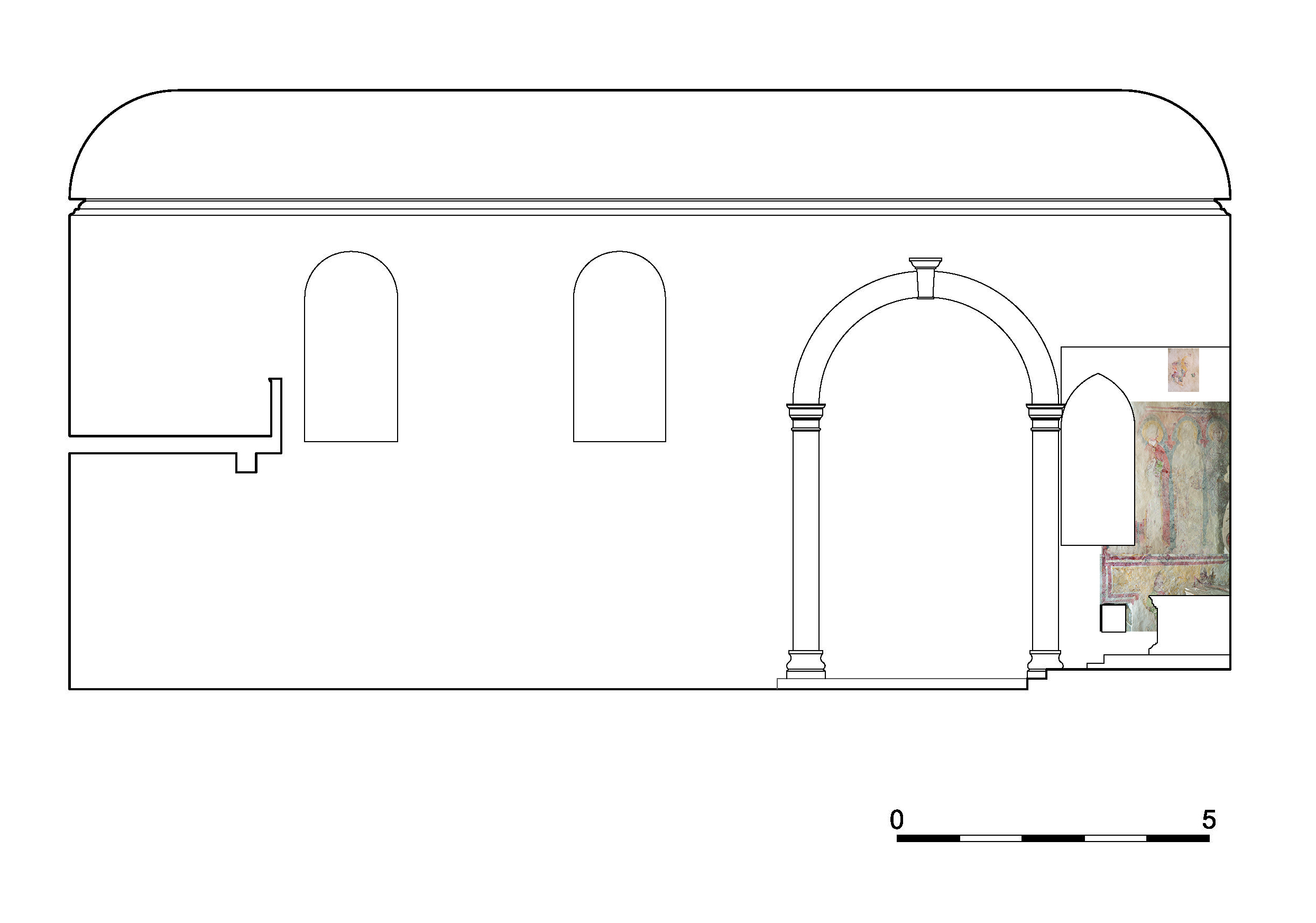

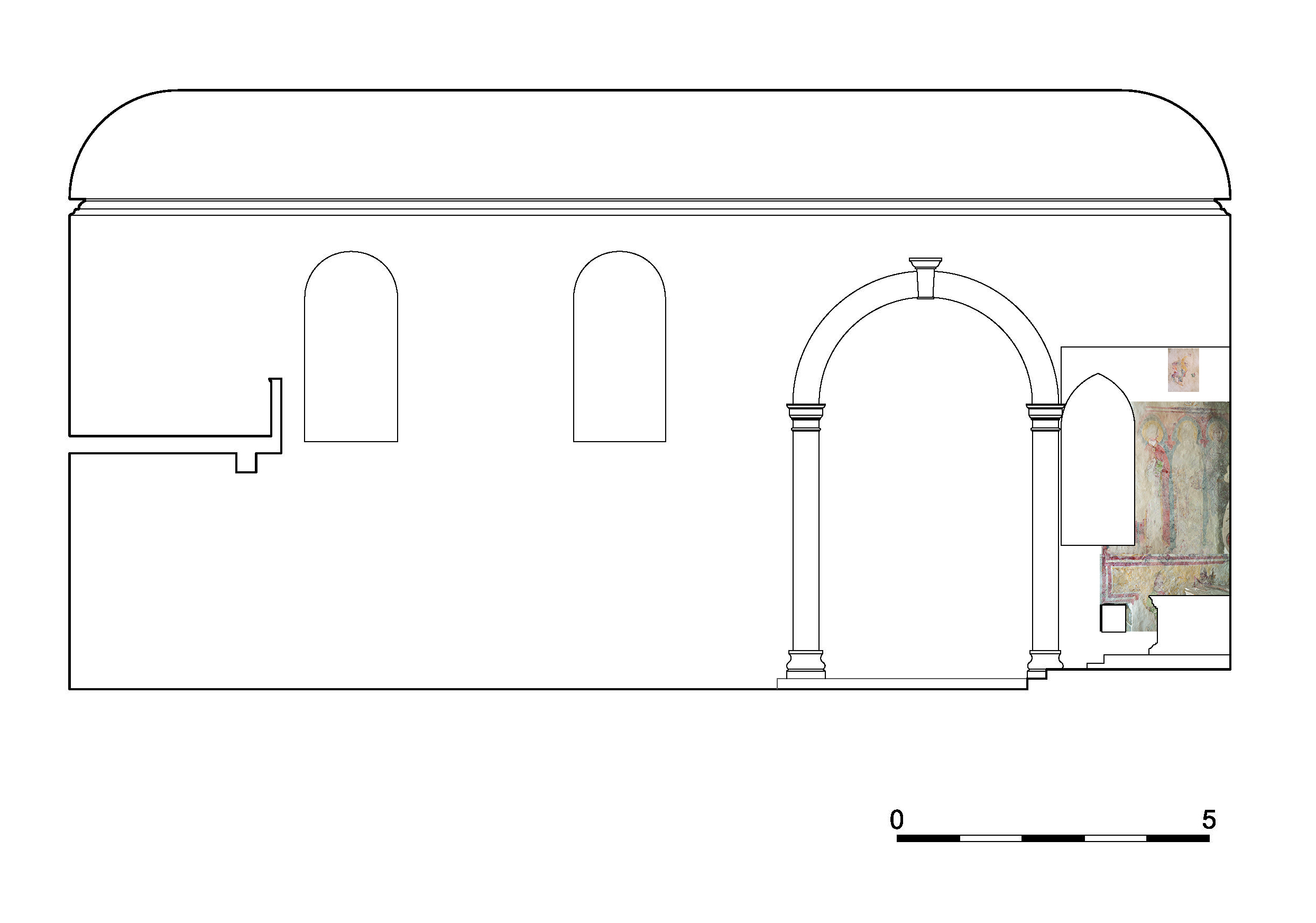

The painting in the corner between the northern nave wall and the triumphal arch is organised in three bands. The lower and middle bands are separated by a simple border consisting of colour stripes (red, white), while the middle and upper bands are divided by a border consisting of stripes and a vegetal pattern (in white, yellow, and red). The painting extended over the entire height of the medieval nave wall. In the lower band, the head of St George and a figure of the princess (down to her waist) in a three-quarter turn from a preserved fragment of the scene depicting St George on horseback fighting the dragon with the princess nearby are visible. The figure of the princess is preserved down to her waist. She is wearing a dress, whose left half is green while the right half is red, with a collar closed to the neck.[1] In the middle band, free-standing figures of saints and bishops are centrally placed in Gothic niches. Due to their poor preservation, the figures’ identity is not clear. A fragmentary inscription in Gothic script, stating MARCVS, can only be made out above the third figure, shedding light on the saint’s name. The images of saints and bishops continued on the triumphal arch as well. Today, only a fragment of a bishop’s figure in a pointed niche is visible, while the Baroque altar of St Catherine obscures the continuation. The upper band of murals on both walls is very poorly preserved. It might have depicted the scenes from a hagiographical cycle (perhaps St Michael or St Catherine), although it seems that here, just like in the middle band, figures of saints and bishops were depicted in niches. This is suggested by the architectural frame of the niche, located to the left of the head of the rightmost figure on the northern wall and identical to the niches in which the figures in the middle band are placed.

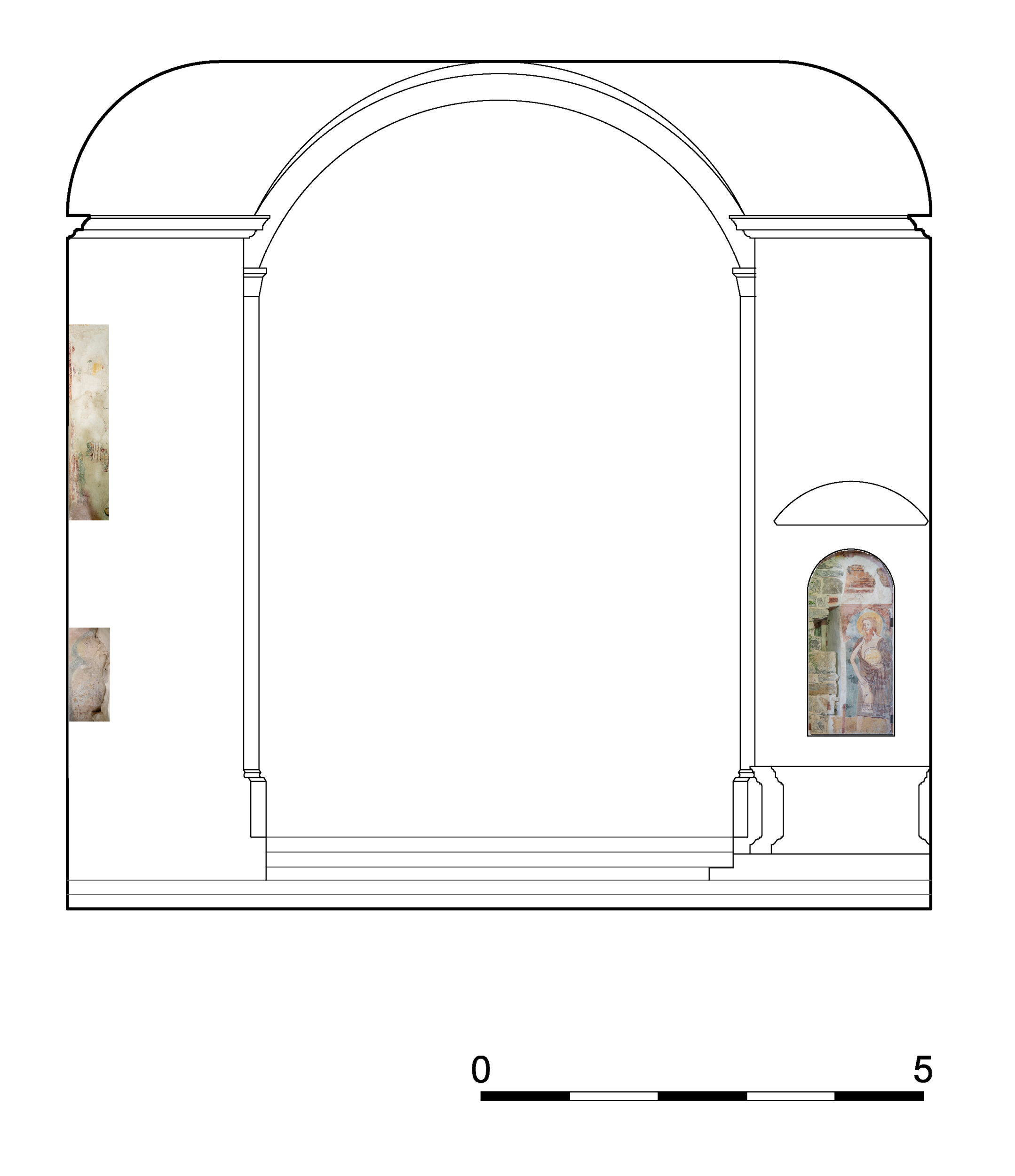

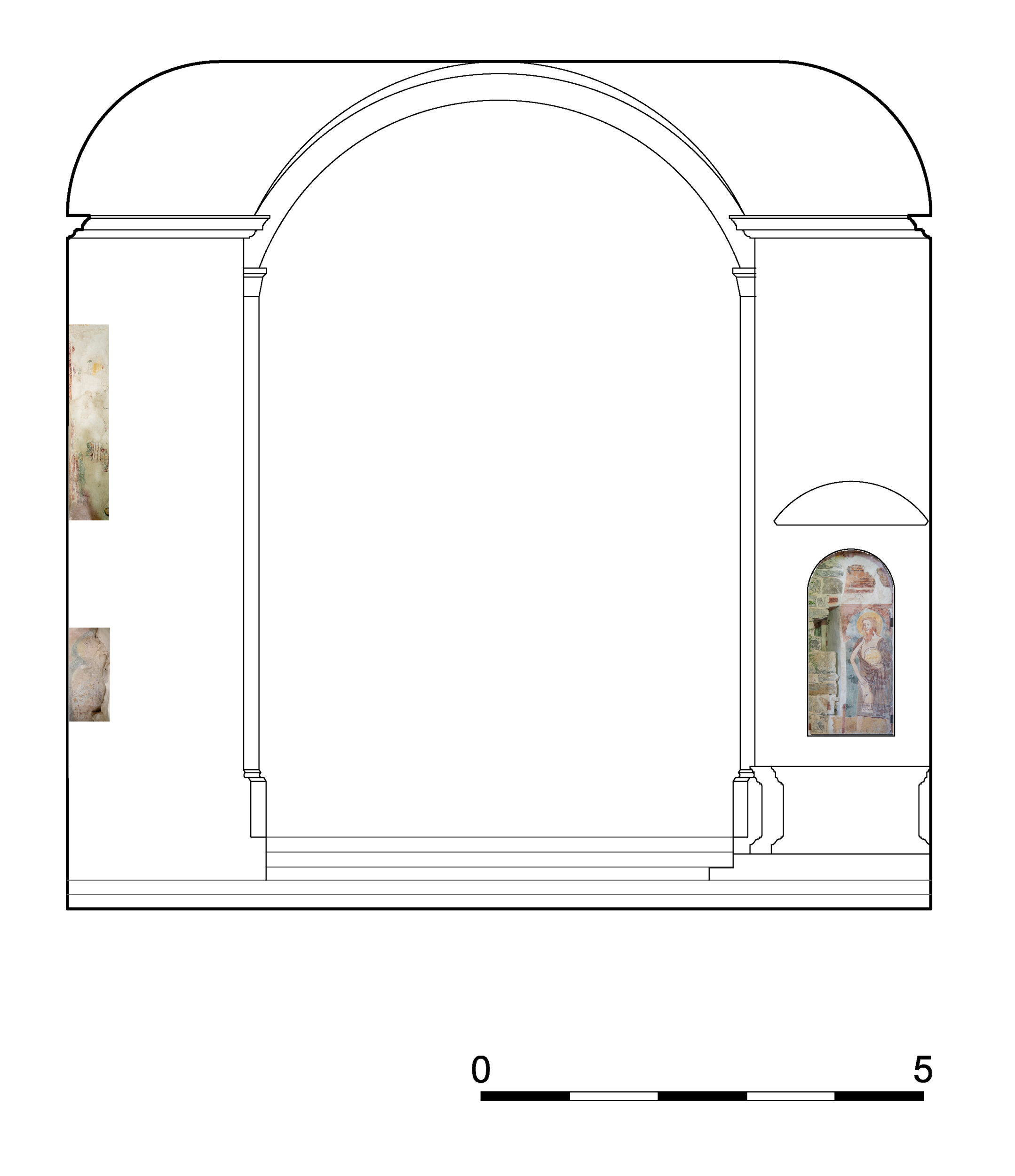

The figure of St John the Baptist has been preserved on the southern part of the triumphal arch. The saint is depicted in a three-quarter profile in a pointed Gothic niche, identical to those on the northern nave wall and the northern part of the triumphal arch. He has long brown hair, a scruffy beard, and wears a brown cloakthat only covers his shoulders in the upper part of his body and then falls in folds from the waist down. In his left hand, he holds a disc depicting a lamb, while in his right, he holds an unrolled scroll with a partially visible canonical inscription [ECC]E / [AGNU]S / DE[I] / Q[UI TOLLIT PE]CHATA / MUN / DI.

________________________________________

[1] For an analysis of the type of clothing that the princess is wearing, see TURK 2022.

The fragments in the corner between the northern nave wall and the triumphal arch are in very poor condition, while the figure of St John the Baptist behind the side altar on the southern part of the triumphal arch is better preserved.

The uncovered frescoes largely reflect the stylistic characteristics of the Gothic linear style. They are characterised by the strong dark red line that completely defines the figures, their bodies, and their facial features, outlining them and giving them substance, while the colour is of secondary importance. The positioning of the figures is static. The full-body frontal or three-quarter profile images do not communicate with each other, there are no facial expressions, the figures are depicted individually on a flat monochrome background, and their arms and legs are not in the correct proportion to the rest of their bodies.[1] The murals are characterised by a simple colouring consisting of earth pigments (red, green, and yellow ochre) and lead white as well as flat monochrome planes (surfaces) and saintly halos, while the individual bands are separated by simple borders consisting of multicolour stripes. These features suggest that some elements of the Romanesque tradition still remain, which can also be seen in the red cheeks of St George and the princess. In some places, the decoration of the individual details with lead white pearls is still visible.[2] Many examples of paintings in the linear Gothic style have been preserved in South Tyrol,[3] while certain stylistic features can also be identified in the nearby region of Friuli,[4] where the façade and oratory of the Church of St George in Rualis near Cividale show many remarkable similarities with the Biljana murals.[5]

If we compare John the Baptist from the Church of St Michael in Biljana with Jesus Christ from the Second Temptation of Christ scene of the southern wall of the oratory in Rualis, we see that the two figures are almost identical. Both are full-body images, depicted in a three-quarter profile, with the same rotation, their left arms bent next to their bodies. While John the Baptist’s right arm is lowered because he is holding a scroll, Christ’s right arm is raised, pointing at the devil. Analogies can be found in the shape of their facial features (the line defining the nose continues into the eyebrow, the slightly elongated arch of the other eyebrow is drawn in a single stroke in both cases, the shape of the eyes suggests eyelids and under-eye bags, the figures share the same shape of the lips, the chin contour continues directly from the scalp) as well as their clothing (just like Christ’s outer garment, John the Baptist’s cloak covers his left shoulder and left arm, falling freely to waist height, so that the right arm emerges from underneath while the cloak also covers the right shoulder). Obvious similarities can also be found if we compare the facial features of St George or the saint in the upper band of the Biljana church murals and the head of one of the apostles in the Last Supper scene in Rualis – namely, the shape of the nose, eyebrows, eyes, the same curved lip lines, and hairstyle. The same is true of the figures portrayed frontally: if we compare the only partially preserved face of one of the bishops on the northern wall in Biljana with the face of one of the angels on the southern wall of the oratory in Rualis or the face of St Nicholas on the façade of the church in Rualis, similarities emerge in the almond-shaped eyes, the line indicating the eyelids and the under-eye bags, the curved lips, and the nose, outlined only at the point of the nostrils. Both bishops also share the same mitre and vestment design, although these details are very poorly preserved in Biljana. The murals at both locations are characterised by the same colour scheme and large monochrome planes that form the background. The simple borders with lines in the red and white combination and the intermediate border with the vegetal pattern are repeated. Unfortunately, only a fragment of the border with the vegetal motif has been preserved in Biljana, but if we compare it with the much better-preserved border on the southern wall in Rualis, we realise it is the same motif, with the border in Rualis merely continuing in a different colour. If we compare the figures even more closely, we can also notice the same shape of the ears, indicated by a single line spiralling inwards at the top and the bottom. Another important detail is a small preserved fragment of the lower band of the painting on the eastern wall of the oratory in Rualis (in the right corner below the First Temptation of Christ), depicting a figure of a male or female saint

in a niche, whose design appears to be identical to the niches with saints and bishops in the Church of St Michael in Biljana. Given the poor preservation of the Rualis fragment, the cross-shaped capital, whose red outer colour outlines the inner oval in a darker shade, is crucial for the comparison. Based on these similarities, the oldest layer of paintings found in Biljana can be attributed to the same master who painted the façade of the church and oratory in Rualis.

________________________________________

[1] This is most evident in the only figure that is almost completely preserved – St John the Baptist on the southern part of the triumphal arch.

[2] Especially on the princess’s collar on the northern wall and on the pointed arch under which St John the Baptist stands on the southern part of the triumphal arch.

[3] Especially at the following locations: Bolzano/Bozen, Bressanone/Brixen, Novacella/Neustift, Cornedo all’Isarco/Karneid, Scena/Schenna, Merano/Meran; cf. Waltraud KOFLER ENGL, Frühgotische Wandmalerei in Tirol. Stilgeschichtliche Untersuchung zur “Linearität” in der Wandmalerei von 1260–1360, Bozen 1995, pp. 27–45.

[4] For example, strong outlines and flat colour planes define the murals in the northern transept of the Basilica of Aquileia (see Rachele NARDINI, Affreschi di epoca gotica nella basilica di Aquileia, Antichità altoadriatiche, 69/2, 2010, pp. 521–543), the late 13th-century scene of Mary on the throne with the child and four saints in the Church of St Martin in Terzo d’Aquileia (see Giuseppe FRANCESCHIN, La chiesa di San Martino a Terzo di Aquileia, Udine 2015), and especially the murals in the Church of St Pantaleon in Rualis near Cividale and on the façade and in the oratory of the Church of St George in Rualis (see Cristina VESCUL, Le pitture murali secoli XIII–XV. La chiesa di San Giordio in Vado a Rualis, Udine 2010, pp. 39–80).

[5] Cristina VESCUL, Le pitture murali secoli XIII–XV. La chiesa di San Giordio in Vado a Rualis, Udine 2010, pp. 39–80.

The analysis of iconographic elements, clothing culture, and stylistic comparisons of the Biljana murals points to the early 14th century. The murals were probably painted in a similar period to those on the façade and in the oratory of the Church of St George in Rualis. Thus, they could be dated to the second or perhaps the beginning of the third decade of the 14th century.

The murals can be attributed to the master who also painted the oratory and façade of the Church of St George in Rualis near Cividale. The northern stylistic character of the murals with the elements of the Romanesque tradition, the Italian-influenced clothing culture, certain iconographic solutions, and modest quality suggest that this could be a work of a local master.

The head of St George and the figure of the princess from the preserved fragment of the St George fighting the dragon scene are visible in the lower band.[1] The iconographic scene is mainly recognisable from the triangular white shield that St George holds in his right hand and the spear in his raised left hand, which he is probably using to pierce the dragon that is not visible. In the middle band, fragmentarily preserved free-standing figures of saints and bishops are centrally placed in Gothic niches. Due to the poor state of preservation, their identification is not possible – except in the case of the third figure, above which the Gothic inscription MARCVS has been preserved. The images of saints and bishops continued on the triumphal arch as well. Today, only a fragment of a bishop’s figure in a poined niche is visible, while the Baroque altar of St Catherine obscures the continuation. The upper band of murals on both walls is very poorly preserved. It might have depicted the scenes from a hagiographical cycle (perhaps St Michael or St Catherine), although it seems that here, just like in the middle band, figures of saints and bishops were depicted in niches. This is suggested by the architectural frame of the niche, located to the left of the head of the rightmost figure on the northern wall and identical to the niches in which the figures in the middle band are placed. The Gothic vaults themselves place the murals in a specific time frame, even though the arrangement is typologically traditional. Similar arrangements of figures under Gothic vaults can also be found in the Church of St Magdalena in Bolzano from around 1330[2] and in the Church of St Cecilia in Chizzola in Trentino from the second decade of the 14th century.[3] An example of this type of setup from around 1325, located in the more immediate vicinity, is the mural in the northern transept of the Basilica of Aquileia,[4] while saintly figures in pointed vaulted niches were also painted by Giotto at the beginning of the century in the chapterhouse of the Basilica of St Anthony of Padua in Padua.[5]

St John the Baptist has been preserved on the southern part of the triumphal arch. He is holding a disc with the depiction of a lamb in his left hand and an unrolled scroll with the canonical inscription [ECC]E / [AGNU]S / DE[I ]/ Q[UI TOLLIT PE]CHATA / MUN / DI in his right hand. The iconographic motif of John the Baptist with a disc depicting a lamb was quite common in the second and third decades of the 14th century in nearby Friuli. For instance in the Chapel of St Nicholas in the Udine Cathedral[6] and the Church of St Maurus in Rive d’Arcano,[7] while as many as two such examples can be found in Aquileia: in the left transept of the Basilica of Aquileia[8] and the so-called Chiesa dei Pagani between the Basilica and the Baptistery.[9] The same iconographic motif can also be noted in the illuminated manuscripts from Avignon on a parchment document of 1333, kept in the Multscher Museum in Vipiteno/Sterzing in South Tyrol.[10]

________________________________________

[1] For the iconography of St George, cf. Otto VON TAUBE, Zur Ikonographie St. Georgs in der italienischen Kunst, Münchner Jahrbuch der bildenden Kunst, 6, 1911, pp. 186–203; Sigrid BRAUNFELS, Georg, Lexikon der christlichen Ikonographie. Ikonographie der Heiligen (ed. Engelbert Kirschbaum), 6, Rom-Freiburg-Basel-Wien 1974, coll. 365–390; George KAFTAL, Fabio BISOGNI, Iconography of the Saints in the Painting of North East Italy, 1, Florence 1978, coll. 347–374.

[2] Waltraud KOFLER ENGL, Il gotico lineare, Trecento. Pittori gotici a Bolzano (edd. Andrea de Marchi, Tiziana Franco, Silvia Spada Pintarelli), Bolzano 2000, pp. 27–45, p. 28.

[3] More about the fresco cycle in Chizzoli Ezio CHINI, Il Gotico in Trentino. La pittura di tema religioso dal primo Trecento al tardo Quattrocento, Le vie del Gotico. Il Trentino fra Trecento e Quattrocento (edd. Laura dal Prà, Ezio Chini, Marina Botteri Ottaviani), Trento 2002, pp. 83–87.

[4] Cf. Rachele NARDINI, Affreschi di epoca gotica nella basilica di Aquileia, Antichità altoadriatiche, 69/2, 2010, pp. 526–527.

[5] Cf. especially Luca BAGGIO, Un capolavoro da riscoprire. Gli affreschi di Giotto nella Sala del Capitolo al Santo, Padova e il suo territorio, 31/180, 2016, pp. 6–9; Luca BAGGIO, Giotto e il rinnovamento dell’iconografia antoniana nel Capitolo del Santo, Bollettino del Museo Civico di Padova, 100, 2011, pp. 41–58, 290–291; Enrica COZZI, Giotto e bottega al Santo. Gli affreschi della Sala Capitolare, dell’andito e delle cappelle radiali, Cultura, arte e committenza nella basilica di S. Antonio di Padova nel Trecento (eds. Luca Baggio, Michela Benetazzo), Padova 2003, pp. 77–91.

[6] See QUINZI 1999, p. 10.

[7] Cf. Paolo CASADIO, Rive d’Arcano Chiesa di S. Mauro, La tutela dei beni culturali e ambientali nel Friuli Venezia Giulia 1986–1987, Trieste 1991, pp. 271–272.

[8] Cf. Sara TURK, Affreschi trecenteschi previtaleschi nel duomo di Udine, Il patriarcato di Aquileia. Identità, liturgia e arte. Secoli V-XV (eds. Zuleika Murat, Paolo Vedovetto=, Roma 2021, pp. 353–373, and earlier bibliography.

[9] Cf. Rachele NARDINI, Affreschi di epoca gotica nella basilica di Aquileia, Antichità altoadriatiche, 69/2, 2010, pp. 524–527.

[10] Cf. Waltraud KOFLER ENGL, Il gotico lineare, Trecento. Pittori gotici a Bolzano (edd. Andrea de Marchi, Tiziana Franco, Silvia Spada Pintarelli), Bolzano 2000, pp. 42–45, cat. 4; Martin ROLAND, Gabriele BARTZ, Illuminierte Urkunden 1333-12-19_Sterzing-Vipiteno, www.monasterium.net/mom/IlluminierteUrkunden/1333-12-19_Sterzing-Vipiteno/charter (17 June 2022).

Pigments: white lime, yellow earth (goethite), red earth (haematite), green pigment (unidentified), carbon black

Analytical techniques: OM, Raman, XRD

The plaster is very hard; it was probably consolidated during the restoration. It consists of lime and sand, which contains oval and angular grains of various colours (fig. 1). Due to the exceedingly small quantities of samples at our disposal, it is not possible to glean much information about the plasters from the cross-sections. Raman spectroscopy only confirmed the presence of calcite, while the XRD technique identified dolomite and, to a lesser extent, quartz in addition to the dominant calcite. A giornata is clearly visible between the lower and upper part of the mural, revealing the progression of the work from top to bottom; the lower plaster overlaps the upper one indicating that it was applied after the upper plaster.

The mural was made using mainly earth pigments, as already suggested by the very choice of colours. The cross-sections indicate the use of inorganic pigments such as white lime, yellow and red earth, some sort of green pigment, and an organic black. Calcite, goethite and haematite, green earth, and carbon black were identified with Raman spectroscopy. There is no blue pigment, and the dark blue background is in fact a mixture of white lime, carbon black, and a bit of red and yellow earth (fig. 2). The primary binder is lime from the plaster, though the pigments may have been impregnated with lime water or lime milk before application. The final details were probably added on an already dry support using an organic binder. Consequently, these parts have mostly fallen off already, as they did not adhere as well to the painting surface as the pigments applied al fresco.

Most of the mural was applied on fresh plaster, al fresco, as indicated by the cross-sections (figs. 1–2) as well as by the good preservation of some of the primary colours. Some parts, such as the faces and additional colour modelling, were probably painted on a dry surface, al secco, so they have already fallen off or are blurred.

Very thin incisions for the red horizontal bordures are noticeable, but there are no pouncings. It was not possible to determine whether the halos and architectural elements were also incised. The underdrawing was probably outlined in pink, which was mostly well covered with layers of colour and a final dark red contour. We can observe that on the right hand of the first preserved full-length figure, on the fingers of the man’s left hand in which he is holding a book, as well as along the red contour just below his collar (fig. 3). The painter applied the basic colour layers with a broad brush, which he also used to create the folds of the draperies. When modelling the faces, the painter used thinner brushes with great precision. He first outlined the facial features and the shape of the beard and jawline in vivid red, over which he then traced the final shape with a dark red contour. The long eyebrows, prominently arched above the eyes, are particularly interesting. The eyes are large and black, narrowing in the corners. The eyelids are subtly indicated with a reddish semi-dry brushstroke. In the case of the three-quarter faces (the figures on the lower part of the wall), a straight nose proceeds from the inner eyebrow, ending in an elongated tip and an almost straight nostril (fig. 4). In the case of en face portrayals (only the saint in the corner has been preserved), the nose is also straight with a long tip and two shorter nostrils. The cheeks are additionally coloured with a red circle. The mouth is fleshy, the upper lip longer and shaped as a double zigzag, while the lower lip is short and separated from the upper lip with a dark red line. Such specific modelling of the faces confirms that the same painter worked on both the upper and lower parts of the wall. With curled ends, the ears are shaped like small pretzels. Hair carried out on an ochre colour base is rich with curls or strands, outlined by the dark red colour of the final contour. The potential light modelling has fallen off. The hands are elegant and feature long fingers, while the hands of the woman in the lower band are tiny and match her thin figure. The carnation is light pink, and the fingers are concluded with a dark red contour (fig. 3). The painter designed the drapery of the full-length saints using broad brushes and often modelled on a white basic layer on which he would trace wide folds. In places, strong final contours have been preserved. The modelling has mostly fallen off, but the remains still suggest that the painter knew how to combine broad and thin brushes for soft modelling and that he painted from light to dark.

Biljana, Parish church of St Michael, Stage 1 (Biljana), 2024 (last updated 29. 8. 2024). Corpus picturarum muralium medii aevi, https://corpuspicturarum.zrc-sazu.si/en/poslikava/phase-1-biljana/ (3. 12. 2025).

Legal Terms of Use

© 2025 ZRC SAZU UIFS, Corpus picturarum muralium medii aevi

ZRC SAZU

France Stele Institute of Art History

Novi trg 2

1000 Ljubljana

Spodaj seznam podrobno opisuje piškotke, ki se uporabljajo na našem spletnem mestu.

| Cookie | Type | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| _ga | Non-Necessary | 2 years | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. The cookie is used to calculate visitor, session, camapign data and keep track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookies store information anonymously and assigns a randoly generated number to identify unique visitors. |

| _gat | Non-Necessary | 1 minute | Google uses this cookie to distinguish users. |

| _gid | Non-Necessary | 1 day | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. The cookie is used to store information of how visitors use a website and helps in creating an analytics report of how the wbsite is doing. The data collected including the number visitors, the source where they have come from, and the pages viisted in an anonymous form. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | Necessary | 1 year | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-non-necessary | Necessary | 1 year | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Non Necessary". |

| CookieLawInfoConsent | Necessary | 1 year | The cookie is used to store the summary of the consent given for cookie usage. It does not store any personal data. |

| PHPSESSID | session | Time of session | Cookie stores information about the user's session and allow users to keep their entries during the time of visiting the website. |

| pll_language | Necessary | 1 year | This cookie is used to remember any selection a user has made about language. |

| show_preloader_once | Necessary | Session | With this cookie we remember the user's first visit. |

| viewed_cookie_policy | Necessary | 1 year | The cookie is used to store whether or not you have consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |