both bands of the mural continue with images of male and female saints, as well as other independent motifs, depicted one after another along the two windows.[35] In the upper band, the scenes follow each other from the viewer’s left towards the right, starting at the left window with a figure of a king with a crown and a yellow bowl in his right hand (presumably St Oswald).[36] St Mary Magdalene with a container of ointment is painted to the right of the window, followed by a holy bishop with a staff and a book in his right hand in the next field to the left. To the right of the window is an unidentified offering scene, portraying a bishop and a king by the altar under a canopy with a hanging lantern. On the left, the bishop with a mitre and a staff is placing a bright object on the altar, while the bearded king with a sword is portrayed on the right.[37] In 1942, France Mesesnel wrote that the two figures were both offering “a similar object”, which he described as a round vessel.[38] Regarding this scene, Tanja Zimmermann suggested that it might be a reference to the legend of St Oswald.[39]

In the lower band, the following figures are depicted one after another from left to right: St Dorothy with a basket of flowers; St Barbara (according to Tanja Zimmermann, she is depicted with a tower, while Marijan Zadnikar states that she is portrayed with a chalice); the crowned St Helena with a cross in her hand; and an unidentified female saint.[40]

Somewhat fewer scenes dedicated to the legend of St John the Baptist have been preserved on the southern wall.[41] In the upper band, the first two scenes from the viewer’s left towards the right were completely destroyed by the subsequent addition of the windows.[42] During the uncovering of the mural, France Mesesnel was still able to discern the tip of an alleged wing in the upper part of the mural.[43] To the right of the second window, a standing female figure wearing a red garment with her hands raised in a gesture of supplication has been preserved. She is oriented towards the figure on the left, of which only a hand in the gesture of blessing and a red halo have been preserved.[44] Although the motive remains unidentified, Tanja Zimmermann suggests it was probably a healing scene.[45] In Janez Höfler’s opinion, the destroyed scenes most probably depicted John the Baptist’s birth and childhood until his departure into the desert, which is the only well-preserved scene in this series.[46] It features a dark background with three trees, identified by Marijan Zadnikar as figs. Among them, a kneeling figure with a halo and folded arms, wearing a red garment – i.e. St John the Baptist – looks toward a six-pointed star.[47] France Mesesnel also mentions a poorly preserved bearded figure brandishing a sword, supposedly portrayed in a secluded landscape in front of St John the Baptist.[48]

Like in the southern wall’s upper band, the first two scenes in the lower band have been destroyed beyond recognition.[49] Only France Mesesnel wrote that a hand, hanging over the frame, could be discerned in the first scene, while he recognised two trees in the second scene, painted between the two windows, of which the left was walled up. He also stated that a silhouette of a horse was visible in this spot, just below the lower edge.[50]

However, with the current state of preservation, it is only possible to identify the scene to the right of the second window, which Tanja Zimmermann and Janez Höfler separate into two interconnected scenes, while Marijan Zadnikar treats it as a whole.[51] The first motif is a depiction of St John the Baptist in Herod’s prison. The artist painted a tall brick tower covered with a domed roof. The tower has an open door with a bearded man with crossed arms standing in it.[52] The second and last scene in this series shows the Death of St John the Evangelist or his “self-burial” and a sarcophagus decorated with a rosette and two biforas.[53] Meanwhile, Tanja Zimmermann states that a cloud with God the Father or perhaps an angel carrying the soul of St John the Evangelist is portrayed above the sarcophagus.[54]

Until the window on the south-eastern wall, the two bands are separated by a line outlined in white and red, while from the window onwards, they are separated by a simple red line.[55] The vertical divisions between the individual scenes are marked with white lines, while in the upper band, they are further delimited by a zig-zag border, folded only once on the northern wall and the eastern sides and twice on the southern wall.[56] A similar band also runs along the lower, ground-floor edge of the mural.[57] The window splays are also painted. The window splay on the eastern side is decorated with vines, designed in a slightly more complex manner on the northern than the southern side, while the window splay on the south-eastern wall is adorned with a partially preserved foliated ornament.[58]

________________________________________

[1] ZADNIKAR 1990, p. 18; HÖFLER 2004, p. 144.

[2] ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 50.

[3] MESESNEL 1942, pp. 121–122; ZADNIKAR 1990, pp. 19–22; ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 50; HÖFLER 2004, p. 145.

[4] MESESNEL 1942, p. 122; ZADNIKAR 1990, p. 24; ZIMMERMANN 1996, pp. 50–51; HÖFLER 2004, p. 145.

[5] MESESNEL 1942, p. 122; ZADNIKAR 1990, pp. 24–25; ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 51; HÖFLER 2004, p. 145.

[6] MESESNEL 1942, p. 122; ZADNIKAR 1990, p. 25; ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 51; HÖFLER 2004, p. 146.

[7] MESESNEL 1942, p. 122; ZADNIKAR 1990, pp. 22–23; ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 50; HÖFLER 2004, p. 145.

[8] MESESNEL 1942, p. 122; ZADNIKAR 1990, p. 24; ZIMMERMANN 1996, pp. 50–51; HÖFLER 2004, p. 145.

[9] MESESNEL 1942, p. 122; ZADNIKAR 1990, pp. 24–25; ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 51; HÖFLER 2004, pp. 145–146.

[10] MESESNEL 1942, p. 122; ZADNIKAR 1990, pp. 25–27; ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 51; HÖFLER 2004, p. 146.

[11] ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 50; HÖFLER 2004, p. 145.

[12] MESESNEL 1942, p. 121; ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 50; HÖFLER 2004, p. 145. Mesesnel also states that “a nearby figure is holding a cross”.

[13] ZADNIKAR 1990, p. 19; ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 50; HÖFLER 2004, p. 145.

[14] MESESNEL 1942, p. 121; ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 50.

[15] HÖFLER 2004, p. 145.

[16] ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 50; cf. ZADNIKAR 1990, p. 21.

[17] MESESNEL 1942, p. 121.

[18] HÖFLER 2004, p. 145.

[19] ZADNIKAR 1990, p. 21; ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 50; HÖFLER 2004, p. 145.

[20] MESESNEL 1942, p. 121.

[21] MESESNEL 1942, p. 121.

[22] ZADNIKAR 1990, p. 21; ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 50; HÖFLER 2004, p. 145.

[23] MESESNEL 1942, p. 121.

[24] MESESNEL 1942, p. 121.

[25] MESESNEL 1942, p. 121.

[26] ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 50; HÖFLER 2004, p. 145.

[27] ZADNIKAR 1990, p. 21; ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 50; HÖFLER 2004, p. 145.

[28] MESESNEL 1942, p. 122.

[29] MESESNEL 1942, p. 122; ZADNIKAR 1990, p. 22; ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 50; HÖFLER 2004, p. 145.

[30] ZADNIKAR 1990, p. 22; MENAŠE 1994, p. 245; ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 50; HÖFLER 2004, p. 145.

[31] MESESNEL 1942, p. 122; ZADNIKAR 1990, p. 22; ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 50; HÖFLER 2004, p. 145.

[32] ZADNIKAR 1990, pp. 22–23; HÖFLER 2004, p. 145. MESESNEL 1942, p. 122, described the preserved images of the Apostles as follows: “The standing figure with a halo is turned towards the right, though further on, the image has been destroyed because of the window. After the window, there are two figures with candles (?) in their hands, followed by an entire procession of men and women with halos and books.”

[33] ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 50; HÖFLER 2004, p. 145.

[34] MESESNEL 1942, p. 122; ZADNIKAR 1990, p. 23; ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 50.

[35] HÖFLER 2004, p. 145.

[36] ZADNIKAR 1990, p. 24; ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 50; HÖFLER 2004, p. 146. MESESNEL 1942, p. 122, identified this figure as St John the Evangelist.

[37] MESESNEL 1942, p. 122; ZADNIKAR 1990, p. 24; ZIMMERMANN 1996, pp. 50–51; HÖFLER 2004, p. 146.

[38] MESESNEL 1942, p. 122.

[39] ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 51.

[40] ZADNIKAR 1990, p. 24; ZIMMERMANN 1996, pp. 50–51; HÖFLER 2004, pp. 145–146. Attention must once again be drawn to Mesesnel’s account, as instead of the image of St Dorothy, he identifies St John the Baptist with a chalice and a paten, while describing St Barbara as “a saint with a chalice and a host”; see Mesesnel 1942, p. 122.

[41] HÖFLER 2004, p. 146.

[42] ZADNIKAR 1990, p. 25.

[43] MESESNEL 1942, p. 122.

[44] MESESNEL 1942, p. 122; ZADNIKAR 1990, p. 25.

[45] ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 51.

[46] ZADNIKAR 1990, p. 25; HÖFLER 2004, p. 146.

[47] ZADNIKAR 1990, p. 25.

[48] MESESNEL 1942, p. 122.

[49] ZADNIKAR 1990, p. 25.

[50] MESESNEL 1942, p. 122.

[51] ZADNIKAR 1990, pp. 25–26; ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 51; HÖFLER 2004, p. 146.

[52] ZADNIKAR 1990, p. 26; ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 51; HÖFLER 2004, p. 146.

[53] ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 51; HÖFLER 2004, p. 146.

[54] ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 51; HÖFLER 2004, p. 146.

[55] ZADNIKAR 1990, p. 18.

[56] ZADNIKAR 1990, p. 18; ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 51.

[57] ZADNIKAR 1990, p. 18.

[58] MESESNEL 1942, p. 122; ZADNIKAR 1990, p. 23.

Due to various factors, the mural has not been preserved in its entirety.[1] In its present state, the scenes can be identified mainly by their faded colour surfaces,[2] as the underdrawing has only been preserved in a few places. Parts of the murals were destroyed by the subsequent alterations to the chancel and the creation of the window openings,[3] while the plaster on which they were painted has also contributed to their slightly worse condition, as the lack of lime prevented it from binding enough of the colour pigments, resulting in poorer preservation.[4] Due to the removal of the subsequent limewash, the mural probably also suffered some damage during the uncovering.[5]

________________________________________

[1] JAVORNIK 2008, p. 187.

[2] HÖFLER 2004, p. 144.

[3] ZADNIKAR 1990, p. 17; HÖFLER 2004, pp. 144–145.

[4] KRIŽNAR 2006, p. 199.

[5] ZADNIKAR 1990, p. 18; HÖFLER 2004, p. 144.

The mural in the Muta rotunda is painted in the High Gothic linear style.[1] Together with the oldest layer of frescoes in Crngrob and in the church of St John the Baptist by Lake Bohinj, it belongs to the group of the oldest Gothic murals in Slovenia, though it is considered the most recent of them.[2] Two painters were at work in the rotunda: an older master, also known as the more conservative painter, worked on the northern wall of the chancel; while a younger painter painted the southern wall.[3] This resulted in minor stylistic differences,[4] though the murals on the northern and southern walls were nonetheless created simultaneously.[5]

The first stylistic comparisons between the Muta frescoes and works from outside Slovenia were made by Tanja Zimmermann, who compared them to stylistically similar paintings in Austrian Carinthia.[6] She identified most parallels with the mural in the ossuary in Feistritz bei Grades, painted in the middle of the 14th century. The two murals match in terms of figurative elements, sarcophagus design, and the layout of the Last Supper scene. Zimmermann also compared the depiction of the figures with the mural in the chancel of the church of St Nicholas in Gradenegg, created around 1330.

The figures depicted in the chancel of the Muta rotunda are strongly typified, portrayed frontally or turning slightly, with the emphasis on the gesticulation of the hands.[7] Details such as faces and folds of the garments were only added by drawing, as the figures did not include any shading or volume modelling.[8] The figures painted on the southern wall of the chancel stand out a little, as in that case, the S line of the bodies is already emphasised.[9] The scenes differ more in their depiction of the space. On the northern wall, the protagonists are set against a uniformly coloured, spaceless background, with the ground marked only by a brightly coloured area on which the figures are placed. Meanwhile, the mural on the southern wall also includes architectural scenery. This is particularly evident in the Death of St John the Baptist scene, where the sarcophagus is already painted in perspective.[10]

The mural is dominated by bright colours, such as brick red and yellow in contrast with blue. The only difference is that the colours on the southern wall have remained slightly more intense than those on the northern and eastern walls.[11] Although the poor preservation of the murals indicated that they were probably painted using the dry technique,[12] which is less durable, Anabelle Križnar’s examination of the plaster revealed that they had been painted on fresh plaster without any additional limewash.[13] Therefore, in theory, they should be somewhat better preserved.[14] Križnar assumed that the reason for the lack of durability was the structure of the plaster, which did not allow the pigments to remain in a better condition due to its modest lime content.[15]

________________________________________

[1] ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 144; HÖFLER 2004, pp. 144, 146; KRIŽNAR 2006, p. 197. Regarding the Muta murals, the older literature also refers to the “Early Gothic linear-planar drawing style” (STELE 1969, pp. 85, 134; STELE 1972, pp. 9–10) and the “linear-planar Early Gothic style” (ZADNIKAR 1990, p. 29).

[2] KRIŽNAR 2006, p. 62.

[3] Najnovejša odkritja 1940, p. 8; ZADNIKAR 1990, p. 28; ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 51; HÖFLER 2004, p. 146.

[4] ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 51.

[5] MESESNEL 1942, p. 123; ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 51.

[6] ZIMMERMANN 1996, pp. 52–53.

[7] ZADNIKAR 1990, p. 28.

[8] ZADNIKAR 1990, p. 28.

[9] ZADNIKAR 1990, p. 28.

[10] ZIMMERMANN 1996, pp. 51, 82.

[11] ZADNIKAR 1990, p. 28; ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 51.

[12] ZADNIKAR 1990, p. 25; MENAŠE 1994, p. 245; HÖFLER 2004, p. 144.

[13] KRIŽNAR 2006, p. 199.

[14] KRIŽNAR 2006, p. 199.

[15] KRIŽNAR 2006, p. 199.

Although the dating of the mural varies somewhat in the relevant literature, its origins have been traced to the first half of the 14th century.[1] It was most probably painted between 1330 and 1340.[2]

________________________________________

[1] Cf. MESESNEL 1942, pp. 122–123; STELE 1969, pp. 85, 341; STELE 1972, p. 28; ZADNIKAR 1990, p. 31; MENAŠE 1994, p. 245.

[2] ZIMMERMANN 1996, pp. 49, 53; HÖFLER 2004, pp. 146, 262.

Tanja Zimmermann believes that some of the Spodnja Muta Gothic murals were created by the same master who also painted the southern wall of the parish church of St Nicholas in Gradenegg.[1] The latter apparently worked in Carinthia and was familiar with the templates also appearing in the subsequent murals in Feistritz bei Grades.[2]

________________________________________

The first detailed iconographic analysis of the Muta frescoes was carried out as part of Marjetica Simoniti’s diploma thesis in 1960,[1] while later, writers contributed their own interpretations of certain scenes. Thus, according to France Stele, the murals exhibit clear parallels between the scenes from the life of Christ and the lives of St John the Evangelist and St John the Baptist,[2] which Tanja Zimmermann also detected to a certain extent.[3] France Stele determined that the Muta mural with the scenes from the saintly legends represented the oldest and most extensive cycle of its kind in the territory of today’s Slovenia.[4] He also focused on the Nativity motif, where the manger is replaced by a chalice and Jesus is therefore presented as a Eucharistic gift.[5] He associated this manner of depicting the Nativity, which is considered an iconographic peculiarity, with French artistic models.[6] Meanwhile, Lev Menaše underlined the origin of the manner in which the Annunciation was depicted.[7] He pointed out the kneeling motif, whose origins can be traced back to the customs of the knights and which can be seen in the Muta frescoes in the scene portraying Archangel Gabriel kneeling in front of the standing Virgin Mary.[8] The same author also highlighted the Muta Coronation of Mary scene, stating that it was one of the three ways of depicting this scene.[9] In the latter, Christ is placing a crown on Mary’s head while simultaneously blessing her.[10]

________________________________________

[1] Gl. SIMONITI 1960; ZIMMERMANN 1996, pp. 51–52.

[2] STELE 1972, p. 28; ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 50.

[3] ZIMMERMANN 1996, p. 51.

[4] STELE 1969, p. 85.

[5] STELE 1969, pp. 85–86.

[6] STELE 1969, pp. 85–86; STELE 1972, p. 28.

[7] MENAŠE 1994, p. 245.

[8] MENAŠE 1994, p. 245.

[9] MENAŠE 1994, p. 279.

[10] MENAŠE 1994, p. 279.

As for the initiatives to paint the mural, it should be noted that this part of the Drava Valley belonged to the province of Carinthia, while the rotunda was, according to the known information, maintained by the Augustinian Eremites, who also had connections with the monastery in Völkermarkt. The Augustinians may have also commissioned the adaptation of the rotunda at the end of the 13th or the beginning of the 14th century as well as the murals.

Pigments: white lime, yellow and red earth pigments, carbon black, lead white (?)

Analytical techniques: OM, SEM-EDX, XRD, FTIR

The mural appears to have been painted on two layers of plaster, with the top layer being very thin (only about 2 mm). It is not possible to determine the exact thickness of the lower layer, but it is evidently coarser in texture and unpolished so that the upper layer also adhered to it better. The upper plaster is of a slightly lighter colour than the lower layer. In some places, the two layers adhere well, but in others, the upper layer is peeling away. The plaster is generally very brittle and crumbles easily. Compared to the plasters of other Slovenian Gothic murals, it is quite dark and of brownish-yellow colour. The cross-sections reveal a high sand content with little lime. Another feature that stands out is the very diverse sand granulation, varying from exceedingly fine to large grains, which also affects the overall strength of the plaster (figs. 1–2). X-ray diffraction analyses of the two plaster layers showed the same composition, with calcite, dolomite, and quartz sand predominating in both. The upper layer also contains magnesite (indicating a slightly higher percentage of lime relative to sand than the lower layer) and chlorine, whose presence is probably due to chloride salts rising up the wall with capillary moisture. The lime and the sand are not always well mixed, as in some cases, lumps of lime remain in the plaster.

The pigments are mostly alumosilicates and iron oxides, yellow earth, and red earth, as already suggested by the very choice of colours and their hues. The analyses showed the presence of elements characteristic of these pigments (Fe, Si, Mg, Al). In contrast, the light purple colour sample reveals a mixture of black charcoal, red iron oxide colour, and white lime pigment, which dominates and gives the colour its bright hue (fig. 2). The analyses of one of the samples (the pink colour – fig. 1) also revealed the presence of lead; perhaps the painter added lead white to the earth pigment. Lead was not found in any of the other samples, which, however, does not rule out its presence where no sampling has been carried out. The blue colour does not contain azurite: the results of the analyses only show a high presence of CaCO3 and silicates. It is therefore a mixture of a particular earth pigment with white lime, creating the appearance of blue. What is surprising in all the samples analysed is the presence of gypsum. However, it only appears as a surface layer over the pigment itself, not as a painting base. Gypsum as a preparatory layer has not even been found in the cross-sections. It seems to be a consequence of the sulphatisation process, during which lime transforms into gypsum due to the harmful elements in the atmosphere. The SEM-EDX results indicated extensive biological activity on the surface of the murals (fig. 3), which has not been precisely identified but affects both the preservation of the paintings and the results of the analyses: in some places, the latter are unclear precisely due to the almost uninterrupted surface created by the organisms. Lime from the plaster is the main binder for the pigments, which were probably also impregnated with lime water before application. The paint layers are rather glaze-like and thus do not reveal the use of an organic binder.

The fact that the murals – also damaged when the windows were added subsequently – are faded and poorly preserved leads to the opinion that they were painted using a dry technique. Nevertheless, a detailed technical examination shows that the painter conceived his work as a fresh plaster painting, which can be deduced from the two layers of plaster and the choice of earth colours that are durable in the al fresco technique. This is also proven by the analyses themselves. Even with the naked eye, it is obvious that the colours, which are falling off together with the plaster fragments, were applied directly on the intonaco without any limewash or prior wall preparation. Their poor preservation is probably due to the brittle plaster, which does not contain enough lime to bind the pigments well enough. Moreover, the intonaco is extremely thin and probably applied in extensive giornate (the boundary between them is not distinguishable). As such, it dried too quickly and thus failed to provide enough binding power for the paints applied to it. Therefore, the latter do not adhere well to the base and can be smudged. The cross-sections (figs. 1–2) also indicate that the colours were applied directly to the plaster, while in some places, the boundary between the paint layer and the painting base is surprisingly well defined. Calcium carbonate wraping the pigment grains, characteristic of the al fresco technique, cannot be observed. In these areas, the thin plaster must have started to dry before the painting began. In some places, an extremely thin translucent layer between the plaster and the paint layer can be observed; perhaps some parts of the plaster were refreshed with a thin layer of limewash, after all. As the potential final modelling has not been preserved, it is also impossible to know whether the painting was completed al secco.

There is no detectable sinopia, and no incisions or pouncing have been applied to the mural. The underdrawing is made in red and ochre-yellow colour. The painter used the former for the lines of the bordures or the colour bands that separate the scenes from each other and the latter to draw the figures. The underdrawing is still clearly visible in the last scene on the southern wall next to the triumphal arch, where the sketch made with a brush about three millimetres thick can be clearly seen under the final brown outline (fig. 4).

The modelling is based on local tones in blue, red, yellow, and green, but there is no underpainting as a base for another pigment. As the murals are in a rather poor and faded condition, the colour design can no longer be assessed. While modelling, the painter took advantage of the whiteness of the plaster on which he was painting. Most of the faces are preserved only as white surfaces. The painter drew the contours in brown. The slightly arched eyebrows that span the width of the entire face are quite characteristic. Accordingly, the eyes are very large as well, while the nose is drawn with two parallel lines and broadly spaced en face nostrils, while on the three-quarter profiles, the primary line continues forward to the nostril in a simple, schematic manner. Judging from the related murals at Vrzdenec near Horjul, the carnations in Muta may also have been white and with prominent red circles on the cheeks.

In the case of some of the long-haired figures, bright, markedly wavy, almost zigzag strands of hair, made in single strokes, are still discernible. However, for the most part, only the yellow, brown, and light grey base tones have been preserved. The large clumsy hands with long narrow fingers have also lost their modelling. The drapery is designed simply and schematically, with black lines drawn on the basic hue, while finer colour modelling probably never existed. The figures are completed with a brown outline, which has fallen off in some places. There are no motifs calling for the use of stencils.

Marijan Zadnikar pointed to the Golden Legend as the textual basis for the creation of the Muta fresco.[1] He also underlined a fragment of a 14th-century Gothic stained glass window, preserved in the Muta church, which used to depict a bishop standing under a baldachin and was, according to Zadnikar, intended to thematically complement the frescoes.[2] France Stele assumed that the stained glass window must have been created at the same time as the chancel mural.[3] Although the stained glass fragment disappeared during World War II, it is nevertheless significant, as Stele lists it as one of the few known examples of Gothic stained glass windows in the territory of today’s Slovenia.[4]

________________________________________

[1] ZADNIKAR 1990, p. 28.

[2] ZADNIKAR 1990, p. 17. For a photograph of the stained glass window, see PESKAR 2014, p. 120.

[3] STELE 1969, p. 341.

[4] STELE 1969, pp. 339–340. For iconographic peculiarities, see the Iconographic Analysis section.

Muta, Succursal church of St John the Baptist, Stage 1 (Muta, succursal church of St John the Baptist), 2024 (last updated 29. 8. 2024). Corpus picturarum muralium medii aevi, https://corpuspicturarum.zrc-sazu.si/en/poslikava/phase-1-church-of-st-john-the-baptist/ (24. 5. 2025).

Legal Terms of Use

© 2025 ZRC SAZU UIFS, Corpus picturarum muralium medii aevi

ZRC SAZU

France Stele Institute of Art History

Novi trg 2

1000 Ljubljana

Spodaj seznam podrobno opisuje piškotke, ki se uporabljajo na našem spletnem mestu.

| Cookie | Type | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| _ga | Non-Necessary | 2 years | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. The cookie is used to calculate visitor, session, camapign data and keep track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookies store information anonymously and assigns a randoly generated number to identify unique visitors. |

| _gat | Non-Necessary | 1 minute | Google uses this cookie to distinguish users. |

| _gid | Non-Necessary | 1 day | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. The cookie is used to store information of how visitors use a website and helps in creating an analytics report of how the wbsite is doing. The data collected including the number visitors, the source where they have come from, and the pages viisted in an anonymous form. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | Necessary | 1 year | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-non-necessary | Necessary | 1 year | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Non Necessary". |

| CookieLawInfoConsent | Necessary | 1 year | The cookie is used to store the summary of the consent given for cookie usage. It does not store any personal data. |

| PHPSESSID | session | Time of session | Cookie stores information about the user's session and allow users to keep their entries during the time of visiting the website. |

| pll_language | Necessary | 1 year | This cookie is used to remember any selection a user has made about language. |

| show_preloader_once | Necessary | Session | With this cookie we remember the user's first visit. |

| viewed_cookie_policy | Necessary | 1 year | The cookie is used to store whether or not you have consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |